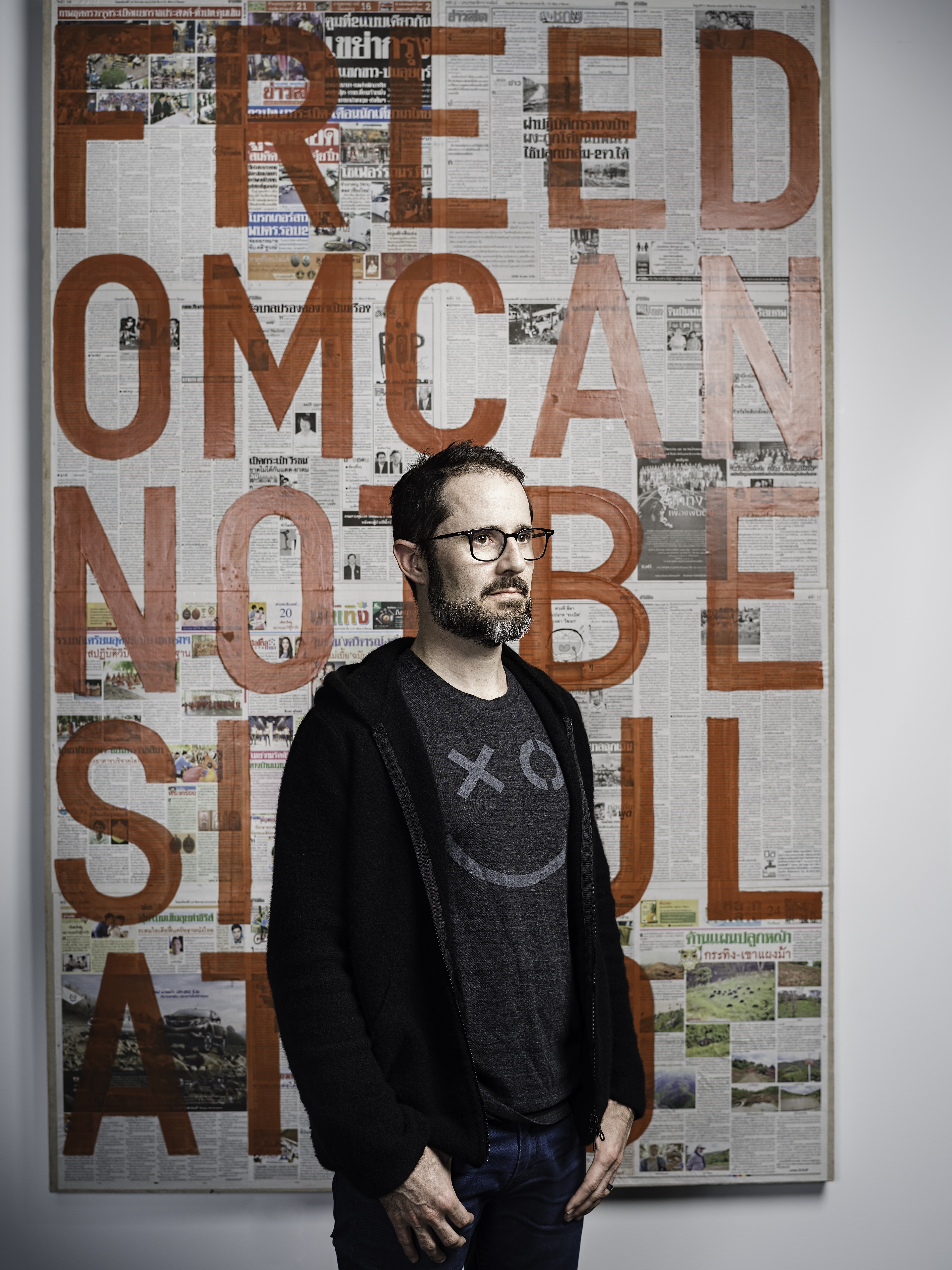

On the dancefloor at a recent Silicon Valley wedding, most of the techies demonstrated an endearing lack of rhythm or clumsy Burning Man dance moves. But Evan Williams, co-founder of Twitter and founder of Medium, was as light on his feet as a late-1970s Soul Train extra. Williams is not your average tech billionaire. He didn’t go to Stanford or Harvard. Indeed, he is mostly self-taught and has an honorary doctorate in journalism from the University of Nebraska. As a high school sophomore in rural Nebraska, he took mandatory basic programming. “It made so much sense. I could make things and I was good at it,” explains Williams. “It was like painting a picture and solving a puzzle at the same time.”

