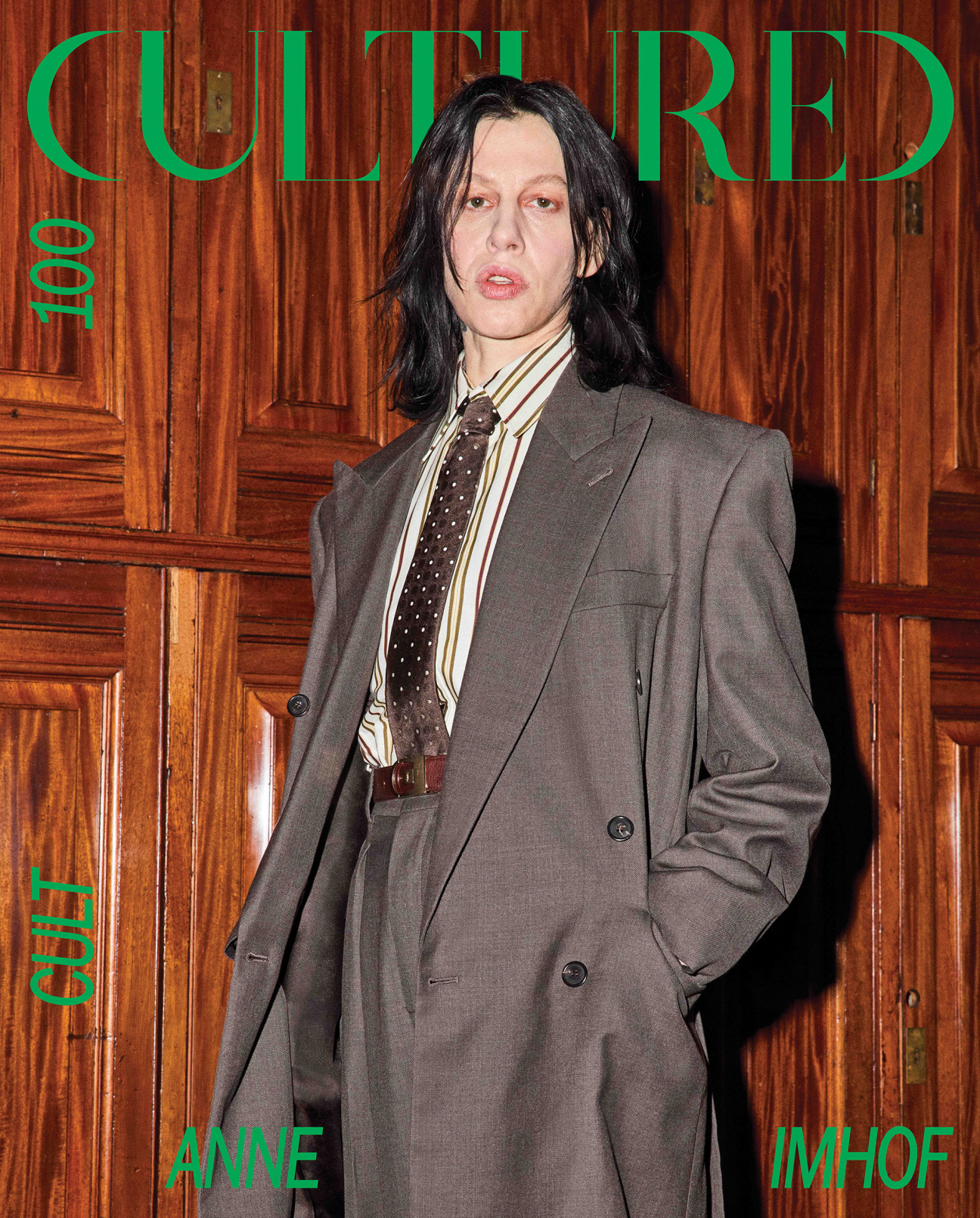

CULTURED’s second annual CULT100 issue spotlights 100 names across five generations who are shaping our culture in real time. Some members of the list are household names; others have been working behind the scenes to make possible the encounters that stop us in our tracks. They are all thinking big, sharing generously, and embodying courage. We hope their work makes you a little braver, too. Order your copy of the CULT100 issue here.

DOOM, the title of Anne Imhof’s three-hour performance which premiered at the Park Avenue Armory this spring, spelled backward is—well, you can read it for yourself. That seemed to be the haters’ main complaint: The sprawling piece—part tableau vivant, part promenade theater—was all vibes.

