These are hard times for high culture. In the music world especially, venerable institutions like New York’s Metropolitan Opera have been struggling with aging audiences, while symphony orchestras from Fort Worth to Philadelphia have been beset by labor disputes and financial shortfalls. But it isn’t all bad news: lovers of classical and modern orchestral music can point to a pattern of growth in select cities, especially overseas, that have stepped in with both fiscal and moral support for their hometown venues. And where the civic will has found a way, the best and most high-profile way has been to remake the venues altogether, leading to a modest boom in new concert halls around the world.

In China, the pace of construction has been especially brisk, with spectacular new auditoriums popping up in fast-growing second-tier cities, such as Harbin. Two years ago, the metropolis debuted an ultra-modern opera house by Beijing-based studio MAD Architects. The same firm will now be bringing the boom back to the capital: under the stewardship of founder Ma Yansong, MAD has just begun construction of the new China Philharmonic, an enigmatic whirl of gauzy, translucent glass. The site, wedged into a traffic-bound corner lot next to the 1950s Workers Stadium, posed a challenge; but the firm has a knack for these kinds of tricky situations—only a few blocks away, their recently completed Chaoyang Park Plaza commercial development is an oasis of organicism amid the Beijing bustle. The concert hall design takes a similar tack, with lush landscaped gardens surrounding the shimmering form in order to “visually disconnect it,” as Yansong puts it, from its urban environment. “The idea is to create the sense of being in a different place, right within the city center,” he says.

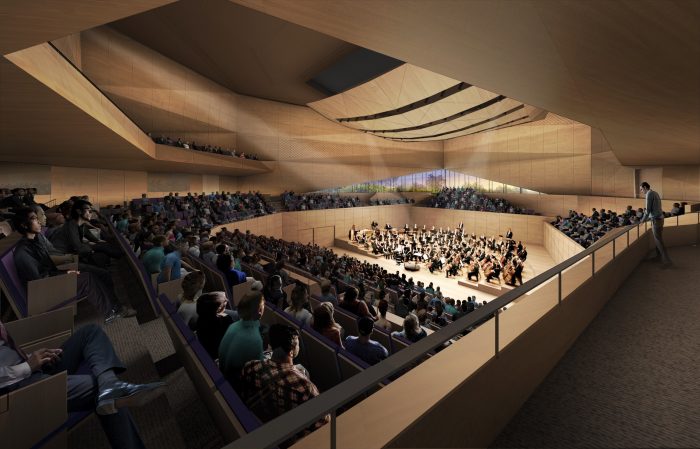

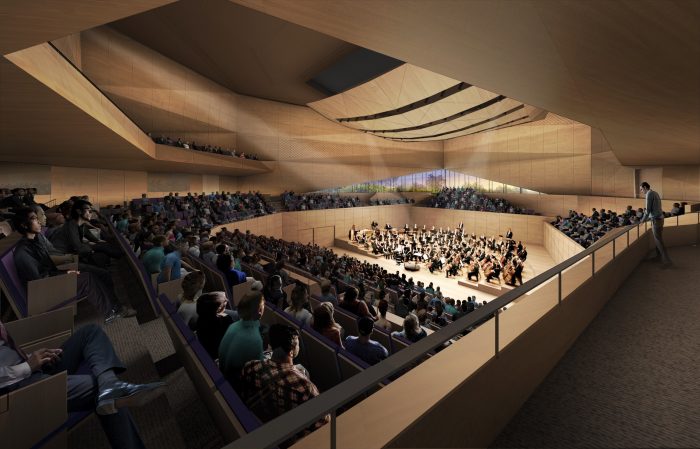

In a radically different, if no less improbable context, Swiss master builders (and 2001 Pritzker Prize winners) Herzog & de Meuron have lately put the finishing touches on their design for the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, Germany, home to the city’s famed radio orchestra. Sitting on a slender peninsula in the middle of a sometime shipping district, it blends in neatly with the rough-and-tumble setting, with a lower eight- story block consisting of a converted brick warehouse. Above that, the designers have mounted a bold sculptural crown, twice as high the base, faced entirely in glass and topped with a curving outline recalling waves or a billowing sail. Given the maritime locale, the reference is relevant, and despite considerable delays and cost overruns the project has quickly endeared itself to the citizenry, who’ve dubbed it the “Elbie.” The European affection for live music, and for the buildings that host it, is of course a longstanding continental tradition, woven into the fabric of its cities; yet the main drivers of new concert hall construction are fast-growing urban centers in the developing world who desire to firm up their global status. Hence the dominance of East Asia. Two more venues in the region seek to put their up-and-coming hometowns on the cultural map: the Taipei Performing Arts Center, from Dutch firm OMA and its superstar cofounder Rem Koolhaas, and the theater component of the new campus of the Juilliard School in Tianjin, China, by New York–based office Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The OMA building is (in the words of the architects) an “experimentation in the internal workings of the theater”— a multi-stage, completely adaptable theatrical environment that can be reworked for productions of all scales, even scales never attempted before, all contained in a novel envelope featuring a protruding street- front sphere. More tranquil, if no less innovative, is DS+R’s performing arts facility, the first outpost aboard for the storied New York City institution: Embedded within a folded, complex geometrical volume, the music hall interior lifts up at one corner to reveal the greenery and riverfront views beyond.

China’s relative dominance in the concert-hall arms race doesn’t mean the U.S. has been entirely left out. In New York, the long-awaited arts component of the new World Trade Center complex is finally underway: REX Architecture’s Ronald O. Perelman Performing Arts Center, named for the benefactor whose gift last year of $75 million helped kickstart construction. Located on the site of a temporary train station, the building is a stately block with a marble-clad façade, the stone paneling carefully book-matched to create a beguiling patina. More important, however, is what’s inside. “Arts buildings are increasingly challenged to be multi-use,” REX principal Joshua Prince- Ramus explains. “The Perelman can create exceptional conditions for all the major performing art forms within a single structure”—a flexibility facilitated by three auditoria which can be combined and recombined into nearly a dozen different configurations.

So what ties together the current crop of high-brow concert destinations? Given the challenging climate, the necessary formula would appear to be a mix of functional adaptability (throwing music together with other genres of performance for mutual support), inventive siting (with a special focus on formerly neglected or fast- changing pockets of the city) and, by far the most crucial element, a sense of municipal mission—a shared sentiment between donors, citizens and government that music is a crucial part of the history and future of their city. With those factors in place, the architectural sky would appear to be the limit, as architects and their clients bet on ever-more inventive designs to keep the crowds coming and keep live music alive in the 21st century.

in your life?

in your life?