After having read The Black Market this summer, I was itching with questions for author Charles Moore on how he accomplished this endeavor of single-handedly solidifying his place in the art world, the world of publishing and in the context of history in general not only as a Black man, but as a scholar and thinker. The book breaks down the monolithic stereotypes of who a Black collector, artist, or gallerist should be. Turning every page with fervor and determination to zero in on components I may be missing in my own career as all three, I instead felt sanctified down to the very last pages of the glossary. As a guide to collecting, it is a therapeutic tool toward self reflection on personal legacy. It gives confidence to someone like me with imposter syndrome as a woman of color in the art world. It solidifies that I am, indeed, in the Black market.

Capturing the multihyphenate nature of contemporary collectors and arts workers is its most important anecdote. I started my own small collection by purchasing artwork from my peers at the School of Visual Arts and curating independent exhibitions, but always felt that I was spreading myself thin as an artist, curator and gallerist and didn’t have the prestigious connections to give objects the care and prominence they deserve. Now, I feel refreshed about the future of my presentations and conserving the stories and objects of my community. Seeing many of my friends, colleagues and clients in the book made me excited that my experiences are now being inserted into history and archived. The Black Market proves that establishing common goals to create more accessible spaces and investments is the secret to success in the art world as a person of color, and in turn gives room for those multifaceted endeavors. It also reinvigorates the importance of an artist’s practice to have institutional presence and conceptual research rooted in prestige, rather than turning away from it because of past harm or intentional intimidation towards our communities.

When I first met Moore it became clear that we had similar goals to define Black historical legacy and institutions while staying true to our communities’ needs. The Black market is small, interconnected, and contrary to popular belief, quite accessible, yet coexists in many forms of practice. The Black Market illuminates the prospect of art professionals creating their own platforms and schools of thought and making themselves seen, without asking for permission.

Storm Ascher: When did you start writing about art?

Charles Moore: My first unpublished work was my first essays at Harvard. I wrote about Kiki Smith and her recurring use of Little Red Riding Hood as a theme. I also wrote an account of my experience at the National Museum of African American History & Culture: its collection and the architectural design of the building. Shortly after graduating in summer of 2019, I ended up meeting with one of the editors of Artnet for lunch. We talked about some ideas on writing about artists. Ed Clark happened to be having his first major solo show with an international gallery, Hauser & Wirth, that October. The first article I published commercially was an exhibition review of that Clark show.

SA: You’ve written for so many publications: meeting and interviewing art world professionals. How did you decide to compile all of this into a book?

CM: Writing on an exhibition or an artist profile is quite different from what you find in the book. I always thought about writing books though, and I even tried once and gave up, but I knew I’d come back to it later. I started reading a lot during the lockdown because I had nothing to do, as I was set to start a doctoral program at Columbia University, but not for a few months. After talking to a lot of people in the art world, I realized that there were some gaps in the literature. A lot of the books on art collecting had this assumption that you knew a lot about art already, and although I do know a lot about art, I felt like if you were a new collector, then you might be intimidated by how they structured the book. So I decided it might be a good idea to write a book about collecting in my way.

SA: So you already had experience art collecting yourself?

CM: I’m a second-generation art collector. My mother collected art for years, as far back as I can remember; I would say my earliest experiences with art and art collecting were when in middle school, and a little bit of high school. She really didn’t continue after that because she started to focus on real estate. But I never forgot those experiences and throughout my life, I was a frequent visitor of art museums. I lived in Europe for some time and visited art museums all over the world. I remember coming back from living in Italy for two and a half years in 2012 and watching the documentary, Exit through the gift shop, about an artist named Mr. Brainwash, and his experience documenting the works of street artists like Shepard Fairey. One of the narrators in the documentary is Banksy.

After an invitation to a wedding in Boston earlier that year led me to the ICA Boston, I exited through the gift shop and I saw a limited-edition print by Shepard Fairey. Obviously, his name was fresh in my mind and I could afford 50 bucks, so I bought it. From there, I began collecting more works by Fairey and a few other artists in the same genre. My experience and access changed over the years and I started to meet people, like art advisors, that shaped how I collect today.

SA: Actually getting into the structure of the book then, the first section highlights an artist from each decade from 1900 to 1990, then you transition to artists currently working. How did you go about writing to create this familiarity, this accessibility?

CM: Well, a lot of times in art collecting books, there’s this assumption that you know all about art already and now you just need the blueprint to figure out how to collect it. And I thought, ‘what would have been interesting for me 10 years ago, when I was thinking about collecting but hadn’t started yet?’I thought a sort of a primer, a brief introduction to art history would be helpful, and that highlighting one artist each decade for the last 100 years might be an interesting way of doing it.

