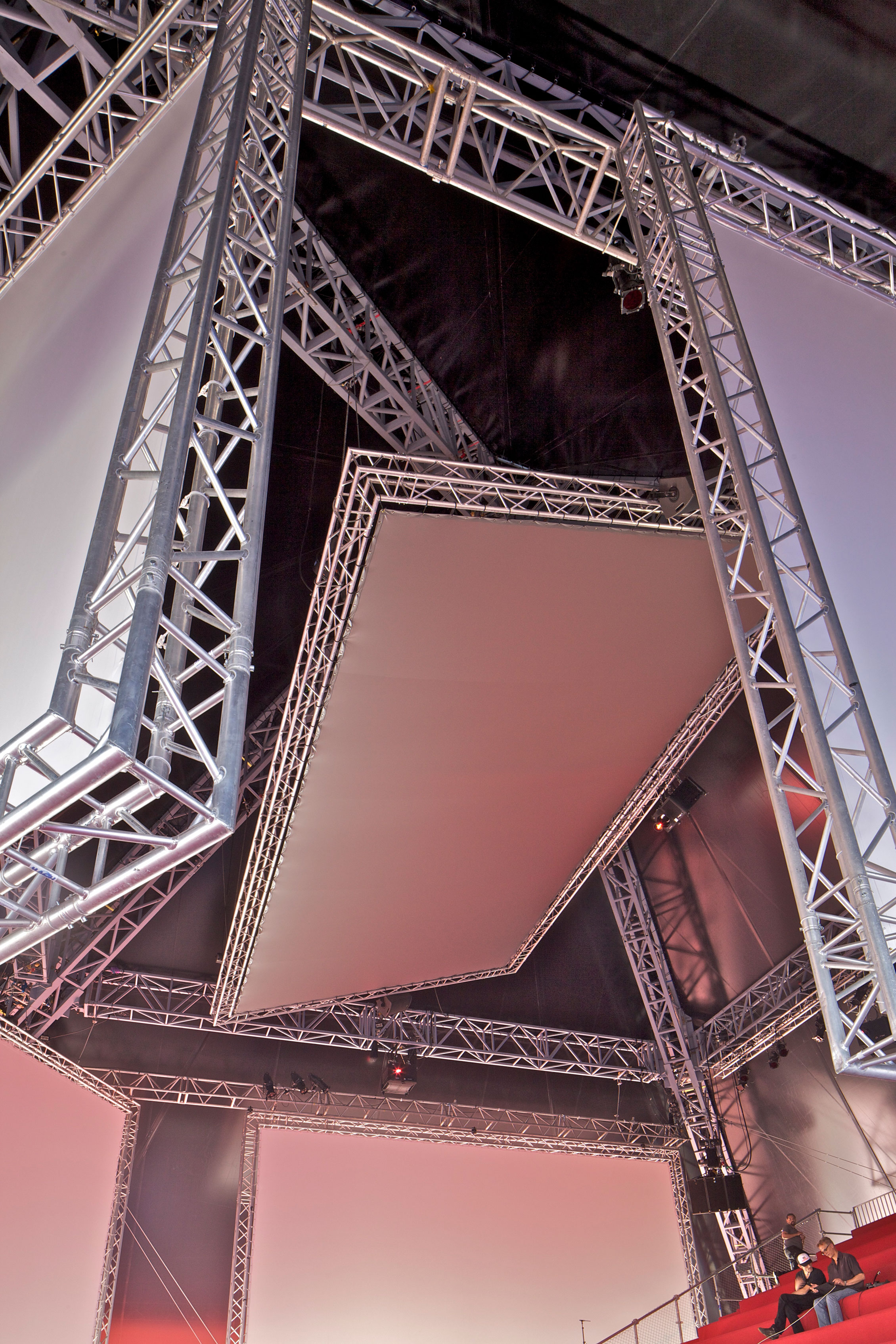

In the woods of Calabasas, the gated Spanish mansion community in the hills above Los Angeles, Kanye West has been up to something. “We stroll out into the chilly, starless night, and I follow him up a dirt path deeper into the woods for several minutes until,” Zack O’Malley Greenburg wrote last year, “he stops at a clearing and looks up, wordless. There, with the hazy heft of something enormous and far away, stand a trio of structures that look like the skeletons of wooden spaceships… West leads me inside each one.” Those unfinished structures were oblong, but this summer a set of four half-built domes standing up to 50 feet high appeared in their place. Inside of them, West hoped to create spaces that are spiritual and otherworldly and, if all goes well, might one day be used as low-income housing around the world. His interest in domes is ongoing. Earlier this year, he abandoned his headlining slot at Coachella because promoters wouldn’t build a gigantic, immersive video dome for him to perform in; the previous spring, he’d abandoned New York’s Governor’s Ball for the same reason. Even the man who has everything rarely gets what he most wants.