Williams is so urbane that it is hard to fathom that he started life on a large corn farm, four miles away from a town with no stop light. The family culture included three TV channels, subscriptions to specialty farming magazines and church on Sunday (out of social obligation rather than religious conviction). Although the young Williams was not into school, he loved reading. Starting with library books about juggling and breakdancing, then biographies of Benjamin Franklin and Babe Ruth, Williams moved on to titles like How to Get Rich in Real Estate and an eccentric succession of business titles. “Once I understood that I could learn things from books that people around me didn’t know,” explains Williams, “I had a great secret and source of power.”

Reading, writing and the communities generated through words are integral to all three of Williams’ startups. “Ev is one of the legendary product people. He is the king of the blog,” says Ben Horowitz of the venture capital firm, Andreeson Horowitz. Williams’s first company Blogger, which popularized the term, made it easy for anyone to share their thoughts via the internet. “Blogger exhibited the virtue of great innovation—simplicity. It changed everything. It opened the way to self-publishing online,” declares Walter Isaacson, CEO of the Aspen Institute and author of “Steve Jobs”.

Selling to Google for an undisclosed sum in 2003, Blogger was the tech giant’s very first acquisition. “I didn’t feel like I was one of the clan,” says Williams, about becoming a Googler. “But I look back on it fondly. It was genuine—the ‘Don’t be Evil’ thing.” Williams worked at Google for 20 months, leaving shortly after the private search firm went public. With his newfound wealth, Williams became the lead investor in his next company, which led to Twitter.

The history and in-fighting of Twitter is well documented. “It was fun,” says Williams about their early success. “Communicating through the phone was new. Twitter was very simple. It had a good name.” Williams still sits on the Board and owns about 4 percent of the company, but he endured the painful experience of being fired as CEO in 2010. “I am very lucky and grateful to have been a part of Twitter. It will always be a part of who I am. I will always care and always be frustrated,” he says. How does Williams feel about Jack Dorsey, his co-founder and Twitter’s current CEO? “Jack works really hard and is very committed to doing the right thing,” says Williams. “Once in a while, we go for drinks. It’s like we have a shared child, but he has custody.”

Twitter’s 140-character format changed the pace of communications and is now the main forum for political banter in the USA, UK and Japan. (Ever a fan of miniaturization, Japan has the highest per capita usage of Twitter in the world.) Last year, Williams told The New York Times that, if it were true that Donald Trump wouldn’t be President without Twitter, then he was sorry. “In Twitter’s early days, our equation was ‘More speech = good.’ We were pretty naïve,” he admits. When asked about the rogue Twitter employee who shut off Trump’s account last November, Williams stares at me with a poker face and says, “No Comment.” His eyes start to sparkle and then he allows himself to guffaw.

Williams is restrained and reflective—not in the slightest bit twittery or impulsive. Ask anyone about his character and the first adjective out of their mouth is “thoughtful.” “Ev can be very quiet, but it’s because he is taking it in. He’s thinking,” says Judith Estrin, a serial entrepreneur who once sat on Williams’s Board.

Medium, a publishing platform focused on long-form writing, appears to reflect Williams’s temperament much more than Twitter. Its name suggests an even-keeled, impartial vehicle or a spiritual channel of not-yet-dead investigative journalist values. “There is more and more superficial crap and it is harder and harder to find depth. What’s going to fix that?” asks Williams.

Now five years old, Medium’s goal is to spread “ideas and stories that matter” through technology rather than editorial fuss. Among Medium’s 80 employees, only about half a dozen “touch the content” through “curation” and partnerships with publishers. Williams predicts a massive consolidation of online writing in the same way that YouTube and subscription services like Netflix and Amazon Prime have aggregated video.

“Why does every writer or publisher in the world need their own website?” he asks.

While most of Medium’s content is free, a subscription of $50 a year gives readers access to exclusive and syndicated content from The Economist, MIT Review, Samantha Bee’s Full Frontal, etc. “Advertising-driven online media are a dark, distorting force,” declares Williams. “Web ads do not pay for quality. Reality TV and BuzzFeed amount to the same thing— cheap content. We want to enable writing that makes people smarter and deepens their understanding.”

Clearly, Williams is motivated to make the internet a better place and perhaps make amends for the “twittification” of American culture, but one wonders: how does he maintain his energy for yet another entrepreneurial venture?

“My father was an ambitious farmer,” he explains. “He worked with 5,000 acres of farmland, which he was always trying to expand. He would fix and invent machinery with junk and odd parts, welding in the woodshop.”

Through paternal inheritance, Williams is clearly independent and persistent; he thinks long-term and from first principles. Moreover, he’s a businessman who finds deep satisfaction in the creative process or “defining what you are building,” as he puts it. Like computer programming, running a tech company requires a certain addiction to problem-solving. “What if it could be this? Okay, how do we make it do that?” asks Williams. “Tackling these kinds of questions is the easiest thing I have ever done to get into the flow.”

in your life?

in your life?