Where the Land is Free, an exhibition presented by Poetry for the People and on view at Bakehouse Art Complex in Wynwood, Miami, utilizes poetry and art as a starting point for community activism and social justice. Watch an exclusive video of the show’s opening night here, created by FXRBES and shared generously by VOICES: Poetry for the People, and read our story as Aja Monet, a co-founder, shares the group’s story and the show’s mission.

“But when freedom found itself threatened throughout the world in 1943, surrealism…wanted to sum up the entirety of all its efforts in one magical word: freedom.” When Suzanne Césaire—the Martiniquais writer, anti-colonialist activist, and wife of poet Aimé Césaire—wrote this (part of her 1943 essay, Surrealism and Us), she was connecting Surrealism and anti-colonialism, black Caribbean identity and poetry. A Surrealist herself, Césaire insisted that art—poetry in particular—would motivate “this most deprived of all people” to rise up.

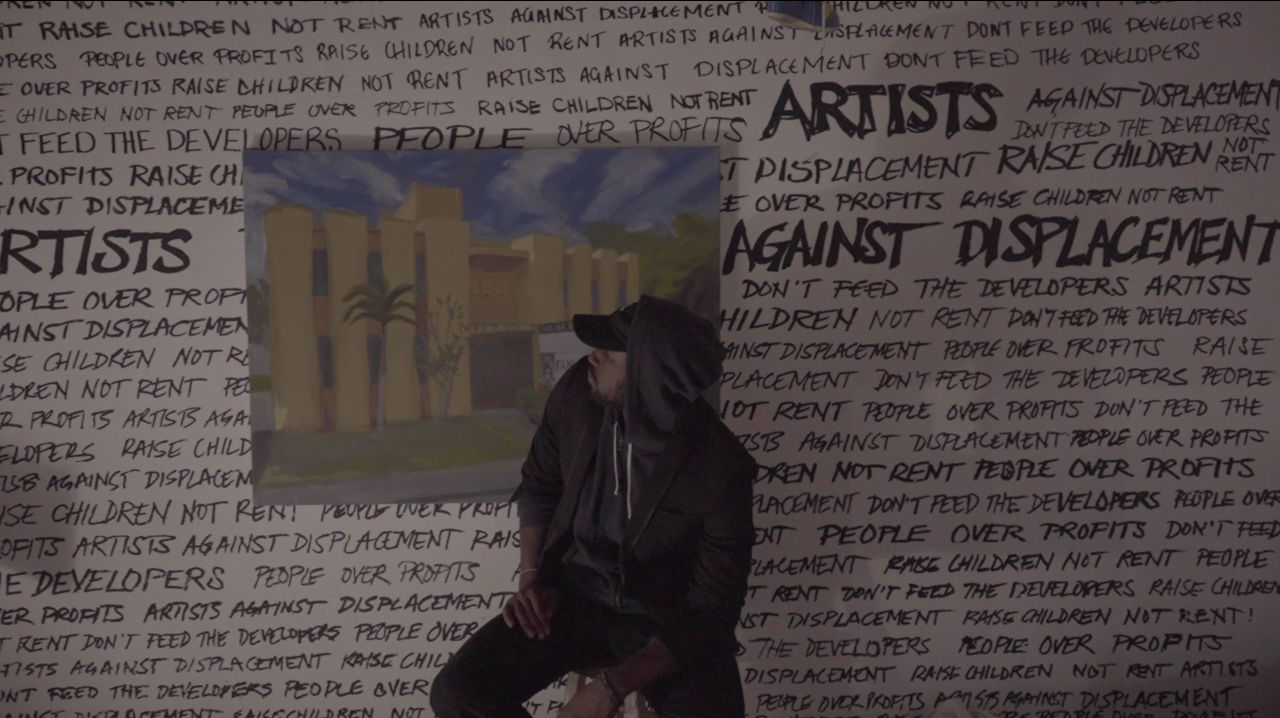

‘Where the Land is Free,’ an exhibition presented by VOICES: Poetry for the People from Cultured Magazine on Vimeo. Video by FXRBES.

This message courses through Where the Land Is Free, an exhibition presented by VOICES: Poetry for the People, on view at Wynwood’s Bakehouse Art Complex. Aja Monet—poet, activist, co-founder of VOICES and of Smoke Signals, a collective rooted in both art and community organizing—is showing me the space, the intricate work, the still-pulsing energy of its opening night. The room is full of voices and flowers—vines wrapped round columns, fake and dried blooms bursting through the door, soil circling a podium where poets spoke the week before. “Activists and poets have always known the impact of culture and language,” says Monet. “The assumption that art is void of intellectual power is a false narrative.”

