For Karen Robinovitz, slime has an almost metaphysical presence, with the power to fill a spiritual void. Robinovitz is the co-founder of the Sloomoo Institute (the name came from a viral Insta-behavior where people were saying, ‘replace the vowels of your name with oo and that’s your slime name.’” Karen, for example, is Kooroon)— an 8,000 square-foot tactile immersion-scape that opened in late October in Manhattan’s Soho. She recounts her own spark of creative intervention with gut-wrenching clarity.

The tragic death of Robinovitz’s husband left her in a crippling depression. For a year, it was nearly impossible to leave her apartment. She describes a visit from close friends with their daughter Mattie, who arrived—true to pre-tween, zeitgeist—with slime and a recipe for a fresh batch to make in the kitchen to help pass the time. “The minute I touched it, I was in heaven,” Robinovitz recalls of the transformative moment. “Four hours later, I was still playing with Mattie, completely ignoring my adult friends, in what I know look back on and say, ah, a slime high. All of the sadness and grief wasn’t in the forefront of my mind. For the first time that year, I realized I was smiling.”

After that, by her own account, she quickly became a full-fledged addict, ordering large quantities from “every major slime maker,” through their Etsy or Shopify portals. The more she slimed (at Sloomoo, slime is a verb), the more it grounded her in the present—part-meditation, part-activation. “Little by little, slime enabled me to live again, because it was engaging all of my senses, except for taste,” Robinovitz explains.

At quick glance, with its ever-present queue on the sidewalk, critics might mistake the Sloomoo Institute as merely another hyper-sensory “museum” or pop-up installation, designed for Instagrammability above all else. But that would be missing the painstaking thought and art-world gravitas behind Robinovitz, and partner Sara Schiller’s, achievement. Both are avid art collectors; Robinovitz, serving on the board of the Brooklyn Museum and the Bronx Museum of Art; Schiller, a force behind Wooster Collective, a highly prominent street art blog, and co-author of “Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art.”

Working with Method Design (who created Sloomoo’s sculptural vats and designed the space) and wallpaper-cum-mural design firm, Flavor Paper, the space’s pastel ombre palate takes inspiration from Rob Pruitt’s Suicide Paintings. “The name is a tough one,” admits Robinovitz. “But I’ve always found them incredibly ethereal. While they look physically beautiful, there is much deeper meaning to Pruitt’s work.” Walking through Sloomoo, she gestures to upside-down mannequins in the window, and references Antony Gormley’s and Bruce Nauman sculptures. “Slime has a way of flipping everything on its head,” she adds. “We want everyone to feel like it’s a different world.”

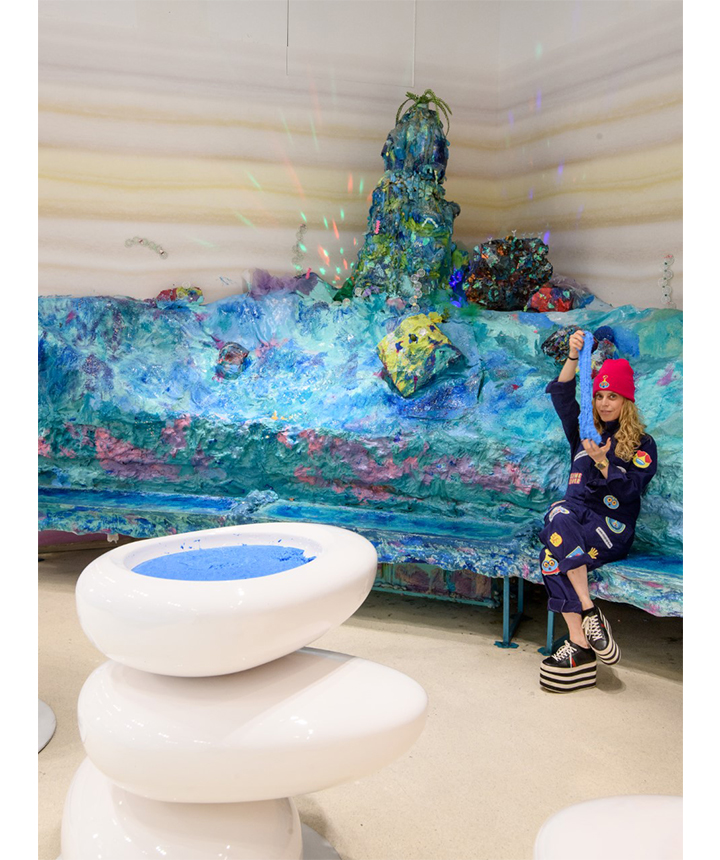

Indeed, plenty of high-profile contemporary artists have helped Robinovitz and Schiller achieve their alternate microcosm. Sloomoo’s Cove, the delirious, glow-in-the dark grotto by art duo Jen Catron and Paul Outlaw, known for their playful but pointedly political artworks and performance pieces, is worth the trip alone. Most recently, the artists monumentally oversized chocolate sundae and kitchen sink, both self-circulating fountains, graced the Brooklyn Museum. “When you’re inside their Sloomoo room, you aren’t in a normal universe,” Robinovitz says, “exactly how Jen and Paul’s installations are.”

On equal footing is Sloomoo’s slumpie—specked with glitter, part-sculpture, part-couch—by filmmaker and artist, Jillian Mayer, who’s had solo exhibitions at The Perez Art Museum, Kunst Aarhus and the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha. “I wanted to make something that people would automatically feel comfortable on and understand that it was an inviting place to have a seat,” reflects Mayer. “At the same time, I wanted to make a bench that looked like it was being engulfed in a slime puddle and was absurd, that still sort of functioned as a stage.”

“It’s made of fiberglass but it looks wet and slimy,” Robinovitz notes proudly of Mayer’s artwork. “She’s not only using the materials she uses for the slumpies series that have been shown at MoMA PS1, she’s borrowing from the materials we use in slime to kind of bring her fine art into our space and to bring our space into her fine art.”

in your life?

in your life?