When Mel Chin began preparing for this month’s solo show at the Queens Museum, which is co-presented with No Longer Empty, the artist’s mind was on Flint, Michigan. A frequent visitor to the former industry capital thanks to his Fundred Dollar Bill Project— a participatory initiative the artist launched in 2006 aimed at drawing attention to preventable lead poisoning—Chin bore witness to a full-scale water crisis fading from the headlines and subsequently the public’s consciousness.

Moved by the efforts he saw on the ground, Chin decided to use his survey show as a platform to harness the energy and materials on hand— namely thousands of plastic water bottles.

Working with N.E.W. Life Center, a nonprofit where local residents operate a commercial sewing business as a job-training outlet and source of steady employment, and Unifi Inc., a company that transforms plastic bottles into a polymer suitable for fabric, he was left with one important position to fill—a design partner. He found that in fashion designer Tracy Reese. Nine looks and one museum show later, here the Flint Fit duo discuss the project in their own words.

Tracy Reese: I’d never been approached by an artist before, and when Mel came in with a team from Queens Museum to discuss the water crisis and what his goal was, I knew that I had to participate. I loved meeting him and hearing his vision, but being from Detroit myself—so close to Flint—it made the issue even more real.

People are still drinking out of water bottles and we don’t read about that anymore. The idea here is to make people understand that the struggle is ongoing by expressing that creatively. And hopefully it will be uplifting for the community in Flint, as well as those who come to the show.

Mel Chin: The most essential thing for this project was to have it all come together—from weavers in North Carolina to the design in New York to the people of Flint. I think that’s part of this project’s poetics. In the end, Tracy was able to create nine looks that really spoke to this unity.

TR: Every designer is different, but I think for this particular project it had to start with the fabric. As soon as we got a selection of swatches of what could be made, I edited those down to two different qualities. One is a cotton-blend twill. The second is a jersey fabric that’s 100 percent made from the bottles.

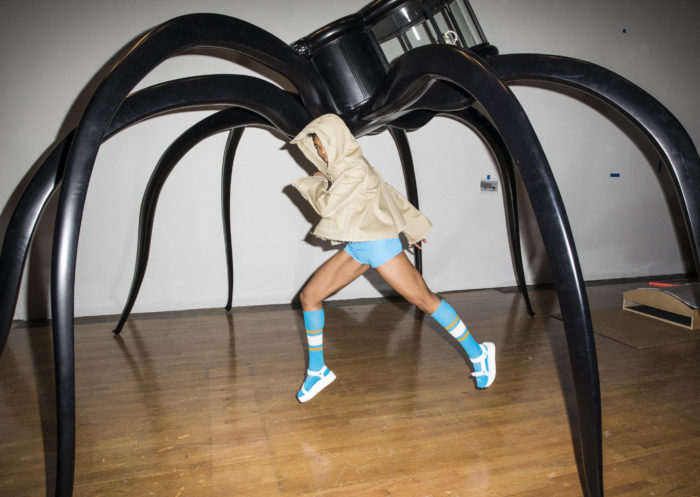

I focused on rainwear first because the twill I thought really lent itself to that. Raincoats and trench coats, and they’re protective as well. I feel like there’s a need for protection, for the people of Flint. Then juxtaposing that was swimwear, which was what we made from the polyester knit fabric. Again, it all goes back to water use.

MC: In fact, once we had approval and the weavers, we were able to fill a whole tractor trailer full of bottles in a matter of weeks, which I think was a testament to everyone’s investment. Projects like this absolutely require a relationship with communities. Flint Fit came together because of a team effort, not because I’m some artist who’s thinking up stuff. I’m grateful to all that. I’m grateful to meet the citizens. I’m especially grateful to Tracy and that original amazing yes.

TR: Thank you, Mel! I think it’s more and more urgent we work together. In the past year or so, I’ve been trying to personally start addressing all the pollution that fashion causes. My goal within the next year is to completely overhaul how we do business and the type of designs that I’m creating and how they’re being produced. We’ve never produced fast fashion and I’m not that kind of designer. I talk to customers and they’re like, “That dress is my favorite and I have worn it for 10 years.” Those are the kind of clothes that I always aspire to make.

I don’t believe in over-consumption, I don’t believe in creating really inexpensive things that are such an insult to the people who are forced to make them and the environment as well. I’m all for slow fashion and appreciation of the workers. I think Americans have a romance right now with cheap stuff. It’s not a direction that we can afford to continue moving in because it’s really harmful for the planet. So recycle, reuse, renew: those are three words that I, as a designer, want to be living by. We also need to educate the public.

MC: Of course, education is not simply about launching a new project, it’s about continuing critical assessment. I’m already into trying to see if this prototype can go further. I’m looking into filtration devices and other things you can do.

When you’re talking about responsibility, it’s not just one thing and it’s done. It’s about establishing new habits and histories.

TR: Exactly. When I was beginning to think about the project I did a little research on the city of Flint itself, and the heyday of Flint was really in the early days of the auto industry, when they had quite a few plants and executives.

I really love the early part of the 20th century for design inspiration and thought it would be a good place to start when examining this watershed moment, where an industrial town was transformed into something else.

MC: I love the idea that if this fabric, this idea, takes off, that it could bring back some of the manufacturing energy to Flint. It’s about rekindling the possibilities.

TR: Like I said, I’ve been exploring ways to incorporate more recycled materials into my work, so this is such a good starting place for me to really work with recycled materials and not just use them, but work with their properties and try to bring out their own duties.

MC: We also thought about this when putting together how the garments would be displayed at the museum. I’m opting for the mannequins to be put into motion so they could be like the audience itself looking at the watershed, inspecting a bottle, sitting at a table, looking at Tracy’s drawings or walking. I want to make a connection between people and the garments themselves.

TR: Yes, exactly. There will be a presentation with models as well. It’s all part of the learning curve.

MC: I consider Tracy as a co-artist. Concept is one thing, but having a person like Tracy being an artist with me, that’s the joy. It makes you happy.

TR: Mel too. His vision is so clear and I think he’s really holding the people of Flint central to this project. I think that that’s been incredibly important. I think it’s both of our responsibility to make sure that this is really all about them and their struggle and hopefully their overcoming.

MC: Absolutely. When you hear some of the statements that come out, most of the time people don’t really help those that are struggling. In the larger context of the world, and regardless of the political climate, nothing has ever been as challenging as overcoming this apathy. I often say I’m not inspired by these situations, but I am compelled by these situations to do my job and try to creatively come up with options that didn’t exist before.

I’ve been compelled by the strength as well as the struggle of the people of Flint. They have gone through thousands of days without clean drinking water. That’s something to think about.

in your life?

in your life?