My debut novel—a coming-of-age story titled Exquisite Mariposa—makes modest use of the motif of butterflies. It was only after I sold the manuscript that I realized what I had created: a book about maturation and transcendence, set in an apartment called La Mariposa (butterfly in Spanish), that, somehow, doesn’t once use the word “metamorphosis.” Exquisite Mariposa was the working title of a Google Document I would write in whenever I couldn’t do anything else due to scarce resources. Over the course of three years, I wrote to inspire myself out of a meek triad of financial insecurity, social anxiety and attraction to abusive narcissists. Cocooned in pivotal meditation, my mind rarely made note of butterflies then.

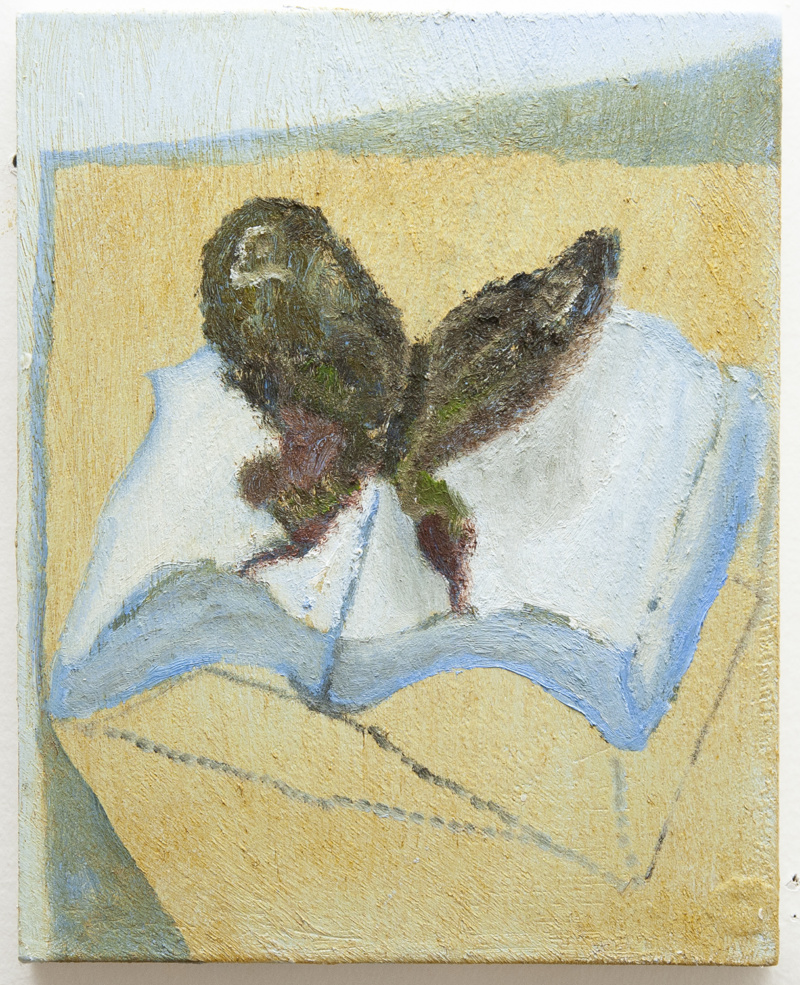

In the months after I finished my novel, I watched butterflies swoop and tumble in my Los Angeles front yard every day. Nine months later, I sold the manuscript to Soft Skull Press and started clocking the creature in art and pop culture, hunting for a book cover. My first cover concept involved a sheet of white paper folded in half (my own handcrafted mockup) with one butterfly wing drawn on each side of the crease. Opening the book would spread its wings. I may have stolen the idea to imagine book flaps as butterflies from American artist Matt Hilvers, who often figures the two together. Then again, we both watched Reading Rainbow as kids. In the opening sequence of that TV show, hosted by my first crush, LeVar Burton, a cartoon butterfly animates adventure scenes around kids who read in public space, before transforming itself into a book.

