“Sometimes consuming food is a pedestrian act, but sometimes it’s a social and political one,” says curator Anonda Bell, whose exhibition “Feast & Famine” at the Paul Robeson Galleries in Newark brings together work by 56 artists including including John Baldessari, Robert Rauschenberg, Renee Cox, Mary Mattingly and Wayne Thiebaud. We spoke with Bell about the layered implications of what and how we eat—and the ways that art can shape our experience of food.

“Feast and Famine” is a vast exploration of food and its social, political, and bodily components. It includes works from 56 artists spanning a diverse range of media. Can you talk a little bit about the range the show covers and what you want the audience to take from that?

BELL: When I started putting the show together with my colleagues, we knew didn’t want to do an exhibition that was lots of still-lifes of beautiful foods. In keeping with the mission of Paul Robeson Galleries, which is about activism, we wanted people to come away from the exhibition with a sense of questioning things that they may take for granted in their life, which is what they put into their body everyday. We’re trying to draw attention to the fact that any kind of consumption is in some way a social and political action.

On tours of the exhibition, I offer people dried, roasted crickets. This has been an excellent way to start the conversation because people are either intrigued or repulsed by the idea, when in actuality, they’re both a historic, nutritious food and a future food. We also talk about other future foods such as algae, sea greens, plants that are grown in water, and 3D food printing. I want people to start thinking about where food comes from, why we’re putting these specific foods in our bodies and our attachment to food.

