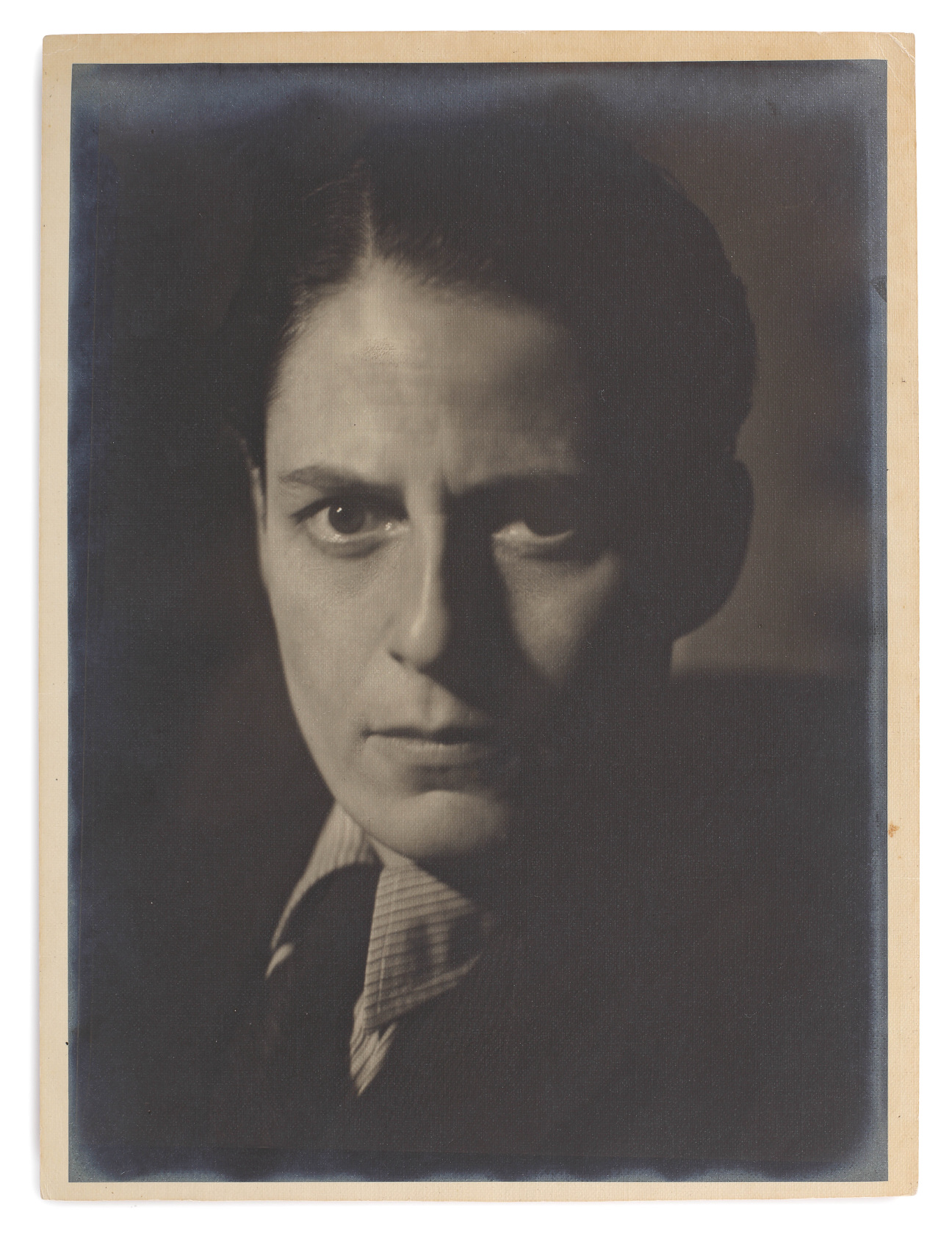

“Professionally known as GLUCK, without prefix or initial.”

This is how the still-too-little known painter, born Hannah Gluckstein, introduced themselves in their 1957 submission to “Who’s Who,” a compendium of influential British people. Born in 1895 to a wealthy Jewish family in the catering business, Gluck became mononymous in their 20s, adopting a uniform of tailored suits and close-cropped hair; they insisted on exhibiting only in solo shows. When an arts organization addressed them as “Miss Gluck” in a letter, they promptly resigned as its vice president.

Gluck, who died in 1978, is one of eight artists in “The Laughing Torso,” a lively presentation by Marlborough gallery at Frieze Masters in London this week. Each featured individual chose to adopt male or gender neutral names in lieu of their female birth names. In literature, the nom de plume is a well documented tactic for women looking to circumvent a sexist publishing industry (think George Eliot or J.K. Rowling). Visual artists, meanwhile, have deployed the technique for a variety of purposes, from the professional to the political to the personal.

