Summer in the city is rife with parties, both cocktail and political (don’t forget to vote in the mayoral primary next month!). It’s a moment when tensions that remain submerged in other seasons rise to the surface. Who can afford to flee the claustrophobic streets? Who is working the outdoor tables, and who is loudly complaining that there aren’t enough of them?

This anxiety is, of course, welcome fodder for novelists. Party fiction is wealth porn as often as it is crime scene photography, devastating vivisections of the violent upkeep required to maintain that billowing tent out East.

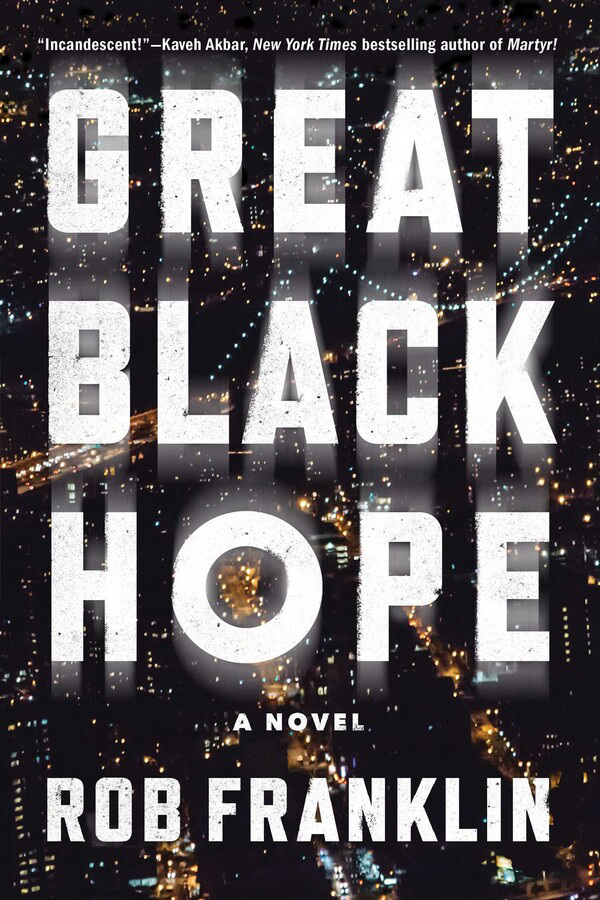

These stories feature summer nights rife with smog, hazardous highs, damp silk, and overfull smoking areas where, as Rob Franklin puts it in his hotly anticipated debut novel, “nightlife zoologists” gather. There is a long history of such social anthropology, ink-dipped and fabulized, in the canon of New York party literature. Edith Wharton’s Gilded Age carousers, Bret Easton Ellis’s deadpan and dead-inside stimulant fiends, Tama Janowitz’s drug-addled aspiring artists, and Ursula Parrott’s Prohibition-era, club-hobbing divorcees are just a few entries in this grand, sordid tradition, which also includes F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald’s liquor-drenched reflections on fast-sinking socialites and Nettie Jones’s sleekly wretched romp through ’70s New York, among a menagerie of titles I simply don’t have the word count for. This summer, Franklin’s Great Black Hope, out June 10, joins the pantheon.

