In 2013, I joined what proved to be a great hemorrhage of New Yorkers decamping to Los Angeles in search of the bourgeois-bohemian California dream. (I like to claim that I was among the vanguard of that particular hemorrhage, at least.) Like my fellow transplants, I yearned for adequate space and light so my fiddle-leaf fig could thrive and a cupboard stocked with Heath Ceramics, and LA really came through. Of course, I neglected to close the door behind me, and New Yorkers continued to pour in, driving up our rents and making it impossible to get a walk-in at Speranza, let alone Little Dom’s. The pandemic has only opened the floodgates wider, because those who have the luxury of working from anywhere might as well hunker down somewhere more pleasant. This theoretically applies to me, so I’ve upped the ante by moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico, the oldest and highest capital city in the country, and a place whose charming character is in no danger of being diluted by my SoCal sensibilities. After all, it’s mandated by law.

Santa Fe has long opened its arms to the “creative class” and other lovers of beauty and history—you can probably even name a few—especially after its viability as a trade center was stunted by the rerouting of the railroads in the early 20th century (and the later decommissioning of Route 66) and cultural tourism emerged as a defining industry. Visitors were captivated by the charms of the prevailing adobe architecture, so city planners decided to double down on what set Santa Fe apart, instituting a series of standards in the 1950s to ensure consistency and satisfy tourists’ appetites and expectations, thereby codifying the “Santa Fe style.” Existing structures that fit the bill were protected, but new constructions were also required to be built in the style, and some grand old buildings were radically retrofitted, most notably the previous state capitol. The full story of how this style took shape is a little more complicated, of course, and in examining how this “City Different,” as it calls itself, came to be so, I’ve also discovered some disquieting ways it’s not so different.

Right before I moved here, I’d heard talk about a noticeable influx of Angelenos, which gave me pause. Was I a cliché? A scourge? But when I consulted Google on the phenomenon, I was pleased that the only trend piece I could find was published in 1991, by the AP no less. This led me to believe that I could possibly once again get in on the ground floor of a diaspora, at least in the eyes of the public record. But now that I’m here, I’ve gathered anecdotally that those Santa Feans whose arrival predated mine are already irked by the changing feel of the town, and the newcomers that they hold responsible. This cohort also includes a steady incursion from the east, with wealthy, mostly white Texans swarming over the state line in search of lower property taxes and ample space for their sprawling new constructions (often second or third homes), which is, without doing much research, what I assume Texans like. On the other hand, one might generalize that the affluent, also mostly white Angelenos now flocking to the city crave vintage, original detail, instead of that faux-dobe that others might be content with. Along with all those other authentic touches that are basically a crime to skimp on, even on the McMansion-ified outer margins of town: rough-hewn latillas covering our ceilings and surrounding our properties (called “coyote fencing” in this context); quirky corner fireplaces; nichos to house our objets; and corbels wherever possible.

