I believe the first time I saw Torey Thornton’s work was in 2015 in a group exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Since then, we have interacted with one another in a spectrum of group settings: a baseball game, a holiday party, various openings, a wedding, a bachelor party. We’ve also had a number of daytime meals out with one another. We text and email. I’ve never been to his studio, though I have seen exhibitions of his work.

I know that for others who occupy similar positions as mine (not the artists, but the writers, dealers, curators, researchers of the world) it can be irksome to meet with an artist over breakfast instead of their studio. However, I’ve come to think of the studio as a site like any other. If we understand studio practices and the practices of exhibitions as architectural projects—rooms through which people navigate, these navigations effected by objects—then for me, right now, being seated at table in a restaurant is just as good a setting as any to talk. In other words, the here-and-now can occur in any place—the future as a site of hope and apprehension and the past as a site of memory are narrative projects, anyway.

So, of course I was pleased to be asked by Thornton to talk with him in advance of his January 2019 exhibition at Essex Street gallery. I think that in the exchange below we set a good foundation for the forthcoming exhibition: by exchange I mean that of the interpersonal, but also a laying out of how disparate parts operate with and alongside one another—how objects might correspond with one another in, say, a solo exhibition.

Thornton is represented in major public collections, and earlier this fall his work was included in “The Vitalist Economy of Painting” curated by Isabelle Graw at Galerie Neu in Berlin. Thornton’s painting was hung between works by Ellen Cantor and Albert Oehlen. What draws me to Thornton and his work is common between himself, Cantor and Oehlen: an unapologetic and disruptive opposition to the status quo, and a practice that explores the extremities of narration and abstraction. In the conversation below we touch upon these themes and spend some time opening up the field in which his coming exhibition will be situated.

Andrew Blackley: I recently spent some time uptown looking at exhibitions and two bodies of work struck me. The first was Jack Whitten’s “Black Monolith” paintings which are composed of tesserae that he made by curing pigmented acrylic in refuse (bottle caps, plastic packaging) repurposed as molds. Once cured, he would cut, break or otherwise shape each tessera as he saw fit before arranging them together as and on the painting. The other body of work I saw was a group of six or seven collages by Jean Dubuffet made in the 1950s— each work features dozens of butterfly wings which serve as the primary compositional material of the works. These two bodies of work were similar in that they were physical arrangements of what appear to be common materials, but as much as they shared some ethos of combination, collage and accumulation, the materials they used were nearly opposite from each other: Whitten’s materials were plastic, static, constant, while Dubuffet’s were fragile, particular and iridescent—and already existing with a design and decoration in and of themselves. One material was fully formed, and the other—Whitten’s— well, he formed the material fully.

What do you see as your building blocks—or, to use different language, your alphabet, your foundation, your arch stones? I am recalling the two works that you showed at the Whitney last year—Painting and What Is Sexuality, Is The Scale Infinite Similar To A Line (both 2017)—there’s a lot to talk about with those works and their materials.

Torey Thornton: For each piece I approach it differently in terms of material focus, and of course there are different approaches for the paintings versus the sculptures but, in either case, I’m always considering what the content and form of the piece should be and then that dictates materially how I choose to compete with the medium that I’m working in, sculpture or painting etc., or how to highlight the realm. There are works that attempt to undo the stereotypes surrounding the medium and there are those which heighten the medium, or have other agendas outside of the medium itself. The content may focus on subjects that are more worldly or not as rooted in an art criticism discourse or direct analysis of the space in which the piece is made. These two works you mention are both paintings, and in many ways they are both about pushing the definition of painting and lifting up the definition to look behind it. In the case of Painting, I considered the round saw blade as a surface just like a paper, panel or canvas, and I wanted to work with materials that softened or competed with the steel so I chose to work with the found painted rocks, seeing them as similar to collage. With the mattress I used to make What Is Sexuality, Is The Scale Infinite Similar To A Line, it’s more complicated in terms of discussing its origins and various meanings, but materially I knew that having a surface that was a canvas would inevitably talk about painting along with the actual painting that I applied to its surface. The additional binding materials and plastic forms on top were about boosting the concepts in my mind but also still seeing the materials as applied collage. A shallow hard painting and a thick soft one, in many ways. I have rules, though. None of the sculptures use paint by me, or at all really, and all the paintings have paint involved. This is just a way for me to allow my brain to settle and navigate the work, otherwise things get too open-ended and free in ways that don’t suit my work.

AB: We still talk about painting and sculpture as if they’re totally distinct, like two parallel lines and lineages that never touch. Maybe it would be more useful for us to think about painting and sculpture as intersecting and overlapping, like x and y axes. What’s going on in the studio and in your head when you’re working towards a new exhibition? Besides what is going on in the studio, what does it mean for you to sequence works and to sequence exhibitions? I have a feeling that you take the time between each occurrence, be it a work or an exhibition, as important—that’s what creates intervals, rhythm, cadence, etc.