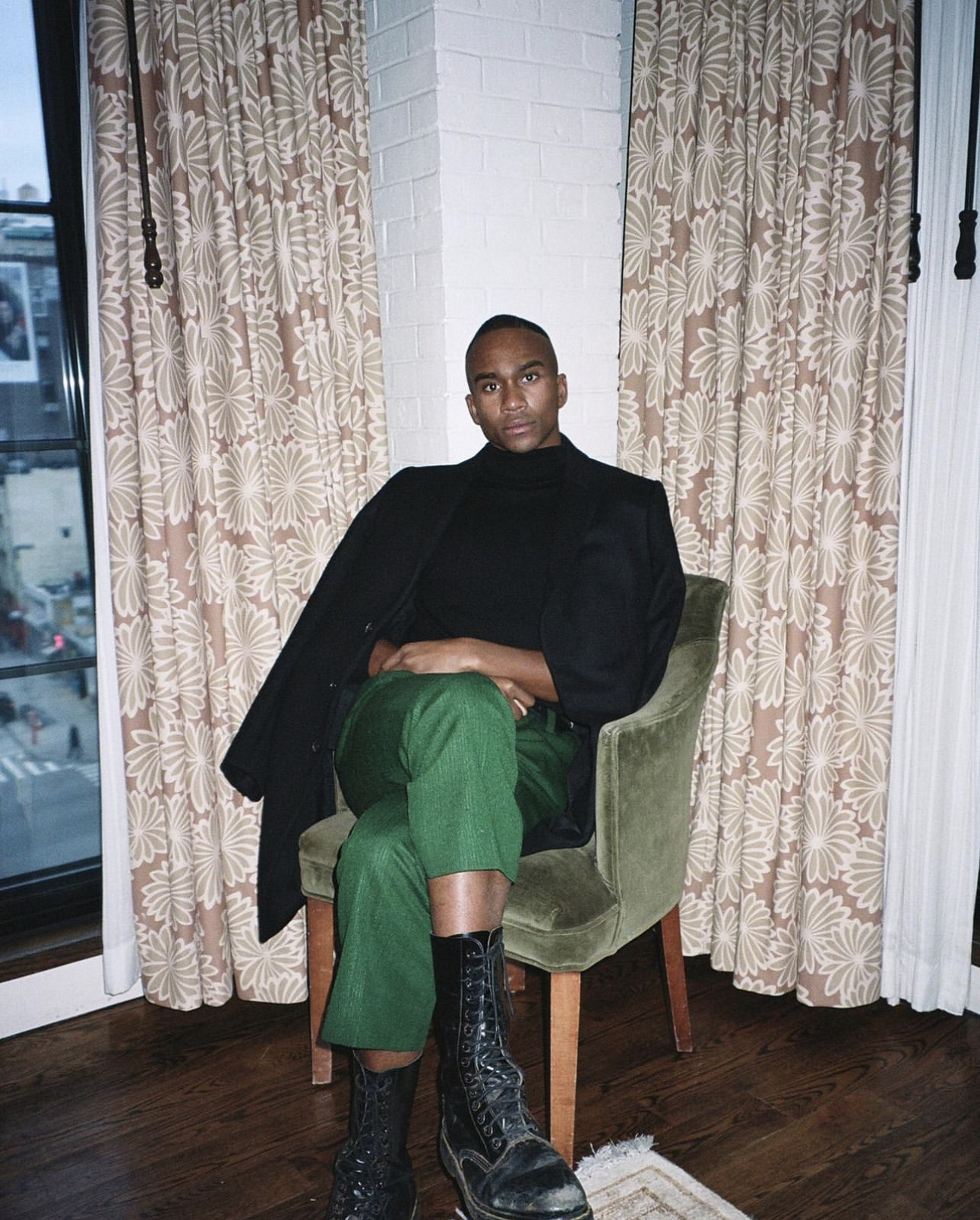

Franklin is a professor, poet, critic, and a co-founder of Art for Black Lives whose first novel follows Smith, a queer Black Stanford graduate, as he is thrust into intimate contact with the racism and classism of both New York’s criminal justice system and its media ecosystem. Mere weeks after the exploitative tabloid circus following the death of his best friend, the child of a renowned soul singer, on the night of her 25th birthday festivities, Smith is arrested for cocaine possession in the Hamptons, sending him on a spiraling journey through New York’s nightclubs, courtrooms, and basement recovery meetings.

Spryly satirical, intellectually incisive, yet still gracefully mournful, it is a series of beguilingly melancholic party reports, a lyrically rendered bildungsroman, and a wrenching elegy for a lost friend. With Smith’s story, Franklin slices into New York’s canon of party writing, only to find that boisterous nightclubs might also be mausoleums. I sat down with Franklin to talk parties, hierarchy, Gatsby, Kids, bright lights, and the big city.

We’re here to talk about a Venn diagram integral to New York literary history, which is summer in the city, parties, and parties occurring during summer in the city. Your book features a few, delivered with both shrewd satire and opalescent nostalgia. Of course, it is much more than a summer party book, but you must have read a lot of those as research, so I thought I’d start by asking you for some of your favorite books anywhere in that Venn diagram.

Absolutely. I mean, opalescent nostalgia, first of all.

Well, I have to compete with the blurbs, and they already used “incandescent.”

[Laughs] Well, you can’t have this conversation without mentioning Gatsby. Recently, I have been feeling like there’s a Great Gatsby bell curve wherein semi-literary people think it’s basic to name check Gatsby because we all had to read it in high school, but people who have written a novel recognize how rare it is for that perfect a novel to exist. There are so many mesmerizing sentences. Gatsby planted a seed in me at 14. So many of my favorite books satirize a social scene in a major city. I mean, The Bell Jar…

That’s a great one. Interns partying in New York honestly do not get enough literary play. Where is the Great American Phebe’s novel?

When I read the opening of The Bell Jar, which I re-read recently when I was waiting for Clandestino to open so I could get my laptop, which I left there the night prior—

There’s nothing I love more than ill-advisedly having my laptop out on the town, but it is really alarming when you forget it.