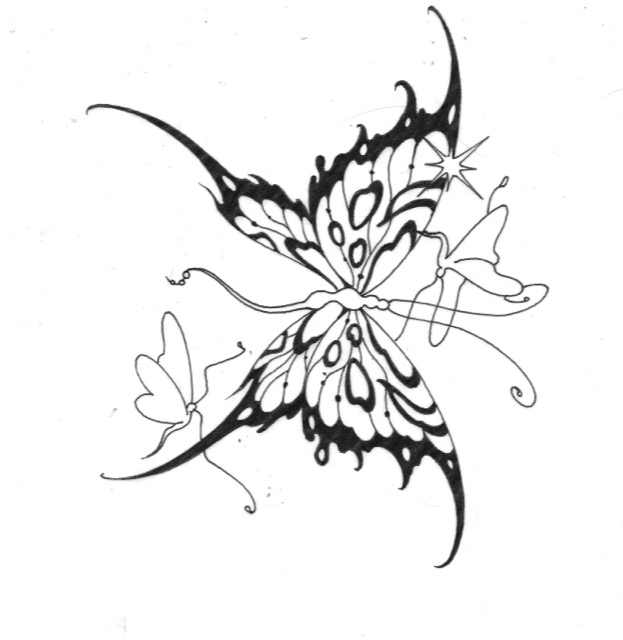

Butterflies are a perfectly exaggerated metaphor for the universal phenomenon of change. As an icon, butterflies are most sincerely embraced by women, children, artists, acid heads, and trans, queer, and sober folk. Sometimes called the “kiss of God,” a butterfly comes cockhead pink in the 1971 gay erotic film Pink Narcissus and rainbow-bright care of Lisa Frank. Slapped on performance fliers by pornstar-cum-politician Ilona Staller, carved into AA merchandise, inked below Drew Barrymore’s 1990s navel, and an evergreen fixture of girl-gendered clothing, the butterfly is a reassuringly popular guiding symbol. A testament to their versatility, butterflies are everywhere—on backpacks, tank tops, earrings, hanging from rearview mirrors, and tattooed between Venusian dimples—representing, in turn, beauty, innocence, fragility, femininity, nervousness, metamorphosis, God, and irony. There’s gotta be nearly as many butterflies as there are cash registers in New York (where I now live) though here, I see at least twenty images of butterflies for every “real” one (in L.A., the ratio is more like 1:1.) Often psychedelic, like Los Angeles sunsets, butterflies’ vivid natural coloring serves as an “ad board,” it’s said, for how poisonous they are. The butterfly as femme fatale.

When white men led Hollywood, their fatale characters either had to be tamed (married) or killed off: glorious wildness squashed. Biological butterflies, along with bees, sea turtles, and soon, every species, risk the latter fate if patriarchal industry doesn’t wise up and curtail CO2 emissions immediately. This is Western Patriarchy: you praise, objectify, and even idolize a creature while simultaneously killing her.