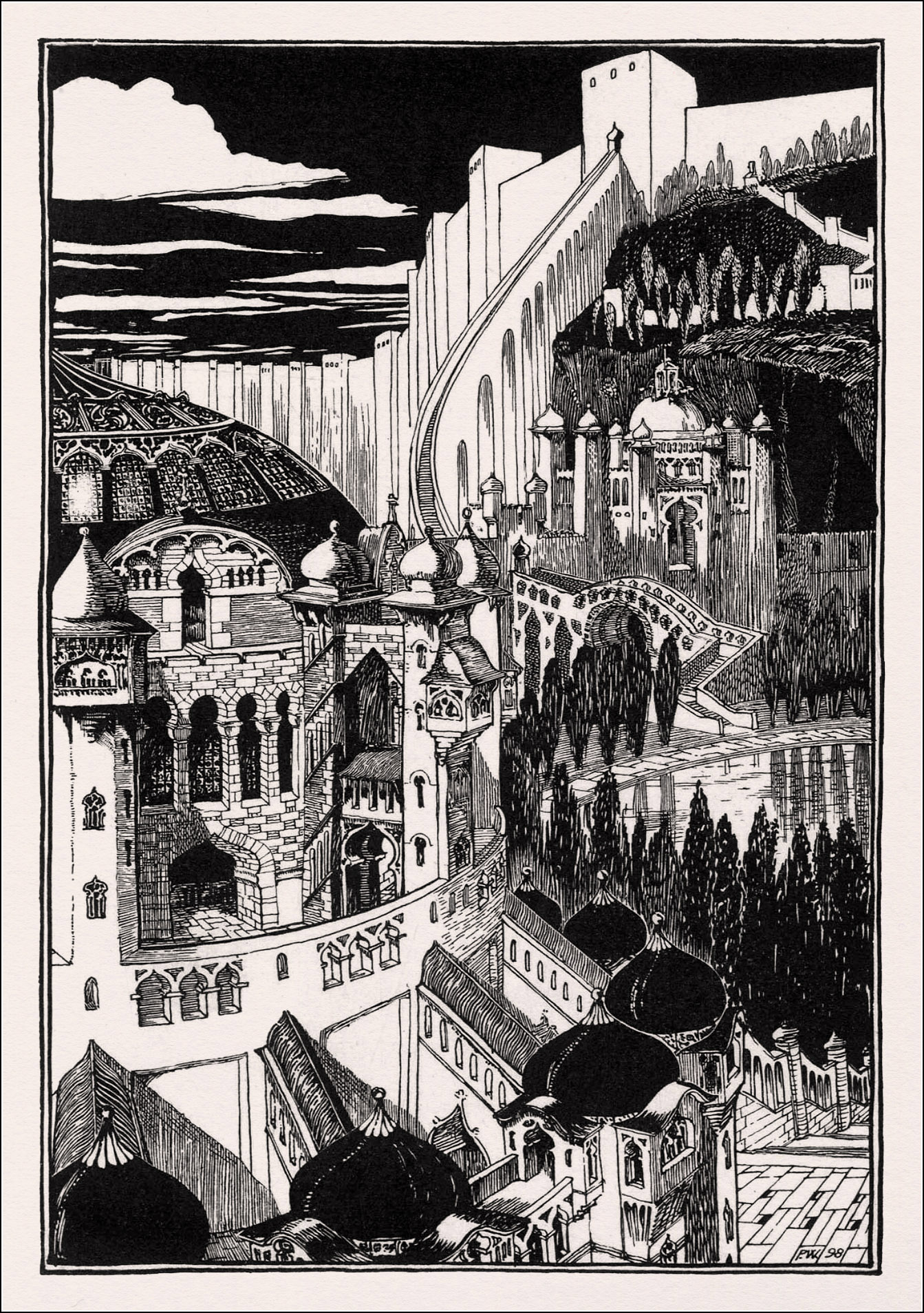

If there’s a lesson to be learned from West, it’s surely this: if you want your dreams to come true, you have to build them for yourself. He’s reportedly drawn inspiration for his latest project “from every period of man’s existence on Earth,” and his designs join a great lineage of magical, heavenly domes reaching back through Kublai Khan’s icy pleasure palace in Xanadu, the Duomo placed on top of the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore by Filippo Brunelleschi in Florence, where West and Kim Kardashian were married in 2014, Ray Bradbury’s spherical Spaceship Earth at Disney Epcot, and the Buckminster Fuller-inspired geodesic dome in New Mexico that Marianne Williamson dropped out of college to grow vegetables in.