TT: There’s a certain pacing and trajectory that I have attempted to develop and follow inside my mind. How do I create the most space for myself to work in freely while still keeping strong pressure on the concerns I have within art-making? Generally, once I’m showing work, I’ve already thought about the work and shows that will need to follow in order to create the right context and conversation for the things shown, before and after, that existing show or piece. I don’t really work serially in the same way that many artists do, so sometimes it makes it difficult to determine which works should go where and why, but this also keeps me stimulated.

I like to have something to push against. I guess the works are like words and the shows sentences, so the overall practice is a statement or a paragraph. It takes years to have the statements speak clearly but most people would rather fast-forward or tell you what your statements are versus waiting for you to finish speaking. I’ve realized that instead of moving in a straight line I move more up and down, sideways and backwards in order to pull in the necessary information to support whatever I’m working on at the time. My practice isn’t one long narrative, it’s more related to several streams of thought overlapping and interacting at once, how the brain generally works. I think the main focus is to not move too far ahead of myself when making work for a show and to make sure that I’m thinking things through and putting enough glue in the cracks if you will, versus hopping over statements (works) and moving onto the ideas that speak the loudest to me. Sometimes I have to slow down and really dig inside of a space and struggle or play within it, to get to the other side. I like to think that also in every step forward I dip backwards some and borrow from my past, but I never want to stifle myself or feel imprisoned, so I have to do what the work tells me to versus imagining what the viewer or world is ready for and/or thinks makes sense for me and my work. There are definitely particular pieces and shows that I save for the right time or moment. Sometimes there’s a show in my mind that’s three shows away from the current one because I need to present a body of work or ideas before certain work can be digested more comfortably.

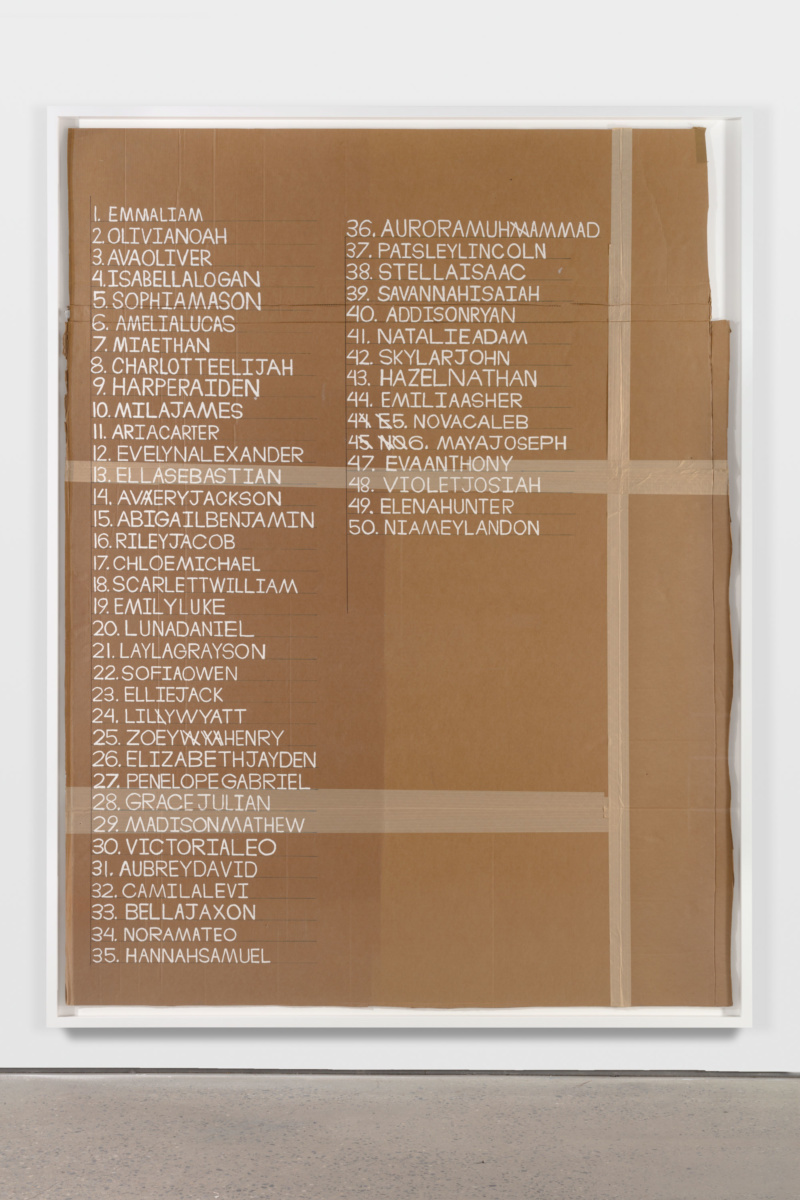

Abrasive bombardment can be nice and important at times, but I want people to be able to read and look without causing unnecessary confusion or shock: There’s a time and place for everything. This show at Essex Street in January will in many ways be the most proper presentation of my sculpture to date. It will definitely be a particular introduction to my vocabulary and material sensibility within sculpture, and there are also some overarching concepts that will be present, without speaking too explicitly about the show, too soon.