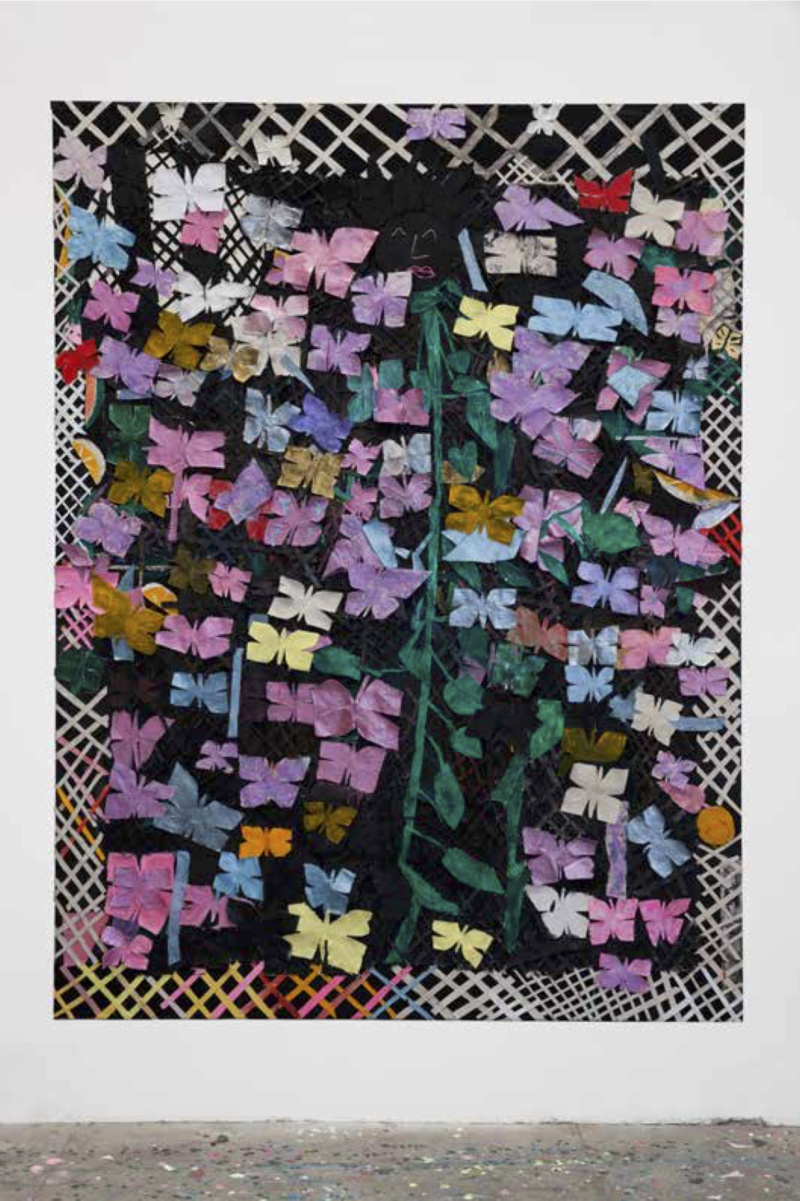

Butterflies are so prolific as idols that every other Google Image Search for a major artist or designer plus “butterfly” will produce a relevant hit. With a working background in fashion and art, I didn’t even have to hit enter to summon mental images of butterflies by Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, Valentino, Gucci, Jack Goldstein, Will Sheldon, Torbjorn Rodland, Charles James, Alexander McQueen, Lana Del Rey, Jean Paul Gaultier, Dolly Parton, Off-White, Crazy Town, John Galliano, Jeremy Scott, Moschino, Shûji Terayama, Amalia Ulman, Susan Cianciolo, Sojourner Truth Parsons, Alake Shilling, Vladimir Nabokov, Lynn Hershman Leeson, and Supreme.

Even larvae get some love, though not enough. Jeff Koons has plastic-toy caterpillars scale ladders. And there’s the iconic pop kids’ book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, reported to have sold a copy per minute since its publication date in 1969. My no-compete favorite leaf worm-like artwork is “The Buddhist Bug,” in which Cambodian-American artist Anida Yoeu Ali wears a saffron-colored costume that can stretch up-to 40-metres in length or retract into a ball. Made in the color of Buddhist robes yet worn with a Muslim headdress, Ali’s “Bug” depicts the “spiritual turmoil” of existing within two religious traditions.

Faith and belief—how are they different? How do they direct us? Where do they come from? These are the big, motivating questions of Exquisite Mariposa. In the image that did eventually become my book cover, a strawberry blonde doll strides in an aquarium with a miniature “I WANT TO BELIEVE” set prop poster from The X-Files on the wall. A heart made of glitter decorates the floor, as does a slice of broken mirror, cold green tea bottles, and plastic “grass” from a sushi container. The top of the aquarium is covered in craft store gold star wire, coiled to evoke barbed wire. It’s a photograph of one of many dioramas from Maggie Lee’s 2016 show “Fufu’s Dreamhouse” at Real Fine Arts in New York. The image couldn’t represent Exquisite Mariposa better. Every detail in Maggie’s diorama can be found in the book: fashion, fame, astrology, love, cutting narcissism, prosthetic nature, health products, wanting to belief in something unknowable that’s keeping you enclosed, and even the enclosure itself. In Chapter 08, one of my young-girl characters describes her anxiety disorder as being, “like an aquarium. I’m in this glass box and I can see you all on the other side and I want to join, but I can’t break through.”

Since reading Exquisite Mariposa, my friend Mara has taken to sending me videos of butterflies. She joins my friend Sojourner and me in this lepidopterology of sorts. We collect icons and iconic documentation of the endangered species. When Sojourner (Truth Parsons) paints butterflies, they have many sides. While I doodle the insect in two strokes, like loosely squashed symbolic-heart tops, Sojourner takes between six and sixteen lines of paint, or slices of canvas, to make her sharper flying flowers. Likewise, Mara (Mckevitt)’s choices are so Mara, which is another thing I’ve come to love about butterflies: as with language and clothes, our relationship to them can become so legibly personalized. In one video Mara recorded and sent me, from late-spring, a palm-sized black and orange butterfly flaps into the spotless window of a Rite Aid, trapped inside. In another, shot in night mode, a glow-in-the-dark caterpillar wiggles on a black background; it looks like she’s scaling a single thread of spider web when she’s not squirming in the void.

in your life?

in your life?