The 1990s was a decade characterized by massive cultural and economic changes across the globe, many of which were embodied in New York City. The booming worlds of finance and banking had by the mid-1980s transformed the American metropolis into a global hub for art, fashion, and entertainment, realized further by the wide availability of space, relatively affordable rent, and the long historical presence of a flamboyant artistic milieu. With the city’s sub- and counter-cultural graffiti and hip hop scenes having shown to be highly profitable in the previous decade (evidenced with the meteoric rise of graffiti artist and painter Jean-Michel Basquiat), the 1990s saw a sharpened interest in accessing the untapped economic value of subculture, its images, and most importantly, its marginal identities. From grunge to neo-hippie, the 1990s saw identity and its politics usurped and stylized by capital; fashion corporations in particular, who transformed the “alternative” into product ranges available in mass-market fashion retailers like the Gap (brilliantly explored at the time by the NYC art collective, Artclub 2000). Images of youth-driven multiculturalism were abundant in the consumerist landscape, most vividly in the advertisement campaigns of Benetton and Calvin Klein, who propelled harmonious images of racial and sexual diversity across the city’s towering billboards. Increased social fragmentation led to a new cultural emphasis on differentiation and the maximization of individual choice, which manifested via personal consumption by the emerging Generation X, who in this time overtook baby boomers as the dominating spending demographic in the fashion market. In this emergent “economy of cool,” corporations allocated unprecedented resources towards branding with the aim of becoming transcendent image-brands at the centre of the youth-cultural zeitgeist.

Because of these developments, the 1990s also marked a significant moment for fashion and style within the context of fine art. The efforts of 1980s postmodernism had challenged previously established hierarchies of cultural forms, rendering advertising, consumerism and representation a genuine concern for fine artists. In these decades, fashion continued to become an increasingly central subject of popular culture, and thanks to avant-garde designers such as Rei Kawakubo, John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, and Martin Margiela, an increasingly legitimate form of artistic expression in its own right. While art had been deemed the ultimate center of cultural attention in the 1980s, as illustrated by the rise of the East Village art scene, it was now fashion that was rendered as the city’s “last gritty, gutsy avant-garde,” insisting on “acting out dissonance and stirring up the kinds of social ruckus that art once lived by,” as art critic David Colman observed in Artforum in 1995. With the US recession of the early 1990s as its socioeconomic backdrop, fashion extended art’s pre-occupation with independently-organized cultural activity produced with its own milieu as its main intended audience. Central to all of this was the city’s thriving nightlife scene, which, as Elizabeth Currid-Halkett notes in The Warhol Economy, had long been famous for mixing the social worlds of art, fashion, music, and celebrity. She notes, however, that the 1990s saw NYC’s nightlife transform from a place of raw cultural production and dense creative community building into an increasingly cost-prohibitive site of networking and career building—not least due to the rapid gentrification of the city, which saw rents rise persistently throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Here, artistic self-fashioning became a crucial component to living and working in the city’s expansive cultural scene: if not to impress one’s peers, then to get professional attention—and thus, access—to the city’s art, fashion, and advertising industries.