And I did. So I was sitting in Russ & Daughters reading The Bell Jar, thinking of Joan Didion living in New York after graduating. Something I love about the tone of both Didion and Plath’s sweltering New York summer party scenes is that they capture both a sense of possibility, a desire to consume every experience, as well as how alienated you often feel once you’re at the party. There are recent additions to the canon: I love My Year of Rest and Relaxation, The Guest, which both take a darker tone in looking at spaces of wealth, privilege, and indulgence. I also like a more earnest party girl book, something like Sex and Rage by Eve Babitz, which is heavily autobiographical lore of the It-girl in novel form.

You have a great line about becoming a “nightlife zoologist” while loitering in the smoking section. How did you approach rendering class analysis via party scene?

Nightlife in New York collapses so many different scenes and types of people who––in a different kind of city, say, London––often would not come into contact. So from a class perspective, from a race perspective, from an industry perspective, you’re getting a collision of people from different worlds forced into proximity. There’s often sexual or romantic tension there. There’s the opportunity for actual conflict. Parties are spaces where you’re seeing laid bare the mechanisms that uphold glamour. There is always a wizard pulling the lever that allows the champagne coupes to be passed around. The lights are a particular shade, the music’s a particular volume. Looking behind that curtain at the labor upholding that illusion is very interesting to me.

Your book features a few versions of the archetypal party girl, refracted through different race, class, and even passport prisms. The protagonist Smith’s party-girl friends—Carolyn, Elle, and Fernanda—remind me of an iconic line in Bright Lights, Big City, in which a girl is described as someone “you knew was the real thing when she steadfastly refused to acknowledge your presence. She possessed secrets—about islands, about horses, about French pronunciation—that you would never know.”

That’s really good. Many of the girls in this book know a lot of things about horses.

Tell me about writing your party girls—they have more interiority than many male writers would give them, while also functioning as vectors for your class and race analysis.

It’s astute to point out that those girls are an entry point for Smith into worlds unknown. Smith obviously comes from a privileged class background, but a very specific one culturally. Elle and Smith are both products of the Black bourgeoisie, but Smith is from a southern Black professional tradition—his parents’ friends are professors, doctors, and lawyers—and Elle is from a more moneyed, but less preoccupied with degrees and respectability, world in Los Angeles, which has its own rules. Smith is constantly asking: What are the overlaps between himself and Elle; Elle and his other close friend Carolyn, who comes from a wealthy, white, East Coast art-world family; himself and Carolyn? What does he know that they don’t know, and what do they know that he doesn’t know?

We love Venn diagrams here, so onto another one—party girls and party boys. There’s a tradition of party boy books by men like Martin Amis, Bret Easton Ellis, Jay McInerney, etc., about white guys that are often, if we’re going American Psycho, literally violent, or just very badly behaved, getting away with everything as they flit between parties. In this book, we have a party boy who’s committed a minor infraction dealing with the justice system, and grieving a friend who has died at the hands of a party. Were you aiming for an homage-meets-subversion genre?

So many of the party boy texts are about heedless consumption without consequence. That is very much a tradition with male writers and male characters, and Smith is not that kind of character. His passport to these rooms is revocable, and he’s perpetually aware of that. Smith understands that being wealthy and white has become unfashionable, at least without the veneer of multiculturalism, so he is aware of the cultural legitimacy he lends these people and what role he’s expected to play, and is meticulous about playing it. We see that when he steps out of line, as a Black gay man, there are ruinous consequences immediately.

Time moves very differently during the summer and at parties. It’s both more languid and more manic. I love the line when Smith wonders whether he has an addiction, and realizes instead he’s afflicted by “an unspecified malady, a desire for the night,” which feels like a craving for a type of time. Can you tell me about your approach on that front?

The sections that take place in summer in New York are more maximalist on a craft level—bodily sensory detail, how someone smells, how their breath feels when it hits your face as they’re talking to you closely at a party. On the sentence level, there’s more description packed in. Many things appear in a list, and many descriptions are juxtaposed to approximate the sensory overwhelm of summer in New York. When I think of great literature about summer in New York, I think of Goodbye to All That, Didion standing on a street corner eating a peach. It’s this moment of peace, indulgence: “No one in the world knows where I am right now. I’m not lonely, but I am totally alone.” I wanted to embed moments like that throughout the novel.

It’s a very different project to write a drunk protagonist, a high protagonist, and a sober one. What was writing those modes like?

The only scene in which we see Smith high is the opening one, which is formally unique. It is a more lyrical passage than we see in the rest of the novel.

Readers, it’s gorgeous. It’s giving prose poem. Actually, I wanted to tell you, it isn’t as staccato as one might expect for a coke scene—it was very dreamlike, a fugue state, yet anxiety still drips off the prose.

We’re in a moment where he’s just taken a bump and then the night becomes crystal clear again, but there is an anxiety. A scene that feels drunk and beautifully happy is the scene when Smith is on the bridge, coming into the city with Carolyn and Elle, and Carolyn is leaning her head out of the window of an Uber—

Two girls, one gay guy, tipsy in a cab?