AB: I’m drawn to what you’re saying about the word/sentence/paragraph structure. In as much as these are containers of accumulation, they’re also active devices of structure: paragraphs organize sentences, sentences organize words. (The poet Ron Silliman writes, “The paragraph organizes the sentences; The paragraph is a unit of quantity, not logic or argument; Sentence length is a unit of measure.”) These forms can also serve as the site for disorganization. Will you talk about the titles of your works? They’re within the grasp of recognition but they are also elusive and are off-kilter, out-of-sync. They differ and they defer, for example: I against I, Surgically Removed Organs Left In I Against I, Creative Asphyxia, Intellectual Asphyxia, Romantic Asphyxia Painting and Am Not, You Want, (Analog Digi) (both 2017). It seems that you’re utilizing the moment where narrative shifts in scale or direction as the production site for meaning. If that’s true, or could be true, I think it could say a lot about how one might successfully navigate your exhibitions, which I suppose are also not serial, but simultaneously emerge from precedent and disabuse us of a loyalty to linear sequence.

TT: I used to have a difficult time determining titles because I wasn’t interested in flat fake poetic ethereal titles that could just be attached to anything that exists, and I wasn’t interested in blank giveaways, like “Large Brown Pit” in reference to a work of a hole dug into the earth. I always want my titles to be a work in themselves but to also give indicators or clues to the way my mind works in relation to constructing each piece, or otherwise. When the titles are read, eventually I hope people recognize shifts in my voice and attitude. I believe that a type of mystery is generally more interesting in artworks. Titling in some ways has become harder for me as the work has grown more conceptually rigorous and complicated.

I would like viewers to take their time with each work and exhibition by comparing and contrasting language, form and image, sequence. All of these characteristics influence speed, which also relates to something I call “the work’s rewatch value.” Similar to a movie, each work has a certain number of times it can be seen before it is empty or uninteresting. When thinking of certain artists, I often obsessively dig and try to find common threads or quiet reveals in the work or exhibitions. This could be repetition through language or reference to other works in the past, formally, conceptually or linguistically. I hope that someone would take the time to investigate these threads and clues in my work, as well. Societal systems and technological advancement have halted a type of mental porousness or digestion of information. Things slide through and over our heads much faster, and in some ways I feel that this helps move me to loop back and reference works from my past and evolve or anchor their language or progression through a different context.

AB: Are you suggesting that the “rewatch value” of a work is a value that depletes through experience? I’m interested in agreeing with you, not because I think that works and their meaning and value are not accumulative, but I do think that some works become entirely recognizable. I’m interested, and I think you are too, in the unrecognizable, or something that teeters on the brink of recognition. That’s what makes reference and reception so rewarding: both tools rely on difference and the “new,” thereby prompting the viewer, and I suppose the maker, to construct new frames and boundaries. Speaking of boundaries and frames, how might one lay out a sculpture exhibition? Would the relation of the pieces to the whole resemble more a celestial constellation or an archipelago?

TT: I think some work just isn’t as interested in holding the viewer for longer periods of time. Maybe it just wants you to say “wow” and understand it relatively quickly. In other situations, work is possibly too simple or doesn’t leave much room for question, or no room to come back to it at another time and realize new dimensions that it possesses. Inevitably though, as with anything, the more you see something the more desensitized you become to that thing or situation. If you watch The Skin I Live In (2011) by Pedro Almodóvar as many times as I have, you will be less surprised and maybe won’t feel sick or angry towards the end of the movie.

All exhibitions are different for me. Aside from the materials or mediums shifting, there are always subjects or concepts that I’m playing with, building on or pushing against that dictate the work that I make for each show. For some years I felt that I was making painting shows predominantly as an introduction of my hand, vocabulary and environment to the viewer: this is what my paintings can look like and how my mind works. Now that I’ve begun to present more sculpture in full, in some ways the current shows will inevitably be a new introduction within this space of working. What is sculpture and what is material. How do I see sculpture materials and the meaning surrounding them? What are my forms or concerns and interest and so on? Although, for the Essex Street show, there will be some common threads between the works, beyond my hand of course, creating an ecosystem of sorts.