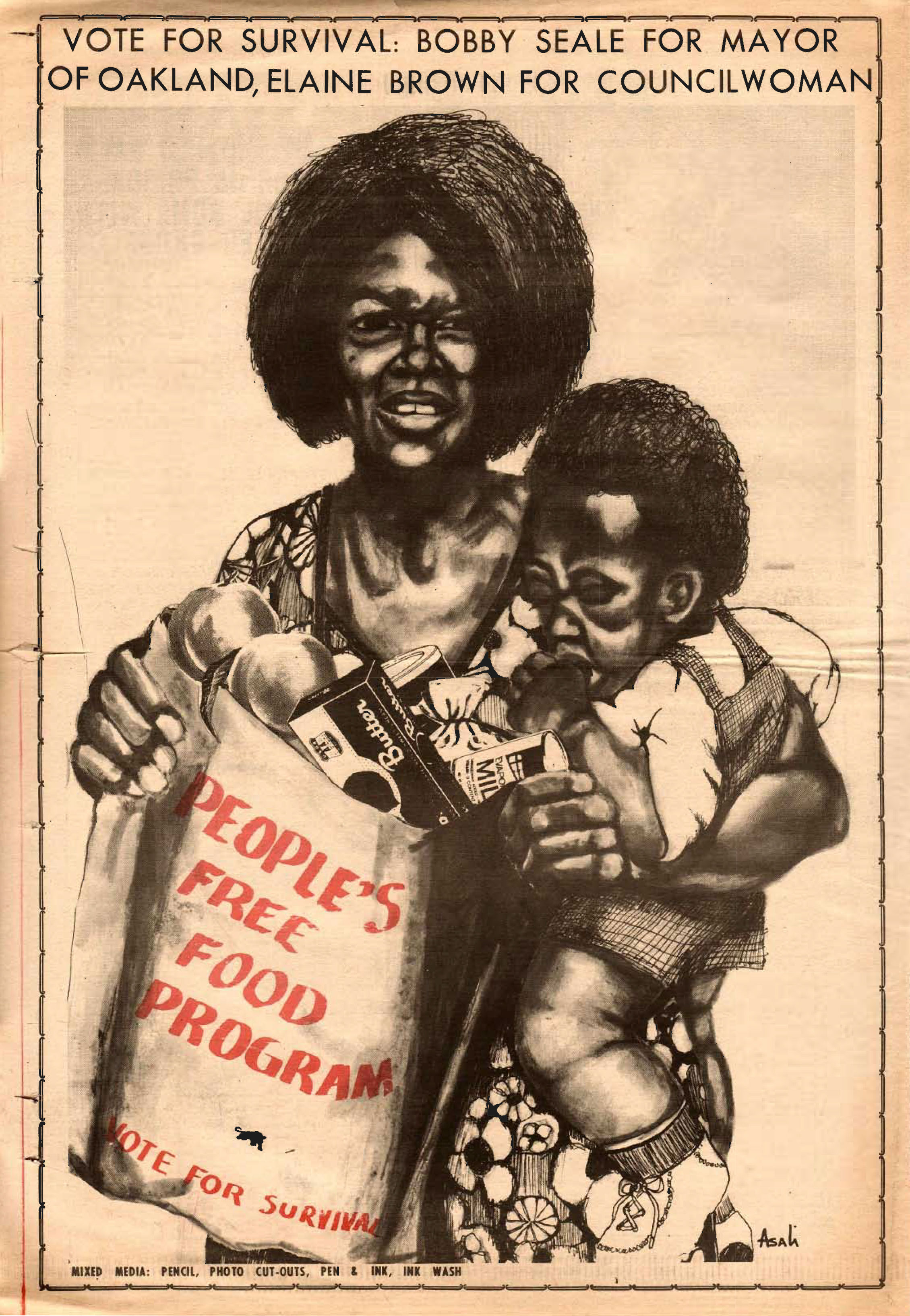

The show has contemporary pieces, such as recipe cards from Conflict Kitchen, a Pittsburgh restaurant that sources its ingredients from countries the U.S. is in conflict with, as well as more historical ones, like Emory Douglas’s Black Panther posters promoting community breakfasts. How have the conversations around food changed over the decades?

BELL: We wanted to break down the hierarchy of fine arts, so one of the starting points of the exhibition was looking at the Black Panther movement in the early 1970s, where they were trying to get breakfasts for kids provided in school. The projects they were doing were really amazing and very ahead of their times. There was an understanding that if kids went to school without breakfast, their ability to function for the rest of the day was going to be diminished. It’s nearly 2020, and now the issue is the quality of the food that’s provided because it can consist of things that have a lot of sugar or fat, which is not healthy.

Conflict Kitchen is using food to facilitate an understanding of other cultures through offering food that you might not otherwise have access to. People in New York City take it for granted that we can find food from many countries of the world, but that’s not necessarily the case for the rest of the country. The food at Conflict Kitchen is wrapped in packaging with information about the food’s country of origin. It’s educating people, but in a way that’s not explicitly didactic.

