Yewande Komolafe believes cooking is both an art and a science. The daughter of a food scientist, she studied biochemistry before becoming a pastry chef. Since then, she has served in almost every role in the culinary world, from line cook to food photographer to restaurant consultant.

This fall, she released her first cookbook, My Everyday Lagos, which seeks to capture the dynamic cuisine of the city where she grew up. CULTURED spoke with Komolafe about the wonders of red palm oil, the whitewashing of recipes, and why having children has made her more dynamic in the kitchen.

Where are you and what's in your system?

I am in Brooklyn. I just had a cheeseburger and fries because I was craving that. For breakfast, I hopped around. I had a boiled egg. I had a cappuccino. I defrosted one of Bạn Bè’s pandan coconut waffles that I had saved. And I had a huge glass of orange juice with a shot of ginger.

Your debut cookbook, My Everyday Lagos, was released earlier this fall. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

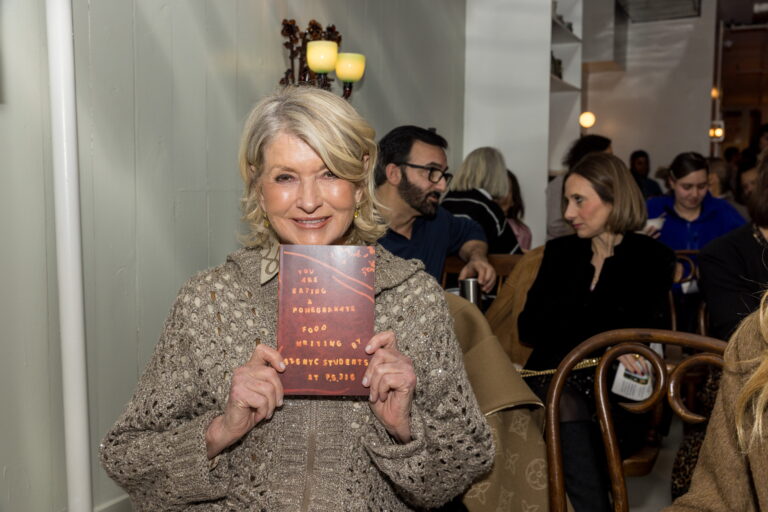

It felt like this huge secret that I was keeping for so long. It's a bit surreal to see other people holding it, but it also feels really good. While I was in Lagos, a lot of people had just bought the book and were talking to me about things they had read. It felt like this full-circle moment—something that started there and [that] I completed by bringing it back home.

Your mom was a food scientist. How did her approach to food shape the way you thought about it growing up?

I came to food through science first. I went to college for biochemistry. I thought that by going to culinary school, I was going to flex my creative side and get away from the structure of science. But I was a pastry cook, so it was all very structured and recipe-based. I like messing with the boundaries, but to do that, I have to understand what the structure is. I come to food from a place of trying to understand the ingredients—how much I can push them, and in what direction.

You have parallel practices of writing and recipe developing. How do you divide your time and think about these two spheres?

To me, a recipe is a narrative, so it doesn't feel too different from writing about it. In my recipe development, I'm just letting the ingredients tell me the story. And then in my writing, I'm repeating what the ingredients have told me. I'm narrating an experience that I had.

You've been a pastry chef, a line cook, a restaurant consultant, a kitchen assistant, and a food photographer. Is there any kind of work with food that you haven't done but would love to?

I want to travel more. As a writer for The New York Times, I view my work as journalism, and I want to go where the stories are. I want to meet people where they're at. If there's someone doing something very interesting with chocolates or truffles in Lagos, Nigeria, I want to go talk to them.

You didn't plan to write My Everyday Lagos. You published an article called “10 Essential Nigerian Recipes” in the Times and publishers approached you. Can you tell me a bit about how you made the project your own?

Working in food media, I've seen a lot written about Africa but I had rarely seen stories by Africans for Africans. When I got the book [deal], I was determined to tell the story directly to people who looked like me and to people who could relate to the subject matter without me having to explain. It's a pet peeve of mine, having to explain myself. I had gotten to this place where I was like, “I'm supposed to be here. I'm not going to explain my presence.”

Also, I was fresh off of a trip to Lagos, and I was determined to bring its energy into the pages of the book. Publishers are really good at making cookbooks and there's a structure in place, but I don't know that any of those structures had ever considered a place like Lagos in cookbook form. So I knew I would have to create a structure that would fit the story that I was trying to tell. I did that.

What does it mean to translate Lagos’s energy into the book? What elements were key in making that happen?

The book opens up with beautiful photography of Lagos and the water and the marketplace. You're immediately drawn into this world that has a lot of vibrancy. It could seem like a lot of noise, but once you focus on the words, it feels like that noise is just part of the experience.

Even the way the recipes are written—it starts with the story before you even know what you're cooking. Little things, like how the book is arranged from morning time through midday to evening through the weekend. It's almost like you're spending an entire week in the city.

In an interview, you said, “In addition to trying to figure out what home looks like, I think I'm also in the process of gathering the many selves that I have all around that I'd left in different places and telling them, ‘Come back now.’” The question of homecoming is very central to My Everyday Lagos and to a lot of your work. What ingredients make you feel most at home today?

I've been cooking so much West African yam. I've been able to find it here in different markets in Brooklyn, and there's a sense of calm when I start my day with some boiled yam, some Ata Dindin, and some egg. I also really love pepper soup during this season. It's so nice and thin, and there's so much flavor in each bite that it just reminds me of home.

In the summer of 2020, you and Priya Krishna had a conversation about whitewashing in recipe writing. How did you take those dynamics into account when you were developing My Everyday Lagos?

That's a question that is constantly on my mind because I think that food media here is very used to pandering to the white audience and it feels like the white audience is the only audience. In My Everyday Lagos, I resisted that by just not providing substitutions. Thankfully, we live in a time when I've been able to find Nigerian ingredients either on the Internet or just by going around to my neighborhood African grocery stores.

And I ask the reader, whoever the reader is, especially if they're new to the cuisine, to also do that work. Because I had to do that work to learn how to make French pastries and pasta and spaghetti sauce. It's the least you can do if you're interested in the cuisine.

What are some of your favorite menu items in New York right now?

I have two very young kids, so going out to eat is less of an option for me. But we order in a lot: Red Hook Lobster Pound, this Malaysian restaurant called Langkawi. I love Doris [Ho-Kane]'s pandan coconut waffles. Her place is called Bạn Bè, and it's only open on the weekends.

Do you have a go-to bodega order?

Sausage, egg, and cheese on a plain toasted bagel.

What in your opinion is the most underrated ingredient right now and the most overrated?

Underrated: red palm oil. There's a lot of conversation about how it kills wildlife but I think they're conflating red palm oil with the palm kernel oil, which is used in cosmetics. Red palm oil has been made ethically for generations. There's a distinct floral taste and I love the wonderful orange hue it adds to dishes or your fingers. And then overrated… I don't eat a lot of cold salads or cold sandwiches. I like warm foods.

Is there a kitchen etiquette rule that you live by?

I've become very loosey-goofy with my kids now. When I used to run kitchens, I would [note] on a recipe I developed, “Do not veer from these standards.” I don't believe that anymore. I would say just pay attention to your senses. If you don't pay attention, that's when mistakes happen.

For more tips and opinionated takes from food experts, see our interviews with Molly Baz, Sohla El-Waylly, and Andy Baraghani.

in your life?

in your life?