West, who’s said many times that artists shouldn’t be limited to just one artform, is the closest thing we have today to a renaissance man, and his architectural debut has been coming for quite some time. It was back in the fall of 2013 that he first mentioned to a perplexed BBC radio interviewer that he was hanging around with architects mostly and working with five at a time. “Time spent in a bad apartment,” he lamented, “I can’t get that back.” Shortly afterwards he began collaborating with Belgian architect Axel Vervoordt on his family home in Hidden Hills, which took years to complete. The space is austere and minimal and drawn in off-white tones. The ceilings are arced and chapel-like. The floors made of delicate cream plaster that can only be repaired by specialist Belgian craftsmen; visitors are asked to wear soft cloth booties over their shoes.

Before that, for the Cannes Film Festival in 2012, West had commissioned Rem Koolhaas’ practice OMA to make him a pyramid-shaped cinema with seven screens. In the summer of 2013, he’d told The New York Times that the greatest inspiration for his just-released record Yeezus was a Corbusier lamp from 1954 in the living room of his apartment in Paris; most likely a Lampe de Marseille, although he did not specify. To really enjoy the record, imagine yourself listening to “Bound 2” in the warm glow of a Lampe de Marseille in a loft above Rue Tronchet. “Like I say,” he told the Times, “I’m a minimalist in a rapper’s body.” Last May he announced that his fashion and lifestyle brand Yeezy was going to begin making homes, and in June, a couple days after releasing his album Ye, renderings of his first Social Housing Project, designed in collaboration with Petra Kustrin, Vadik Marmeladov, Jalil Peraza and Nejc Škufca, were posted online. This scheme, made from a prefabricated concrete shell in strict rectilinear forms and shades of grey, was itself very Le Corbusier and suggested that West’s taste in architecture would be as brutalist as his taste in fashion: raw, stripped-back materials, simple finishes, zero embellishment, naked surfaces. His latest prototypes for low income housing, however, take a different turn.

All four domes in the woods of Calabasas have different proportions, round or arched entranceways and perfectly circular apertures on top to let the sunshine flow down in through. Much like the bodily aesthetic his wife and stepsisters have popularized this decade, they’re curvier, wavier and and more voluptuous. He seems to have eschewed straight lines altogether, evoking the Catalan Modernist Antoni Gaudi, who once observed, “There are no straight lines or sharp corners in nature. Therefore, buildings must have no straight lines or sharp corners,” and the psychedelic Viennese dreamer Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who once called straight lines “godless and immoral,” depraved signs of our lost connection with nature’s forms.

What I most admire about Kanye is his vaulting ambition. In late 2013, after returning from Paris, he went to the Harvard Graduate School of Design studios, jumped up on a desk and shouted, “The world can be saved through design.” He’s a perfectionist and an idealist with boundless vision, and he’s endlessly frustrated, and who can’t relate to that feeling of frustration when the projects that you’re making are so distant from the projects that you’re dreaming of. “I believe,” he told the design students at Harvard, “that utopia is actually possible, but we’re led by the least noble, the least dignified, the least tasteful, the dumbest and the most political,” and I think he’s right. Last year, wandering Calabasas’s rolling green-and-ochre hills with Charlemagne the God, West spoke warmly of “the relationships I have with architects, my understanding of space and sacred proportions, just this new vibe, this new energy. I’m tired of the McMansions, all the Spanish roof homes,” he said. “That shit wack, bro. It’s trash, bro.” Rather he was going to start developing cities, whole communities. He’s dreaming of housing, according to a source close to him, that “he believes will break the barriers that separate classes,” and why not?

Before that, West does have some more practical concerns to deal with. His neighbors have already contacted L.A. County’s Department of Public Works and complained about his construction site; as they would, because the whole reason for living inside a walled city is that nothing out of the ordinary should happen, that nobody’s going to start raising up models of utopian communal Metabolist architecture for a classless society in your backyard. At the time of writing they’re being torn down, before they’re even finished, but that doesn’t matter, that’s hardly likely to stop him. He rarely gives up, and isn’t afraid of making a fool of himself or failing in plain sight. In 2013, again, back when he was still trying to make a name for himself in fashion design and was widely derided for doing so, West complained about how he hadn’t been taken seriously during his internship for Fendi, how, “Me and Virgil [Abloh] are in Rome giving designs to Fendi over and over and getting our designs knocked down. We brought the leather jogging pants six years ago to Fendi, and they said, ‘No.’ How many motherfuckers you done seen with a jogging pant?” Six years on from that, Abloh has been appointed Men’s Artistic Director of Louis Vuitton and West has grown Yeezy into a billion-dollar brand; who knows where his dreams of building a new city will take him.