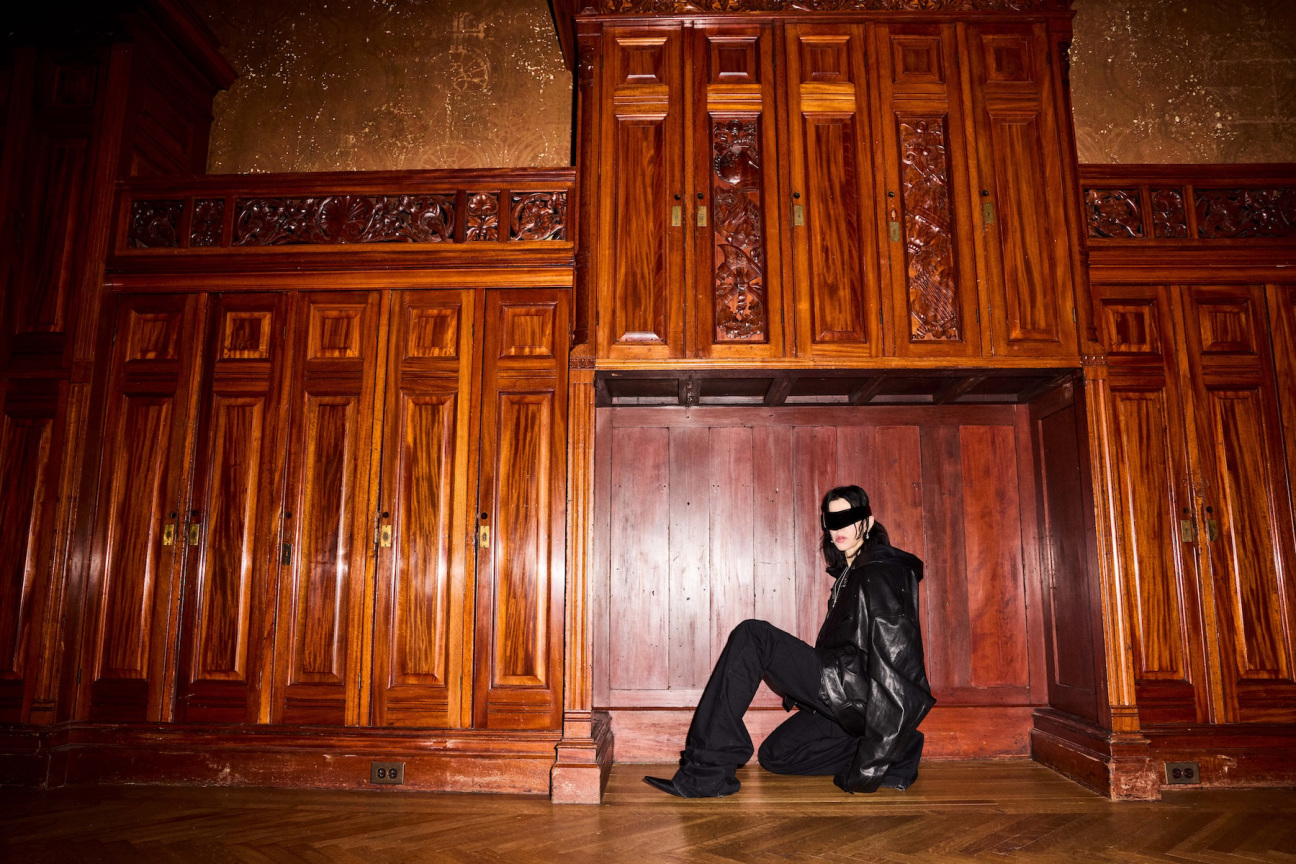

I wonder, though, did those who so quickly dismiss the piece really try? On opening night, I entered the 55,500-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall a skeptic and left a believer, won over in part because of the demands the work made upon me—to maneuver through and against the crowd for a vantage, to acclimate to the night’s shifting temporality, and to attune myself to the surprising emotional range of its detached melancholy and menace (yes, its mood).

The artist, who splits her time between Berlin and Los Angeles these days, is not yet halfway through the show’s nearly two-week run when we meet to talk in one of the upstairs rooms at the Armory. The fabled military facility and Gilded Age social club—emblematic of American industrialist wealth—was a fitting site for Imhof’s revised lexicon of oligarchic force.

Downstairs, steel barricades, a Jumbotron countdown clock, and 26 black Cadillac Escalades formed the ominous mise-en-scène for the show. Later, spotlights would lead the audience around the dark, hangar-like space, through the dispersed cavalcade of empty cars. Perhaps hitting upon a new slogan (Cadillac is a sponsor), she adds, “It’s full of power and beauty—for the people who are safe inside it.”

Imhof traces her sense of dystopian threat back to childhood. Born in 1978, she grew up in the German town of Giessen, located in the Fulda Gap—a lowland corridor identified as a likely path for Soviet tanks should the Cold War turn hot. That ambient tension, and the more explicit fear that “Chernobyl could happen again,” provoked a deep depression at age 11, she recalls. In Frankfurt, where she moved to as a young adult, she discovered punk (“It was the anger that resonated with me”).

“I wouldn’t say I’m an activist; it doesn’t make me an activist to have some notion of what we do as a group.” —Anne Imhof

By age 20, she had a baby. “I was like a panther in a cage at that time,” she says, “and I was also, in a weird way, a very happy mom.” Such apparent contradictions seem to have served her well, at least creatively. She graduated from the storied Städelschule art school at 34, and eventually, became an internationally acclaimed artist.