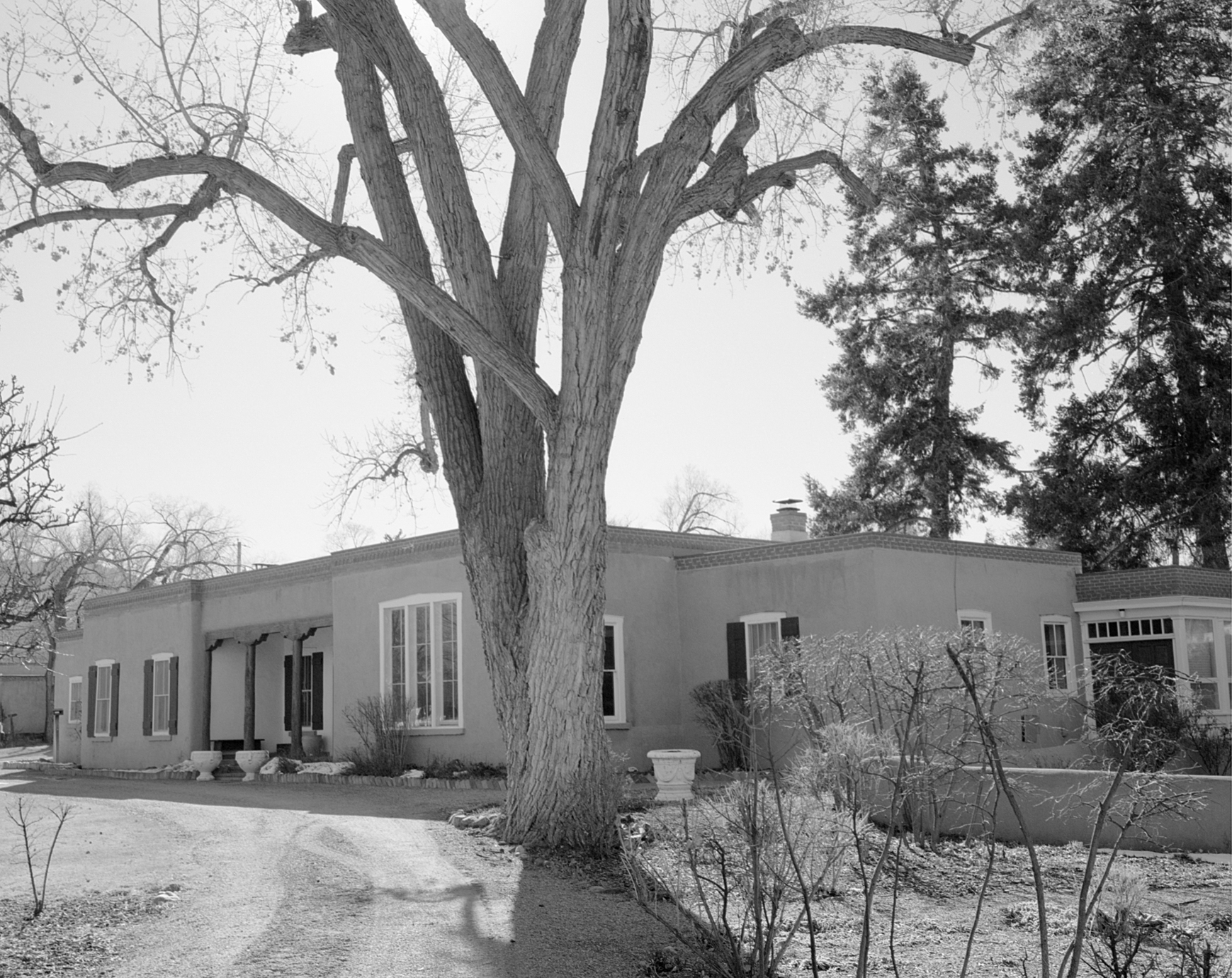

But the terms “original” and “authentic” are often misleading, and Santa Fe style is a useful illustration of why. Essentially, Santa Fe style is both a description and a prescription of the vernacular expressed by local architects and builders, developed from the first pueblos up until 1957, when the style was effectively frozen in time and made law, largely through the efforts of influential local architect John Gaw Meem. This organic accretion of styles is what makes Santa Fe style uniquely difficult to define, but I asked Santa Fe–based architectural historian and storyteller Rachel Preston Prinz to try anyway. She describes it as “a mishmash that includes indigenous architecture, Spanish architecture, Mexican period, and early American period architecture to 1957.” The sedimentary layers of Santa Fe’s architecture reflect the region’s history of successive jurisdictions: the pre-colonial period, the Spanish settlement, the brief interlude of restored indigenous rule after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, Mexican independence in 1821, American conquest 25 years later and New Mexico statehood in 1912. Other styles and innovations, imported from Europe and elsewhere, made their way along the Santa Fe Trail and the eponymous railroad, especially in the years leading up to statehood. But Prinz laments that today’s Santa Fe style is often inaccurately conflated with Spanish Pueblo Revival (the two terms even share a Wikipedia page). While this is what we most often picture when we think of Santa Fe architecture, Territorial Revival really deserves to share top billing with Spanish Pueblo Revival. Because once you find out what the former is, you see it everywhere.

When we moved into our house here, I noticed these little triangular pediments over each window, which I assumed were the lark of some 90s-era renovator because I associated that shape with neoclassicism, seemingly random and postmodern in this context. I fantasized about bringing the house back to its “original glory” by removing them, if we ever had the financial wherewithal to indulge in something so frankly unnecessary. I was also somewhat bummed out by the state capitol building that I was passing multiple times a day, thinking how boringly out of character it seemed. How misguided I was! Cursory research revealed my pediments and the capitol are classic examples of the Territorial style (and its revival). Though it shares many traits with Pueblo architecture (adobe construction, flat roofs), Territorial style emphasizes symmetry and simplicity and usually includes brick copings and the aforementioned neoclassical details that were fashionable during New Mexico’s territorial (pre-statehood) period, in stark contrast to the bulbous asymmetry, setbacks, and heavy wooden ornamentation that defines Spanish Pueblo Revival. I was comforted by the knowledge that neither the capitol nor my pediments were wanton aberrations, and in fact I now regard them fondly.

It’s also enlightening to take a peek at the city code, to see how the bureaucracy has kept up with the times with respect to enforcement of Santa Fe style. The official justification is “to preserve and protect the identity and character of Santa Fe, and enhance the business economy; and promote water conservation and efficiency through preserving natural areas.” It’s no accident that this style of architecture emerged in a drought-prone region with a yearly average of 325 sunny days and wide temperature variation. The thick mud walls, small windows and strategic positioning with respect to the sun made these structures extremely well-suited to the high desert climate. If the environmental sensitivity dovetails with our current (hopefully permanent) focus on sustainability, it’s also just much easier to comply with common- sense energy conservation tactics based on what the original stewards and inhabitants of this land knew long before Europeans arrived.

But no matter how the city’s style is defined, it’s not too surprising that the arbiters of these aesthetic movements have also largely been affluent white transplants, lured to Santa Fe for many of the same reasons tourists and “internal expats” like me flock here today: light, fresh air and that Santa Fe style. It was this ilk who initially saw the economic value of preserving the uniform, unique aesthetic by mostly appropriating indigenous form factors and materials. So the trend continues and reveals one way Santa Fe isn’t unique: the drive to define as “authentic” whatever state the place was in when rich white folks arrived, and to wield money and power to pass and enforce rules, under the guise of preservation, to ensure that some “out-of-scale” affordable housing can’t pop up in the backyard, contributing to an urgent housing shortage here. Thankfully, I understand that the city government is currently grappling with how to accommodate more density without breaking character and becoming another Albuquerque or, God forbid, Denver. It’s not going to be easy, but they did figure it out in the pueblos, after all, where communal living was the norm.

The city, as official policy, set out to dazzle out-of-state aesthetes and deep-pocketed empty nesters and it’s worked like a charm since well before New Mexico even was a state, for better and worse. But now that I’m here (and I do love it, by the way), let’s cool it a tiny bit with the charm and the change—the wait at La Choza is already too long.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?