Renowned in the realm of architecture but hardly a household name, Pierre Chareau is celebrated in France as the architect and interior designer who collaborated on the legendary Maison de Verre, one of Paris’ hidden treasures.

“No house in France better reflects the magical promise of 20th-century architecture than the Maison de Verre,” then architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote in an August 2007 New York Times article, after having spent a few days in the enchanting Left Bank abode.

Begun in 1928 and completed four years later, it has become one of the most influential works of modern architecture despite the fact that very few people have actually seen it. A cult classic, the House of Glass (as it’s translated in English) remained hidden in a chic Paris neighborhood until it was bought and restored in 2006 by Robert Rubin, a Wall Street-trader-turned-architecture-aficionado.

American audiences now have the chance to learn more about the dynamic house as well as Chareau’s imaginative interior design, rarely seen examples of his furniture and lighting, his designs for the film industry, and his other distinctive architectural projects in the exhibition “Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design” at the Jewish Museum in New York through March 26, 2017.

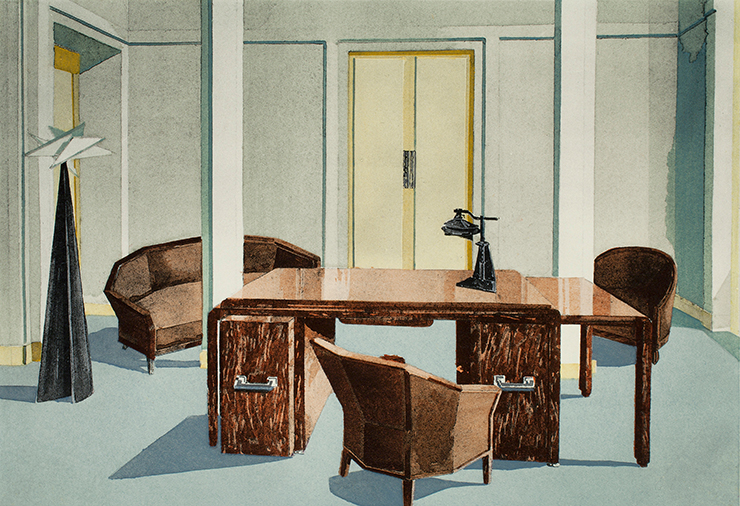

Born in 1883 in Bordeaux, France, Chareau failed his entrance exams at the eminent École des Beaux-Arts in Paris before taking a job at a Paris-based British furniture manufacturer, rising from an apprentice to head designer. Serving in a French artillery unit during World War I, he started pursuing his own projects toward the war’s end. Eventually he designed a study and bedroom for his friend Dr. Jean Dalsace, who would later commission the Maison de Verre.

Designing modern furniture, which was characterized by his innovative use of wood and metal, and doing interior design work for well-heeled clients, Chareau soon joined the prestigious Société des Artistes Décorateurs. In the mid 1920s he opened two Parisian retail locations: a shop on the Left Bank, where he sold cushions and hand-throws, and a showroom on the Right Bank, which carried his furniture and lighting designs.

A visionary designer, Chareau lent his expertise to the world of cinema, as well. He collaborated with modernist architect Robert Mallet-Stevens to create furniture for three of French film director Marcel L’Herbier’s movies and designed the stage sets for Edmond Fleg’s production of Merchant of Paris at the Comédie Française in 1929.

Even before he began designing the Maison de Verre, Chareau and his wife, Dollie, collected Modern art and hosted salons for the celebrated artists, writers and musicians of the day. Once it was complete, the Maison de Verre also became a hotbed of intellectual activity. Social events added to the house’s fame and were attended by creative types such as Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard and André Breton.

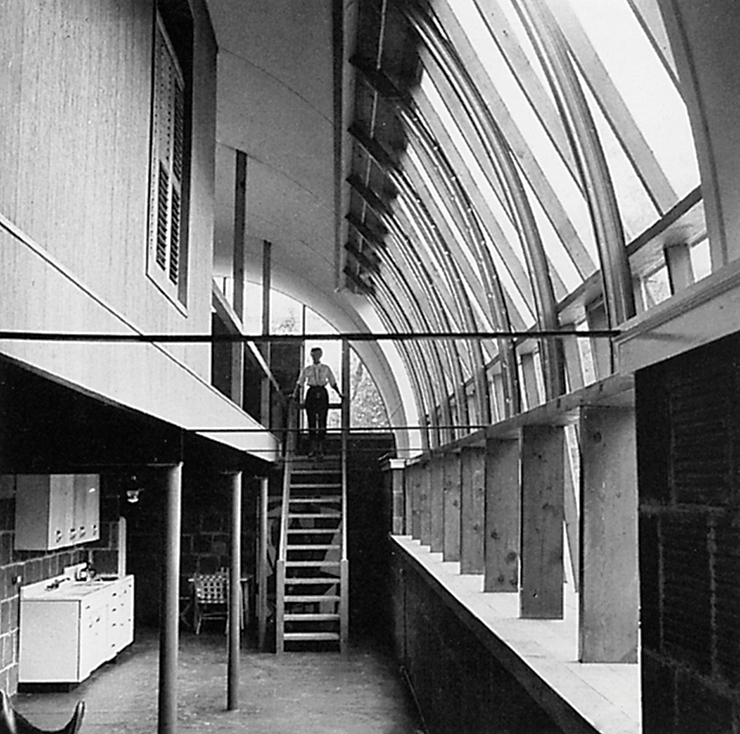

But it was Chareau’s imaginative design of Jean and Annie Dalsace’s house that got everyone talking. Constructed with glass and steel in a three-story space carved underneath an existing 18th-century building, the Maison de Verre housed Jean’s medical practice and later functioned as a guest house for friends.

The façade of the building consists of translucent glass blocks in a steel grid. Steel staircases, perforated metal panels and mechanical details lend an industrial, factory-like feel to certain sections of the house, while the hidden upstairs study and ship’s ladder connecting a boudoir and bedroom provide a sense of retreat from the surrounding urban environment.

The Jewish Museum exhibition, which was curated by Esther da Costa Meyer, a professor of the history of modern architecture at Princeton University, and designed by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro—famous for their designs for The High Line in New York and The Broad in Los Angeles—features a selection of the designer’s objects, drawings and photographs of his adventurous projects and avant-garde artworks that were formerly in the couple’s collection.

Forced to flee France when the Nazis occupied Paris, Chareau and his wife migrated to New York in the 1940s. In 1946, he designed a house in the Hamptons for the Abstract Expressionist artist Robert Motherwell. Resembling a Quonset hut, the design was radical for its time. and it was showcased in a Harper’s Bazaar article in 1948. Unfortunately, the press didn’t help to create more work for the designer in America, which made the Motherwell House (demolished in 1985) Chareau’s only important project outside of France.

Afterward, the Chareaus got by with Dollie giving cooking lessons to wealthy Americans and from selling off art from their collection, including a precious Amedeo Modigliani sculpture to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In the 1950s, the designer sought a show at MoMA, but Philip Johnson, the museum’s director of architecture and a staunch supporter of Chareau’s rival Le Corbusier, rejected the idea—perhaps because he had just built his own Glass House. Downtrodden, Chareau died later that year.

It would take another generation for his prominence to return, with Richard Rogers, one of the architects (with Renzo Piano) of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and Jean Nouvel, architect for Paris’ Institut du Monde Arabe and New York’s 53W53 (originally named the Tour de Verre), both identifying the Maison de Verre as a major influence. Now, this exhibition should help make Chareau’s sophisticated designs more recognizable across the pond.

in your life?

in your life?