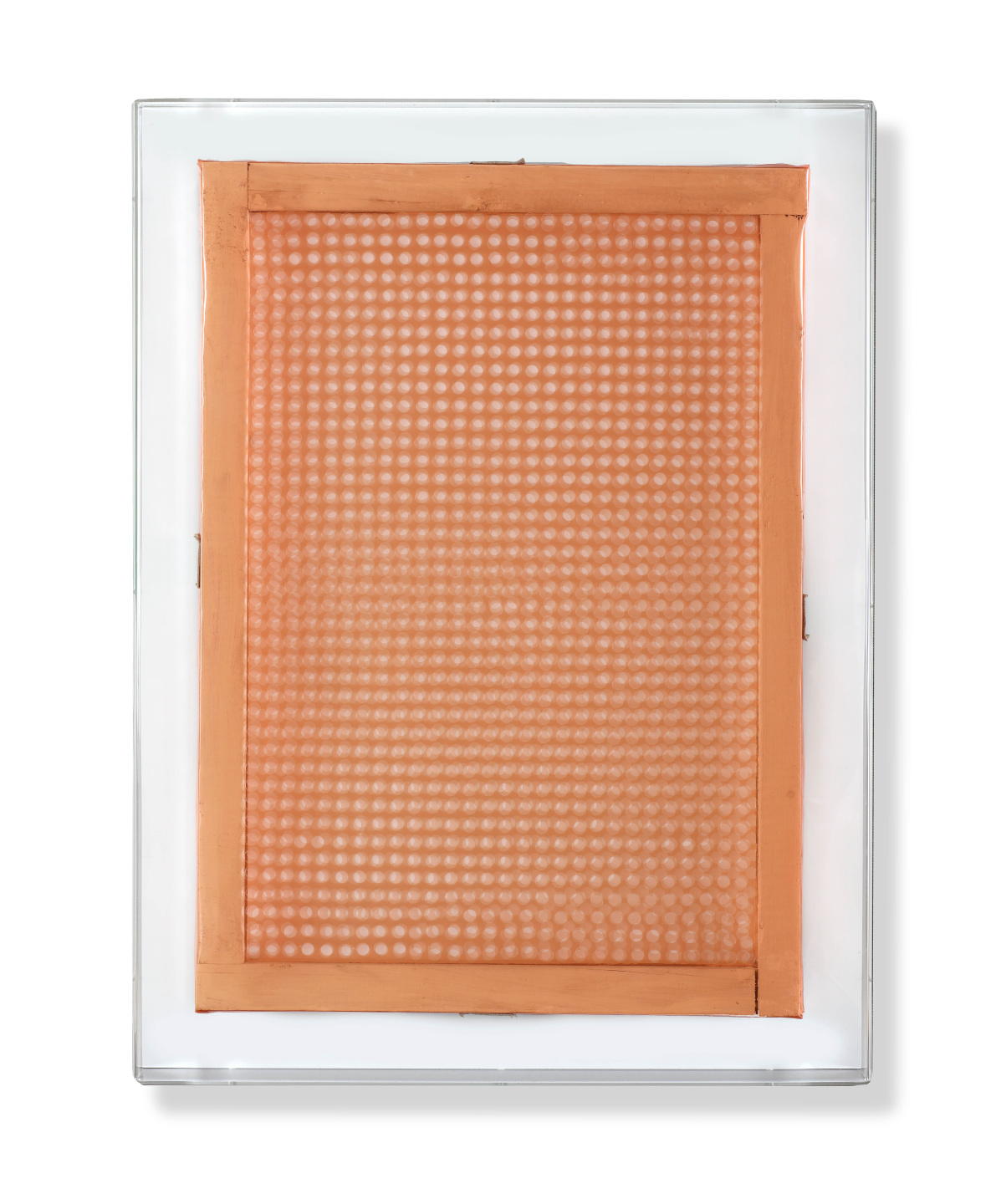

Consider the Italian artist Dadamaino (born Eduarda Emilia Maino in 1930), a contemporary of Lucio Fontana who adopted a new name to express her devotion to avant-garde thinking. She would go on to create an entirely abstract alphabet, which she considered a new visual language to give voice to the oppressed. There is also the Dutch abstract painter and textile designer Nicolaas Warb (1906-1957), who changed her name from Sophie Warburg during World War II to guard against both sexism and anti-semitism in Nazi-occupied France. (Claude Cahun, who, alongside her partner Marcel Moore, produced genderfluid portraits of various personae that inspired Cindy Sherman, was originally supposed to be included, but the works were left out at the last minute due to condition issues.)