Oldest story in the world.

Talk about a holy trinity, for once.

I know when I drink there is a tendency to sentimentalize things that could otherwise feel totally corny. If a sober person did that, you’d be a bit like, “Okay girl, let’s stick our head back inside.” Those things become impossibly beautiful in an altered state, but it is possible to embed that beauty into prose.

Let’s get meta, as in Meta, the company—the way you write about Instagram allows you to perform such subtle yet precise skewerings of your characters’ class positions, and class awareness, in that late 2010s era. Can you talk about fictionalizing social media?

It’s hard for me to picture writing something set in the modern day without including some degree of digital space. In Great Black Hope, we have headlines appearing on Google alerts and references to people’s Instagram presences. There are new frontiers of hyper-modern snobbery, there are references to how certain people are perceived in real life based on how they present online. Thinking of an author like Edith Wharton, I wanted to consider codes of conduct and update them: what are new ways in which people stratify themselves and create artificial schema of superiority?

On the Wharton note, writing a party is a specific type of skill—capturing the frisson of danger, the risk of humiliation, the high of the right joke—and you accomplish it deftly. Were there any party scenes in particular you returned to as inspiration?

One of my favorite pieces of writing is Jay McInerney’s 1994 New Yorker profile of Chloë Sevigny. McInerney is trying to pin her down so he can write the profile, and there’s a lot of attention paid to the fact that she’ll book a shoot and not show up, to the fact that the teamsters gave her a beeper so they can track her down when she’s needed on set. There’s a scene where they’re filming Kids at the nightclub Tunnel, and then we get a scene where Chloë takes McInerney to Tunnel. I must have read that before I sat down and wrote the [fictional club] Inducio opening scene because there are many things that feel directly informed by the structure of those sentences, and how he captures a bunch of kids doing coke in a bathroom.

The book starts with one party scene and ends with another: Smith’s memory of the last time he saw the friend he’s been grieving. There’s an indelible description of how “the room spun like a track along her center spindle.” Could you talk about the narrator’s changing conception of the New York party scene, and the way it refracts the city’s socio-political dynamics?

Something that unites those scenes is Smith watching someone he has a great deal of affection for across a room. It can make you fall in love with your friends again to see the way they can delight a stranger. Smith is a character with a tendency to turn towards cynicism. Those are moments when, despite the nearness of tragedy, there’s so much humanity. I definitely wanted that sense of wary hope to end the book.

I think that’s a beautiful note to end the semi-serious portion of my questions with, so—what is a party from history you’d attend if you could?

When I was naming the character Fernanda, I came across an old news item from the early 20th century about a debutante named Fernanda Wanamaker Wetherill. She’s an iconic spiritual predecessor for the book.

Oh, you know I love a dead heiress.

Of course. So our dead heiress had her debutante ball at her family’s estate in the Hamptons, but they also rented a neighboring estate for the after-party, and they totally trashed the place. They were doing target practice with fine china. Someone was swinging off a chandelier and it collapsed. They all got arrested and put on trial, and it became a nationwide story about the godless indulgence of the wealthy. I would have loved to see it.

Can you name something underrated, overrated, and accurately rated?

Underrated is Romy Mars, Sofia Coppola’s pop star daughter. I think she’s earnestly a very good pop star. She’s combining the themes of Sofia Coppola’s movies with the French electronic music production of her father, the lead singer of Phoenix.

And this is why sometimes a nepo baby is actually just an iconic collab…

Yes. Okay, overrated… I think that the concept of having to get a Real ID is deeply overrated and kooky. It’s just like, I already have an ID. If you’re going to have a thing called Real ID, why even issue a not-Real ID? Accurately rated is going for a walk during this one month of reasonable weather and listening to a song, an audiobook, a podcast, and maybe having a little coffee, calling a friend.

What is your favorite place in New York to people watch?

Cipriani in Grand Central Station. I have a quarterly celebratory daytime martini with a friend there, and we overlook the whole room.

Favorite place in the city to get in an argument?

That’s going to be a park. It’s not Central or Prospect because those are places where I like to run, that I consider really meditative. Tompkins, McCarren, even Madison Square, the smaller parks—that’s a lovely place to get in a little tiff.

How about for flirting?

I used to call the bar at the Rosemont “the boyfriend store,” because every time I went there I would meet someone I dated for at least a couple months. But now I’m getting too old to patronize the boyfriend store because the inventory on offer is giving 22 to 26. It’s not really a place for a man in his 30s.

It’s not really a place for a man on the cusp of international literary fame.

[Laughs] It’s not appropriate. So my new favorite place to flirt is my Instagram DMs. Get in touch.

in your life?

in your life?