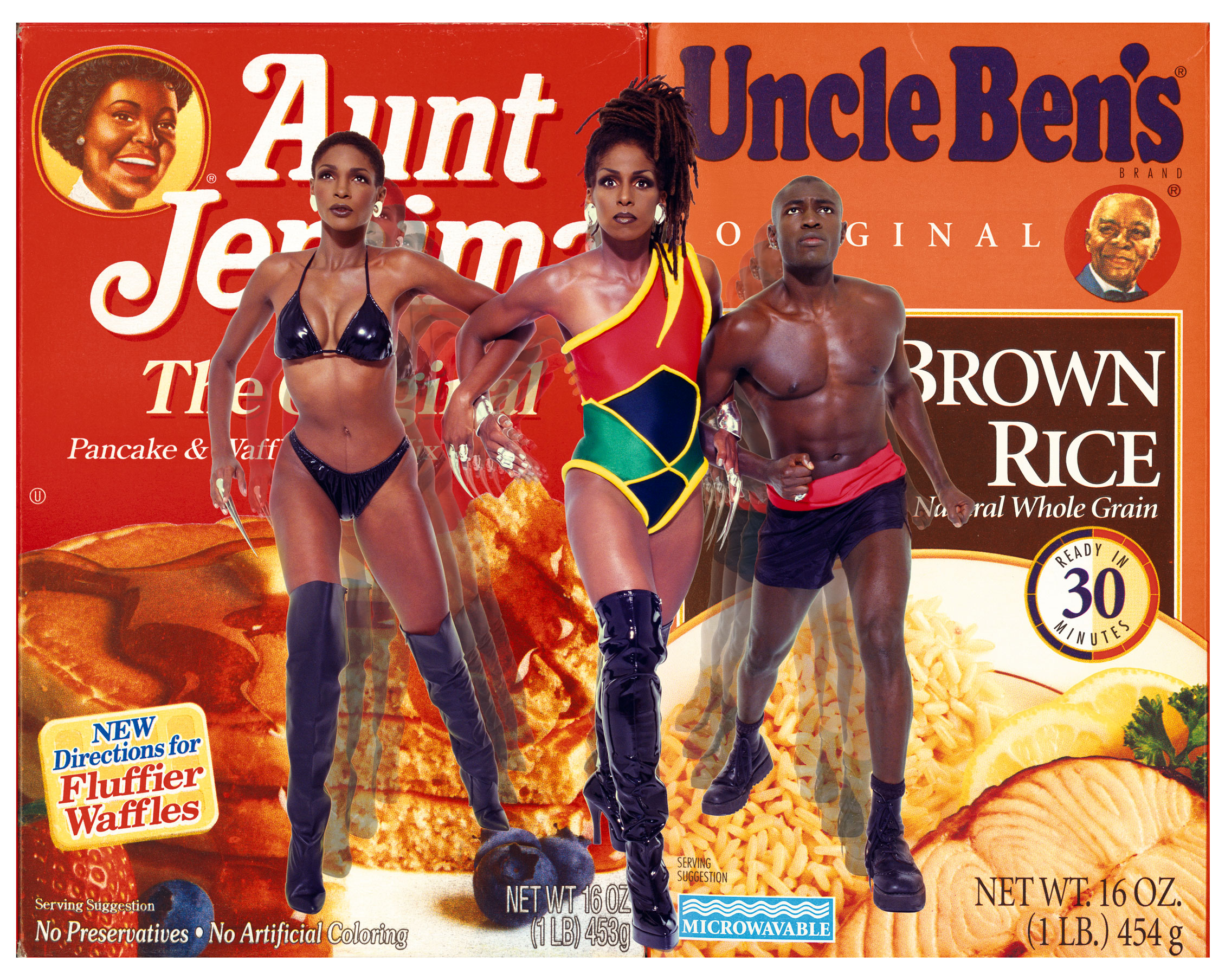

An interesting tidbit was who I put in the 1960s spot. It’s pretty hard to talk about Black artists in art history and not speak of Jean-Michel Basquiat. I actually wrote an entire section on him, and I decided to scrap it. He would be around the same age as Renee Cox right now since they were both born in 1960. Obviously, he’s no longer with us, but then I thought, ‘I never met Jean-Michel, and I know Renee Cox, and she’s a brilliant artist. Why not include her in this project instead of him, and keeps with the theme of an artist born every decade?’ And that’s why she’s there. A really close friend of mine asked me, “Why aren’t there photos in the book?” I hoped this would encourage curiosity.