Where the Land is Free has a few origin points—it was developed via open call, and the work is designed to draw attention not only to the artists, but to the surrounding neighborhood: Meet Your Neighbors, a piece by Calvin Early, is comprised of photographs of longtime black and brown Wynwood residents, framed with leaves, as if to rest on their laurels. (They were all invited to the show.) But first, it began with Smoke Signals, which is based in Monet’s—and her partner, Umi Selah’s—living room. Smoke Signals and the Dream Defenders intentionally built a collaboration with Community Justice Project (CJP)—a group of movement lawyers that provides legal support to organizers and grassroots groups to strengthen their ability to fundamentally change the conditions of their oppression.

Three years ago, residents in the Little Farm Mobile Home neighborhood were, explains Monet, “getting kicked out of their homes by developers. Community Justice Project works hard to represent marginalized folks. They were working with Spanish and Creole-speaking people who didn’t know how to fight back.” CJP asked Monet to help facilitate poetry workshops with neighborhood residents, believing that the power of language and expression could bolster their efforts. Monet adds: “Community Justice Project was a huge part of this even being possible. They facilitated all of the projects we’ve been able to create…As legal language looks to diminish and marginalize voices, poetry seeks to empower, encourage, and to offer counter narratives to the mainstream conversation. This group of lawyers sees the value in this.”

Developers moved in too quickly; they always do. But with CJP’s help, Smoke Signals received funding to continue their workshops, teaching organizers and neighborhood residents and young and old alike to share their voices, utilize them to fortify themselves. The project was named VOICES: Poetry for the People. “The first iteration of the workshop was grounding organizers, community activists and leaders in the history of poetry as part of activist movements,” explains Monet. “We read a lot of work from the Black Arts Movement, the Chicano Movement, the American Indian Movement. This is a legacy we’re following.”

The workshops led to last summer’s Maroon Poetry Festival, which featured “poets spitting fire,” beehives full of honey, guests like Emory Douglas of the Black Panthers; poet Ntozake Shange shared one of her last public readings before her passing last October. “We thought of poetry not just as writing a poem,” says Monet, “but as how we created space. How do we become more intentional about the nuance and depth we want people to come away with?”

By last fall, CJP had been working with Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood for over two years, often alongside organizations like Family Action Network Movement, to address the displacement that has become concurrent with the neighborhood’s swift development. As Meena Jagannath, co-founder of CJP, explains: “Given the realities of the heated struggles with Temporary Protected Status for Haitian immigrants and development impacting the neighborhood, we made a decision to further integrate Poetry for the People into our ongoing work, to try to move towards a paradigm where poetry was truly marshaled in service of people in struggle.” Poetry for the People attended community meetings with CJP, becoming more deeply entrenched in the work.

“We’re not against development,” says Monet. “We’re for development, but without displacing people. Institutionalize public housing, create community land trust and affordable housing, jobs. Before you even reach a conclusion, sit with the community and strategize. See what they need in a holistic, strategic way: These ideas became the heart of a lot of our meetings and poetry. If you give people another way to describe, imagine and envision something, you open up a whole scene for folks to get activated and mobilized for. That’s the goal: to let people know there are more possibilities. That it’s not too much to ask for the bare minimum.”

Artists aren’t exempt from these conversations—in fact, they’re often catalysts for the most dramatic neighborhood changes, utilized by developers as proof of a place’s value. Says Jagannath, “The orientation of Poetry for the People to issues of displacement comes from a recognition of the need for artists to accompany communities in the context of development and subsequent evictions.”

“We’re always thinking about how to create something alternative to what the art world has created,” Monet adds. “We see how artists are a big part of the displacement that’s happening. They’re strategic for the developers in this way. It’s happening everywhere. What we thought was, how do we get artists to be aware of this, and accountable to it?”

The work in Where the Land is Free, that room of flowers, addresses this and more: The slow destruction of the planet. Prison reform (on opening night, Brian Harrington, a workshop participant’s partner, still incarcerated for a crime committed as a child, read his own poetry aloud over the phone). The exhibition recalls not simply new beginnings, but who was here first. The soil. Indigenous communities. Longtime neighborhood residents, often fighting for their homes, the history contained therein. It argues—tenderly—for a new way to map the country’s rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, one that considers their people as strong, embedded roots—immovable, unmoored.

VOICES: Poetry For The People | Where The Land Is Free is on view at Bakehouse Art Complex through June 2019.

in your life?

in your life?