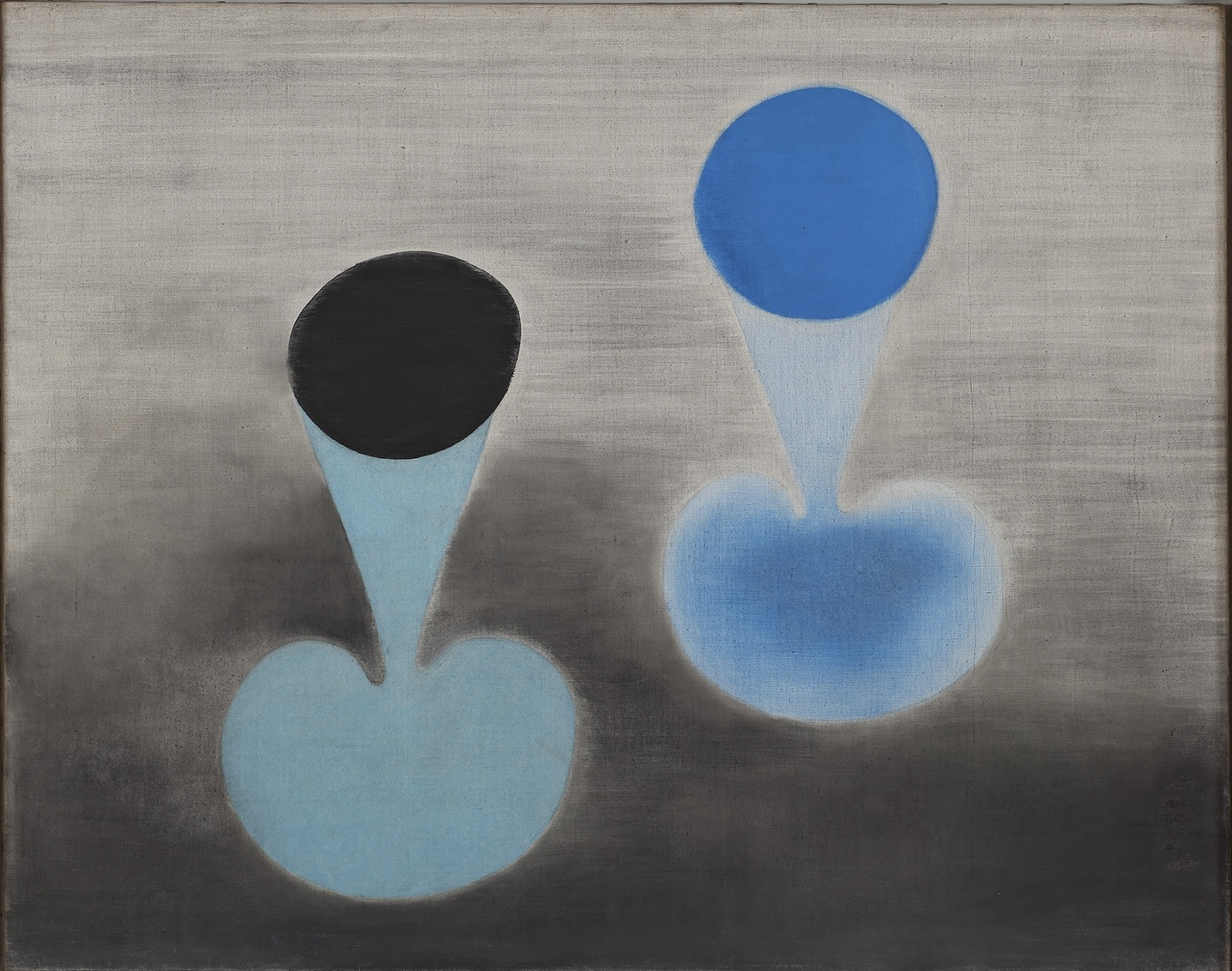

When asked if changing their names actually helped these artists achieve professional success, art historian Anke Kempkes, who organized the presentation, was ambivalent. In the tight-knit avant-garde art worlds of London or Paris, the measure was less of a ruse than an opportunity to spin or refashion one’s identity. In the years between the World Wars, gender experimentation was regarded by some as a sign of modernity. At the same time, “abstraction was considered the most male-dominated form,” says Kempkes. “There was an idea that women couldn’t even think abstractly.”

Many of these artists enjoyed professional success during their lifetimes, but faded from prominence later in the 20th century for reasons that have become familiar: They were written out of mainstream histories, lacked the support of galleries or the advocacy of wealthy patrons. But there were other factors at play, too. The contents of the French studio of Marlow Moss, an androgynous Constructivist painter who dressed, as Kempkes put it, “like an English country gent,” were destroyed in a bombing during World War II. (Several surviving geometric drawings are on view at Frieze Masters.) Piet Mondrian is said to have borrowed at least one of Moss’s ideas without proper credit.