SA: I actually learned so much about Renee from this book specifically. The art advisors and the artist liaisons section was so informative, too. And most likely, something people would keep to themselves. Being a gallerist myself, I know that those relationships are so private. I respect that you brought these people out from under the radar.

CM: I think the entire book is about lifting up the hood and showing how the engine works. Some of the people who are best capable of doing that are art advisors and curators; they’ll help you save a lot of time and a lot of money, and they’ll help educate you, not only about art but the importance of art collecting and protecting the culture and all sorts of wonderful, wonderful things.

SA: So the art advisors were happy to be acknowledged and not behind the scenes?

CM: You know, I’m kind of a behind the scenes kind of guy myself, as a writer, and I could totally understand and relate to the assumption of how they would feel. But I really do think they were excited about, not only the project, but about being more involved. We talked about some of the artists that I know personally, but a lot of the art collectors that are involved in the project were referred to me by these advisors. The project wouldn’t exist without their generosity. And it would be nice to give them a little bit of the spotlight for that.

SA: The Black Market includes a big section about the art collectors who collect Black art specifically. I felt it was very indicative of the fact that anyone can become an art collector, and each of those stories of how they came to collecting gave me so much confidence. You don’t have to be born in the art world, you don’t have to start out with a lot of money. Was that your goal, to just break down this stereotypical idea of what a collector should be?