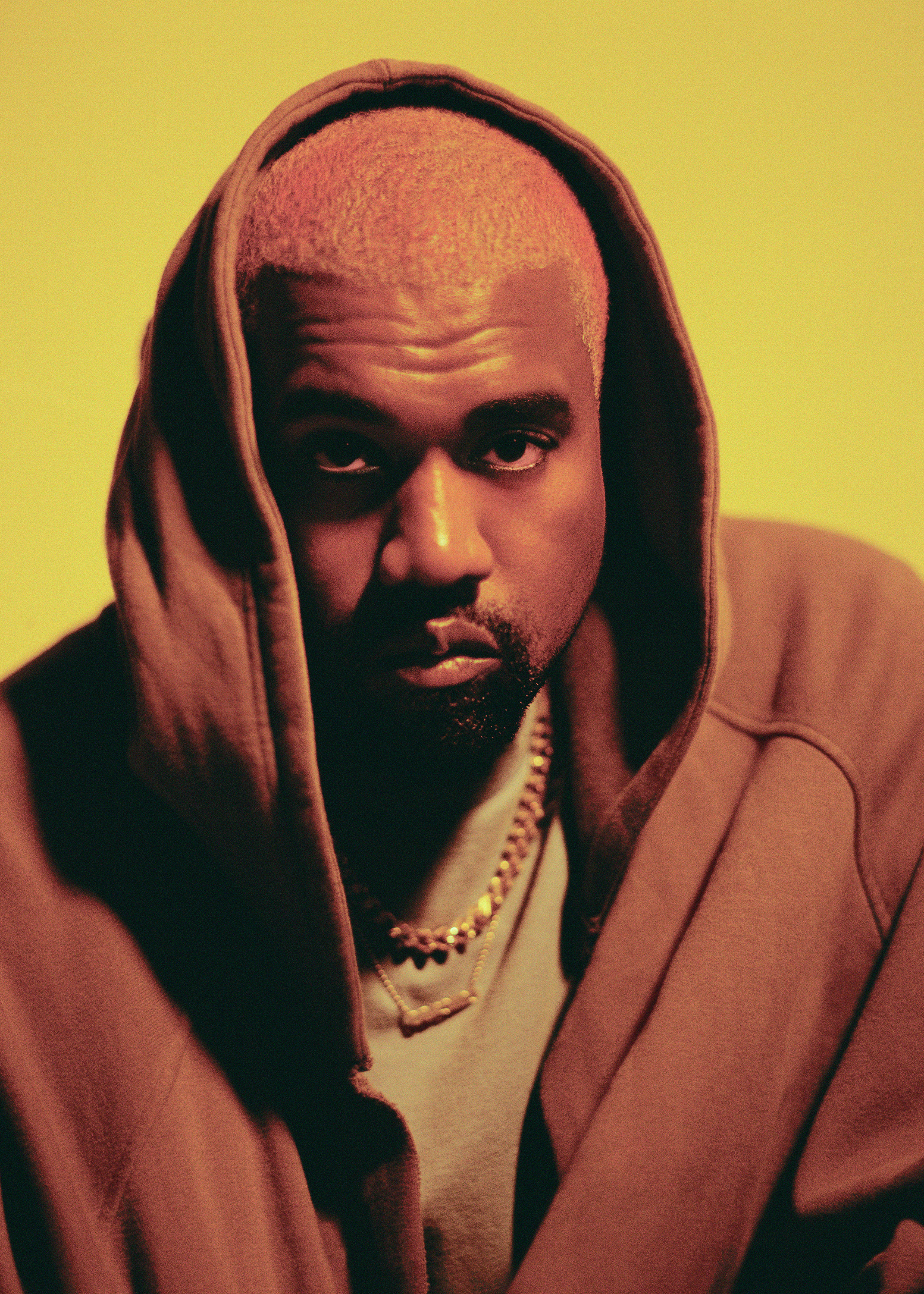

Read Heji Shin’s account of showing her portraits of Kanye in the Whitney Biennial here

in your life?

in your life?