It was in this environment that a community of young creatives in the Spring of 1993 started organizing parties under the name of Bernadette Corporation. Hosted in the Thierry Mugler Room of Club USA, Peter Gatien’s notorious nightclub just off the then-still gritty Times Square, it was a brief gig that lasted only seven weeks, but one that nonetheless offered the group a notable presence within the city’s art world. Conscious of the scene’s thirst for youth and celebrity (the main space of Club USA was hosted at this time by infamous promoter and Club Kid, Michael Alig), the group chose an opaque “corporation” as an organizational structure, seeing as it served as “the perfect alibi for not having to fix an identity.” Contrary to the figure of the artist-celebrity, they found a faceless and amorphous corporation an ideal way to evade the demand for a marketable artistic identity, allowing them to do “whatever they wanted—and not be liable.” The group’s activities were raw and improvisatory in nature, and would include so-called “fascion” performances (“the simultaneous practice of fashion and fascism”) involving group-coordinated dress-up, exemplifying their dystopian approach to style-driven self-marketing. As their promotional material explained, they approached “persons as products” and accelerated this mentality to an outré extent in their appearances in clubs and streets around the city, organizing conceptual flea markets or “fashion bazaars” in SoHo parking lots, and even running a short-lived café on Allen Street named DMC (Documents and Manifestos). The group’s member list was fluid and opaque, counting anywhere from three to a dozen people, most of whom were students or recent graduates from the city’s various art schools. “[A] band of 6 stylized artists and fashion designers between the ages of 22 and 25,” an early press release read, “we hope to produce the spectacle of movement, and thus attract a lot of media attention. We will remind you of something you’ve seen before, but just can’t place your finger on.”

The group’s interest in identity and its impending commodification naturally led them to the world of fashion, and by 1995 they re-launched as an operational fashion brand, legally incorporating themselves at the New York Department of State. At college, original members Bernadette Van-Huy and Thuy Pham had taken a strong interest in postmodernist theory by the likes of Baudrillard, and Van-Huy in particular was keen on bringing it to the fashion world, “approaching it like an art project.” They rented a loft on the Bowery, which would come to serve not only as the brand’s atelier and corporate “headquarters,” but as an improvised home for many of the members in the coming years.