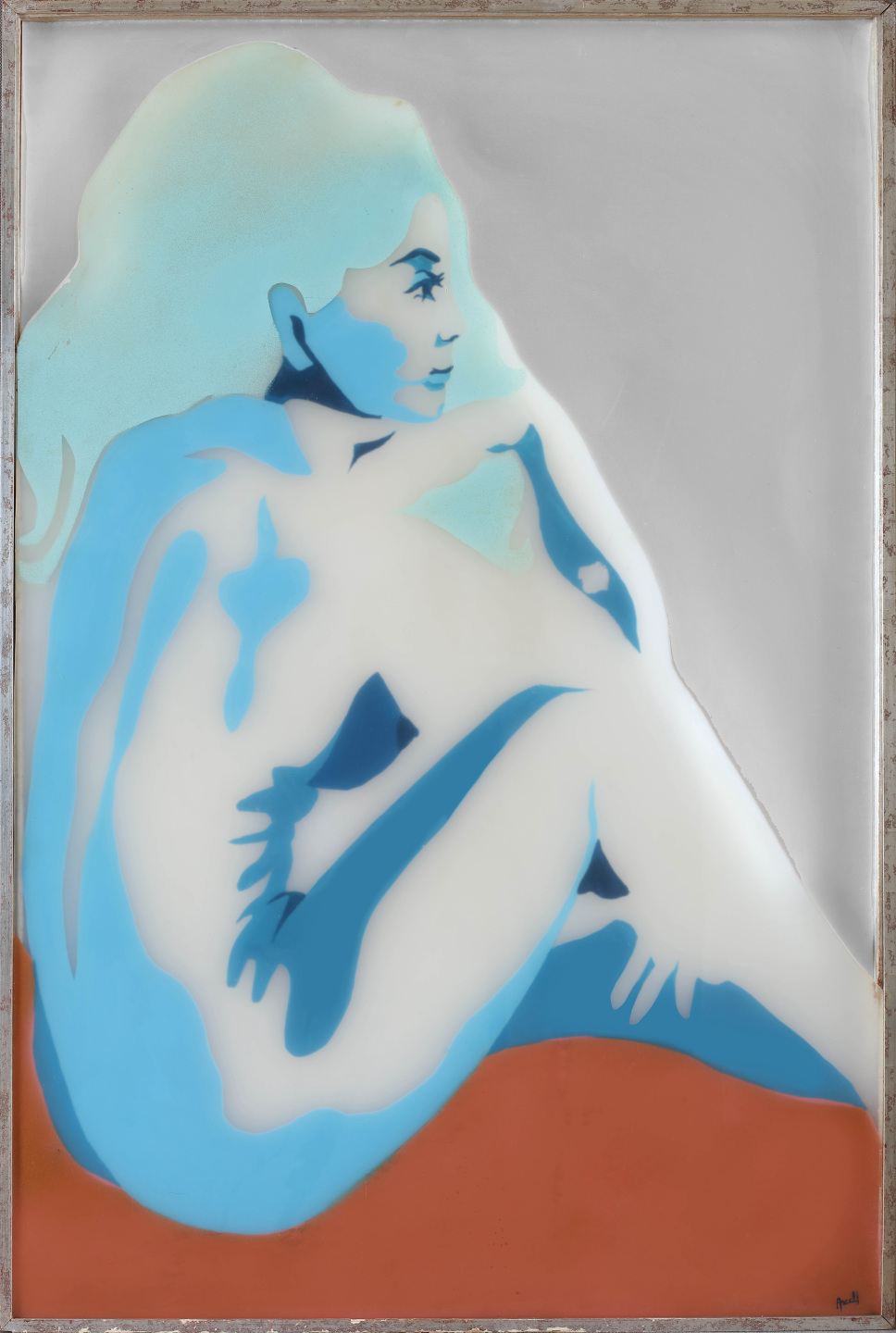

Works on the Frieze Masters stand, which also include heavily impastoed and layered paintings by American Abstract Expressionist Michael West (born Corinne Michelle) and painted wood reliefs by the influential British surrealist Paule Vézelay (born Marjorie Watson-Williams), range from £6,500 for photographs to £350,000 for large paintings, according to the gallery. A representative declined to say whether anything had sold. Kempkes estimates that two-thirds of the objects are for sale while a third are loans.

Many of the artists on view have enjoyed a new wave of interest at a time when gender norms are again being expanded, toyed with, and disassembled. The gallery has been positively “stormed” by demand for Gluck, according to Kempkes. Young audiences in particular are drawn, she says, to the notion that identity can be refashioned in its own kind of artistic expression. Or, as Moss put it 1955, “I destroyed my old personality and created a new one.”

in your life?

in your life?