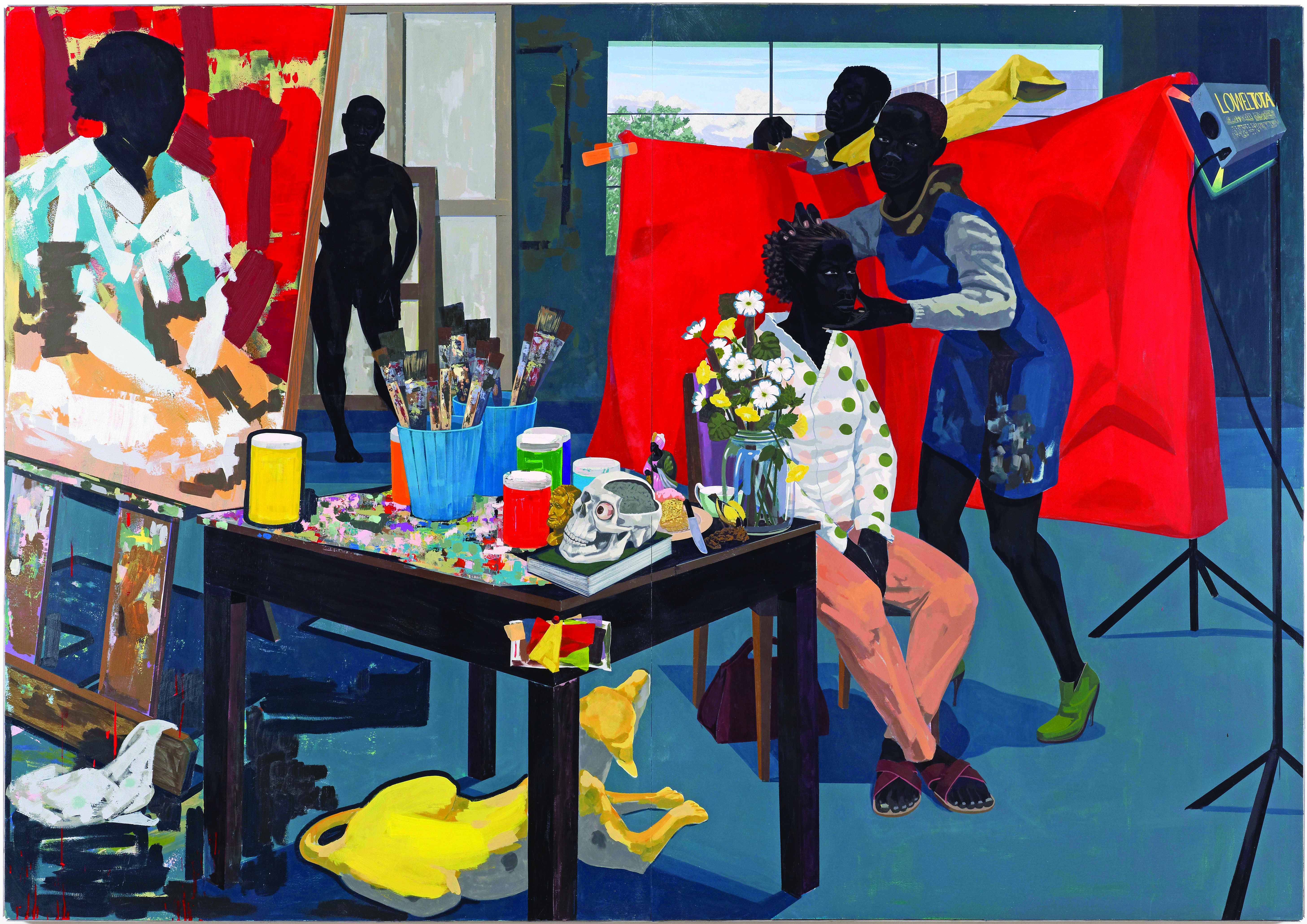

CM: You know one of the things that I think is a deterrent… It’s exciting to see headlines like, “Kerry James Marshall sells a painting for $21 million in the auction.” Most recently, an Amy Sherald work sold for $4.2 million after having an estimate of $150,000.

SA: That was such a low estimate by Phillips, by the way.

CM: Yeah, well I think those headlines are exciting, right? Fran Lebowitz said it best: “If you go to auction, out comes a Picasso, there’s dead silence. Once the hammer comes down on the price, there’s an applause. And we live in this world where we applaud the price and not the Picasso.” To me, that actually speaks very loudly on the exclusionary world of the art market. Although seeing headlines like that is exciting, how many people can buy a $4.2 million Amy Sherald painting? If you think that that’s the only price point for art, then that may be a deterrent for collecting art. I really wanted to applaud the art collector, because only a couple of the collectors that I highlighted are millionaires (I think). Most of them have normal jobs like most of us have. That was the point I was making.

SA: Do you think it is important for Black collectors to also collect non-Black art?

CM: I think that is up to the collector. Nevertheless, I do think it’s important for Black collectors to know and understand the work of non-Black artists. If you can’t talk about contemporary art without mentioning Warhol, Rothko or Basquiat, then you should know all of them. It could help you understand why Kanye chose Condo to do the cover of his album; why Fairey was selected to design the campaign poster for Obama or why Louis Vuitton collaborated with Murakami/Kusama to design handbags, and Dom Perignon with Koons.

SA: So, who is the Black market? Who is this book meant for?

CM: Well, I think I do a decent job of highlighting the contributions that Black artists have made into the canon and helping write about a few of those stories. I think the book also, as you so duly noted, gives the reader a peek into the art world, in the way of art galleries, museums, auctions, art fairs, art schools, artist’s residencies… And then there’s a carefully curated group of Black collectors. I talk about their journeys. Specifically, I wrote this book in a tone that allows for anyone with the curiosity about any of those subjects to learn from this book. And anyone who is curious about culture, is who this book is for.

SA: Of course, this could be read by anyone, but the title clearly gives way to a Black audience to find their voice in the world of collecting. Why is this so vital right now?

CM: There are many books on art collecting, that don’t necessarily give an obvious suggestion on who those books are for. But the collectors they interviewed, and the art works within their collections state pretty clearly who they’re talking about and who might find the narratives and stories interesting. Now, I have read most of those books, and this is not to say they aren’t interesting, well-written and informative. They are. I’ve learned from reading those books. However, if one picked up those books and pondered why none of the collectors were Black, and the majority of the artists discussed in those books weren’t Black, there could be an assumption that inspiration could be lacking for a Black person reading. They may ponder why they can’t see themselves in those stories.

I wrote this book from this perspective: I’m Black. The scholar I asked to write the foreword is Black. The artist I commissioned to design the cover is Black. Every collector I interviewed for the book is Black. The art advisor, artist liaison, gallery owner and two art students are all Black. I wanted the book to be from their eyes, their gaze, their experiences and their influence. Again, anyone can pick up this book and learn from it…just like any of those other books on art collecting. And this one, The Black Market, even more so. Because I wrote this with two assumptions in mind of the reader: They may have little or no experience in the art world, and they are intelligent and sophisticated.

SA: Why is it so important to document your experiences and solidify your legacy?

CM: I was once told, “If it’s not written down, it didn’t happen.” History is always told by the victors. I choose to write because I’ll be part of those who tell the history. I also want to preserve my own legacy in this space by writing about the stories I want to tell. I want to write about the artists I admire, and inspire a generation by telling them about the art collectors who own pieces of this culture.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

in your life?

in your life?