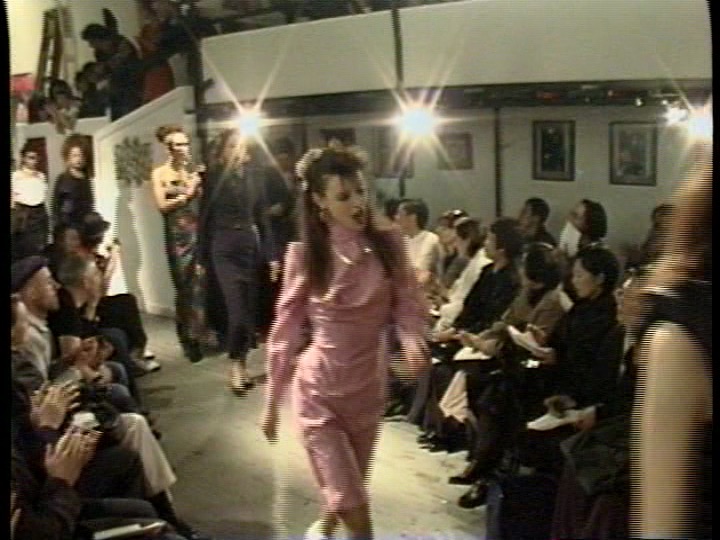

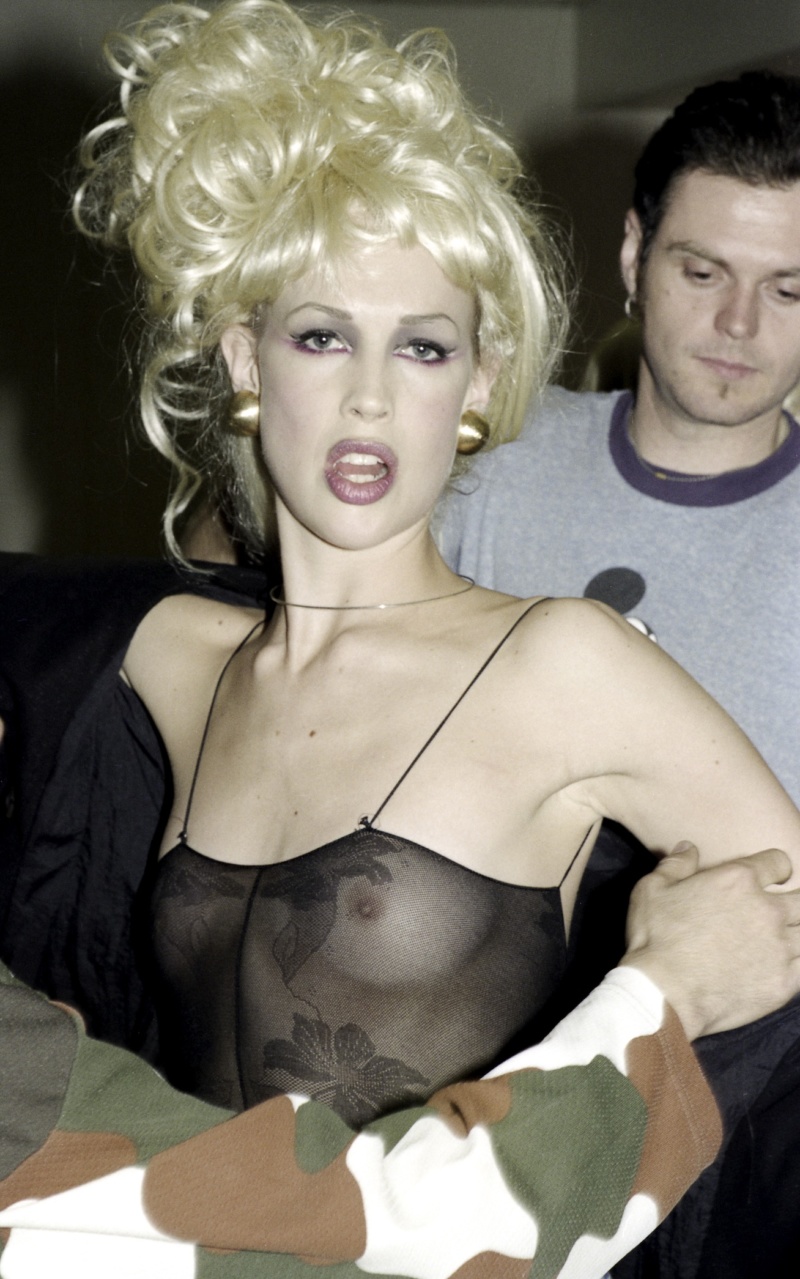

Bernadette Corporation Fashion Line presented their first collection, F/W 1995, at the East Village music venue CBGB Gallery in the Spring of 1995: an unlikely juxtaposition of minimalist dresses, thrift-store finds, and deconstructed street-wear worn by an army of highly accessorized models, most of whom were styled in quintessential “chola”-style get-ups, and who walked the runway with a provocative attitude, chewing gum, smoking, and gesturing aggressively to each other as well as the audience. The following collection simulated both yuppie evening wear and “white trash” silhouettes, with all models styled in voluminous blonde wigs and fake pearls. Their F/W 1997 collection “Hell on Earth” presented neck tattoos on Asian models, white women in cornrows, Michael Jackson lookalikes, and Latinas styled as Goths. Appearing as semiotic hacks of trends and taste-hierarchies of clothing, the collections clashed and misrepresented codes and syntaxes from the world of high fashion, “ethnic” street fashion, and the blandest mall frocks. As the group operated on little to no funds, almost half of the clothing was either borrowed from sportswear brands such as Fila and Nike, or sourced from secondhand shops; however, this also served as a conceptual strategy, presenting Bernadette Corporation’s own sartorial vision as one that heavily relied on the appropriation of others’. In their own words, the group combined, “the markings of ghetto cultures, the silent impenetration of corporate identities, the collapse of social order, and pure formal/theoretical manipulation;” while the goal was to “put on fashion shows that play like a pop song and read like propaganda, thereby giving feeling and spirit to these times.” …

Read the full chapter on Bernadette Corporation in Fashion Work 1993-2018: 25 Years of Art in Fashion, available via DAP.

in your life?

in your life?