It was Imhof’s Golden Lion-winning performance, Faust, made for the German Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, that announced her arrival. Her beyond-buzzy, one-to-watch status has never flagged since. Neither have her fundamental artistic concerns changed. Looking back at that breakout endeavor—whose desultory, S&M-inflected ensemble action was likewise imminently Instagram-mable, fragmented, and impossible to view in its entirety—Imhof compares the hierarchy evoked by the architectural intervention of its fishbowl set to that established by the Escalades.

“I was working a little bit in the same way—I was thinking about the transparent glass panes that I saw so much, in luxury stores and banks,” she recalls. “You pretend that everything is transparent and equal because you can see through it,” but, referring to the raised floor in Faust, through which viewers could observe a crawl-space-like stage, she notes, “When you take a glass and [lay it] horizontal, suddenly you know [that all is] not equal; there’s an above and a below.”

Visibility, voyeurism, and surveillance are implicit themes in all of Imhof’s work, but so are intimacy and community, despite its often studiously blank affect. The artist leverages a distinctly alienated glamour, anchored in the physical beauty of her fashion world performers—perhaps especially in the brooding charisma of artist and model Eliza Douglas, her longtime collaborator and former partner.

This adjacency is seen by some as working counter to an image of authentic collectivity. But the stunning political hostility of our moment throws another aspect of Imhof’s world—what is queer, trans, nonbinary, feminist, collaborative, non-hierarchical, countercultural, disaffected, like-a-panther-in-a-cage about it—into sharp relief. Coolness is matched by sincerity.

Alternatively, these two elements clash—producing a palpable awkwardness, like in DOOM, where the piece’s aloofness serves as an unlucky foil to its unironically overplayed existential and romantic tropes. But I’ve always preferred work that errs on the side of corniness, as topical forays into “the political” often do.

“The people who perform, they know what they can hold and what they can’t. That’s what I trust in.” —Anne Imhof

When I ask about Imhof’s response to the repressive climate in the U.S., she replies, “I wouldn’t say I’m an activist; it doesn’t make me an activist to have some notion of what we do as a group.” It was Douglas’s idea, she says, to make the cardboard protest signs that appear at one point during the night. (“Save the Dolls,” “You Can’t Control My Body,” and “Trans Rights” were among the slogans.) Imhof seems to see this content—whether explicitly articulated or not—as a given: “The people I work with are vulnerable.”

The cast of nearly 60 performers included actors, dancers (from the Flexn scene and ballet), models, musicians (a pianist and a punk band), skaters, and other category-defying participants. Douglas watched, waited, vaped, and sang as the evening’s sequence of vignettes unfolded.

With the characters (sometimes) dressed in the sports jerseys of fictional, dueling high school teams, Imhof taunted us with the plot structure of a feud. But her hybrid script, drawing from such far-flung sources as dance criticism and Rimbaud, hung its action on a skeletal, backward version of Romeo and Juliet. DOOM asks, What happens when you play a tragedy in reverse?

Imhof tells me that the idea for the star-crossed lovers’ death monologues to occur at the beginning originated with the actors. Ultimately, actor Talia Ryder (the show’s primary Juliet) insisted on the flipped structure. Imhof hesitated but gave in: “It was a good choice,” she says. “The people who perform, they know what they can hold and what they can’t. That’s what I trust in.”

From the interpretation of archetypal roles by ballerina Devon Teuscher to music director Ville Haimala’s sweeping electronic score or Klaus Biesenbach's curatorial eye, the artist brings our far-ranging conversation back, again and again, to the inspired contributions of those around her. The severity of her aesthetic is complemented by her in-person warmth—or fervor, even.

Perhaps, ultimately, it’s that fervor that makes her art such a topic of critical (and group chat) debate. It’s epic, ambitious, and forbidding, but also unpolished: rendered charming by its sincerity, ragged edges, and even its hiccups of teenage cliché. To see an artist court disaster on such a grand scale is arguably a mood, I suppose, but I think Imhof—with DOOM, and in her general practice—gives us more than that to sit with. As the artist turns toward a more structured, scripted, tightly choreographed approach, vibes become an asterisk.

THE CULT100 QUESTIONNAIRE

When you were little, what were you known for?

I was the Dreamer.

What’s something people get wrong about you?

The introvert/extrovert thing. I’m an introvert.

What question do you ask yourself the most while you’re making work?

Is it good?

Who do you call the most?

My daughter.

What’s one book, work of art, or film that got you through an important moment in your life?

I listened to Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” just before I gave birth to my kid; also “Foxy Lady.” And then a very influential book would be Rimbaud's A Season in Hell.

What do you think is your biggest contribution to culture?

Not to have tried to make art. Not to have tried to make, like, “real art.”

Hair by Cody Ainey

Makeup by Ernest Robinson

Production by Dionne Cochrane

Tailoring by Chloë Boxer

Styling Assistance by Keanu Mohammed and Dylan Keoni

Production Assistance by Brittany Thompson and Kaylah Dawkins

Location: Park Avenue Armory

in your life?

in your life?