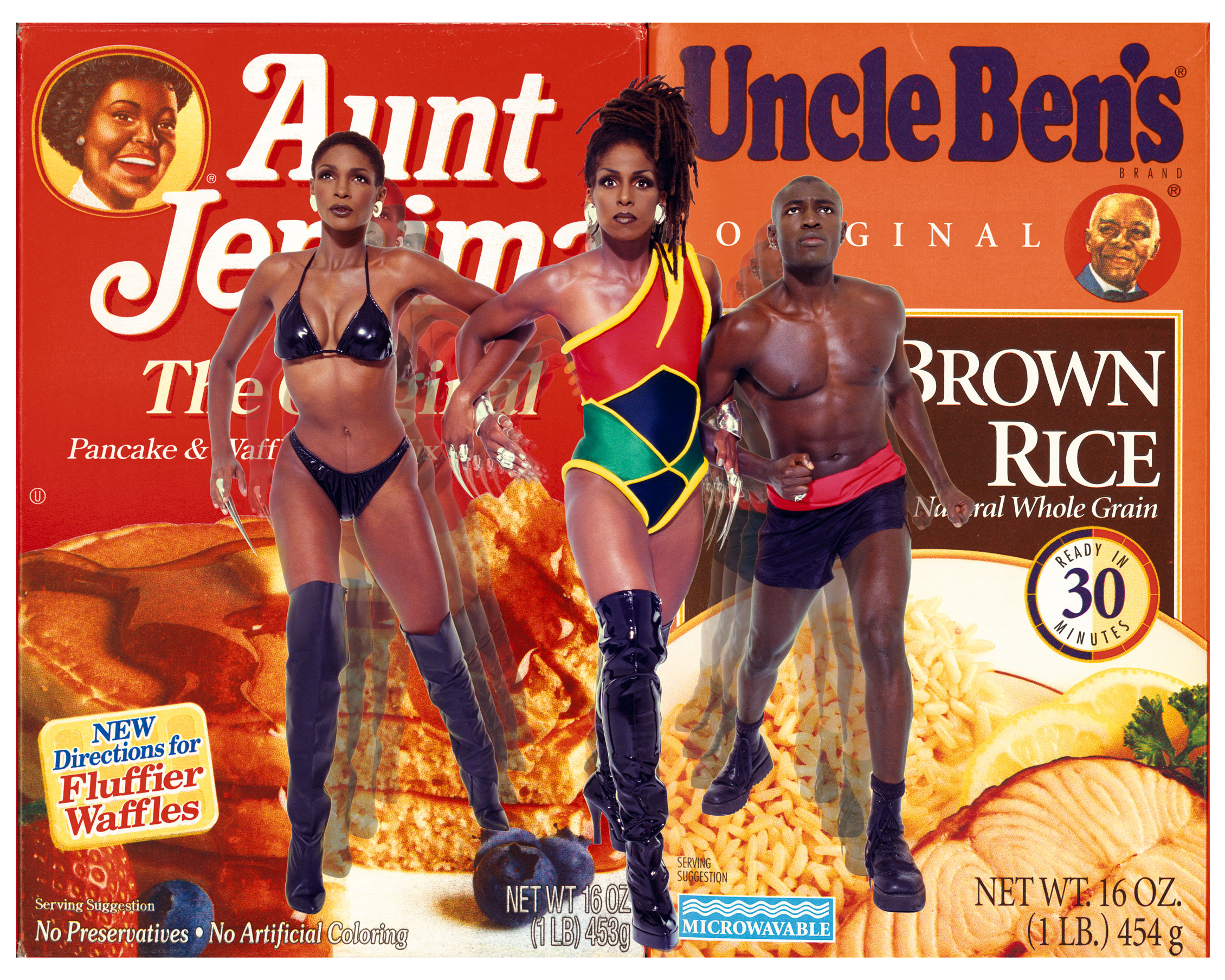

The exhibition explores a multitude of issues—morally coded brands, the role of food in global economics as well as its environmental impacts. What do you think makes the topic of food in art so all-encompassing?

BELL: Representing food within art is not a new thing. Cave paintings showed buffalos being hunted for food, it’s an enduring topic. It’s something that everybody does everyday, but we don’t actually think about it all that much. The exhibition asks people to think about where their food comes from. Did it come from a plant? Was that plant grown locally? Did it come from the other side of the planet? What are the costs of that food—not just transporting it, but the carbon cost, packaging, what type of plastic is it wrapped in and what does that plastic do to the environment? All of these things are touched on in the show. Hopefully when people leave the exhibition, they aren’t thinking of food as “good” or “bad,” but instead they are thinking about all the aspects of food that they’re putting in their body and why they’re doing it.

Can you describe what it’s like to walk through the exhibition?

BELL: The way that we’ve made up the show is a journey which starts with looking at water, talking about the starting point of food. In Newark, we have a water crisis that is not dissimilar to Flint in terms of aging infrastructure and unacceptable levels of certain chemicals. It’s a problem that’s going to need to be addressed, and it’s not going to be an easy thing to fix. We start with that, and then we go through food production and we have part of the show set up as a supermarket isle, and then we look at the psychological aspects of food, and then we finish with a wall of posters. They start with the Black Panther ones, but they go through a number of artists who are using food and raise questions around it. Do you use food stamps? Are you buying it yourself? Can you afford organic food? What are the implications of water access and the Dakota pipeline? There’s a whole plethora of contemporary art posters that then give you a whole lot of issues about food once you think about production and psychology.

Why do this show now? Is there a particular relevance to this moment?

BELL: I think that part of the inspiration started from the fact that Paul Robeson Galleries are now 40 years old and we’ve been in the city of Newark for 40 years. When I arrived on campus, access to a supermarket in the downtown part of Newark was impossible. People would commute to Manhattan to buy food. In the last two years, the gallery has moved into a new building which is part of a project called Express Newark, and within this building there’s a Whole Foods. Whole Foods, in some circles, is seen as a preemptive indicator of gentrification. If somebody told me that I would be in an office upstairs, and downstairs there would be a Whole Foods, I would’ve laughed. Prior to this, we were quite literally in a food desert. So I was thinking about food in a very specific nutritional sense and thinking about access to food in terms of food deserts and Whole Foods, and what that means in terms of signifying a change in the community. I liked the idea of choosing something that hopefully seems straightforward, like food, but is actually incredibly complex.