It is unfortunately commonplace that cultural commentary written decades and centuries ago feels increasingly relevant today. While many are familiar with the works of Jean Genet and William Faulkner, the name Jack Black carries with it a different connotation. This is not the Jack Black of early 2000s comedy and Tenacious D. This is the St. Louis born drifter, grifter, opium addict who made a career of burglary and prison stints. Black is the author of You Can't Win, an astute critique of the American penal system and fallacy of the American Dream. Long-time NY Times writer and novelist Randy Kennedy, who now oversees special projects at Hauser & Wirth, has teamed up with the Fortnight Institute to curate an exhibition "lying within the penumbra of a book." Alongside Fabiola Alondra, the founder of Fortnight and art book publisher, the two have created "You Can't Win: Jack Black's America" on view now through August 18. I checked in with Kennedy to discuss the show and Black's contribution to the modernist anti-authoritarian tradition.

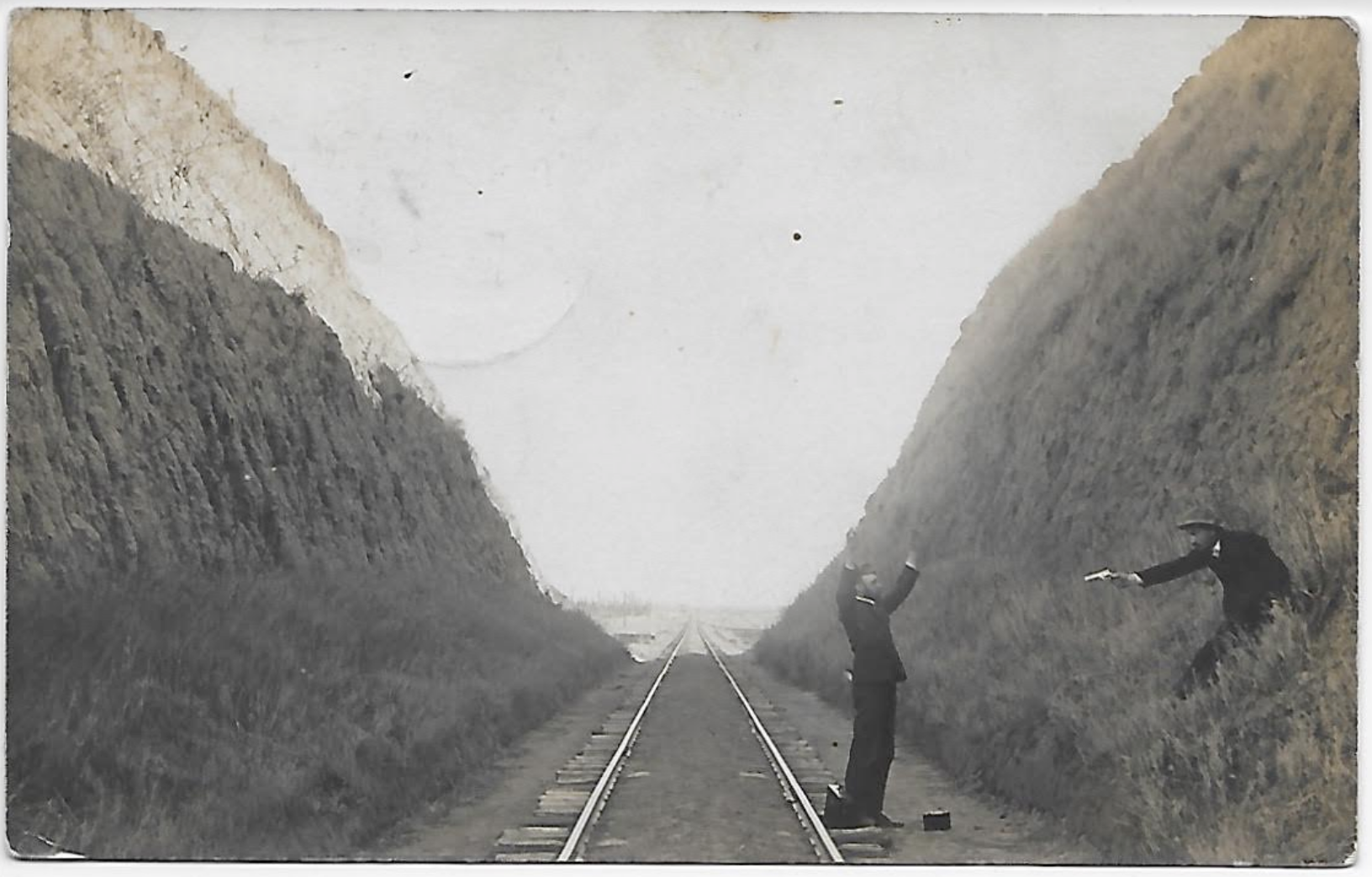

When did you come to You Can’t Win? Did you grow up knowing about Jack Black? Can you talk about Presidio in relation to it? I went through a big Burroughs phase in my twenties. Somewhere along the way in reading him and reading about him, I came across mention that his world had been upended by reading a book called You Can't Win during his disaffected youth in upper-middle-class St. Louis. I found a paperback copy and loved it. When I started collecting first-edition books, I quickly discovered how hard it was to find and so it became a kind of holy grail for a while, along with anything else by Black.

What were the characteristics of the work you were looking for in the curation process? Were they aesthetic or artist based? Aura? Subliminally charged? Fabiola and I have been in a long conversation about books and art for a few years now, and when she proposed the idea of me organizing a show for the gallery, the first thing that came to my mind was a show inspired by a book. I wrote a piece about You Can't Win a couple of years ago for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's wonderful Open Space publication and so it was fresh in my mind again. I proposed using it as the ur-text for a show and then started thinking about artists whose work chimed with the feel of the book. I put together a wish list and it evolved slowly. Fabiola also brought a few artists into the conversation and then we went out asking galleries and collectors. Even though most of the artists in the show are not "outsider" in any traditional sense, I think the show ended up having that feel, which is wholly appropriate under the guiding spirit of a constitutional outsider like Black.

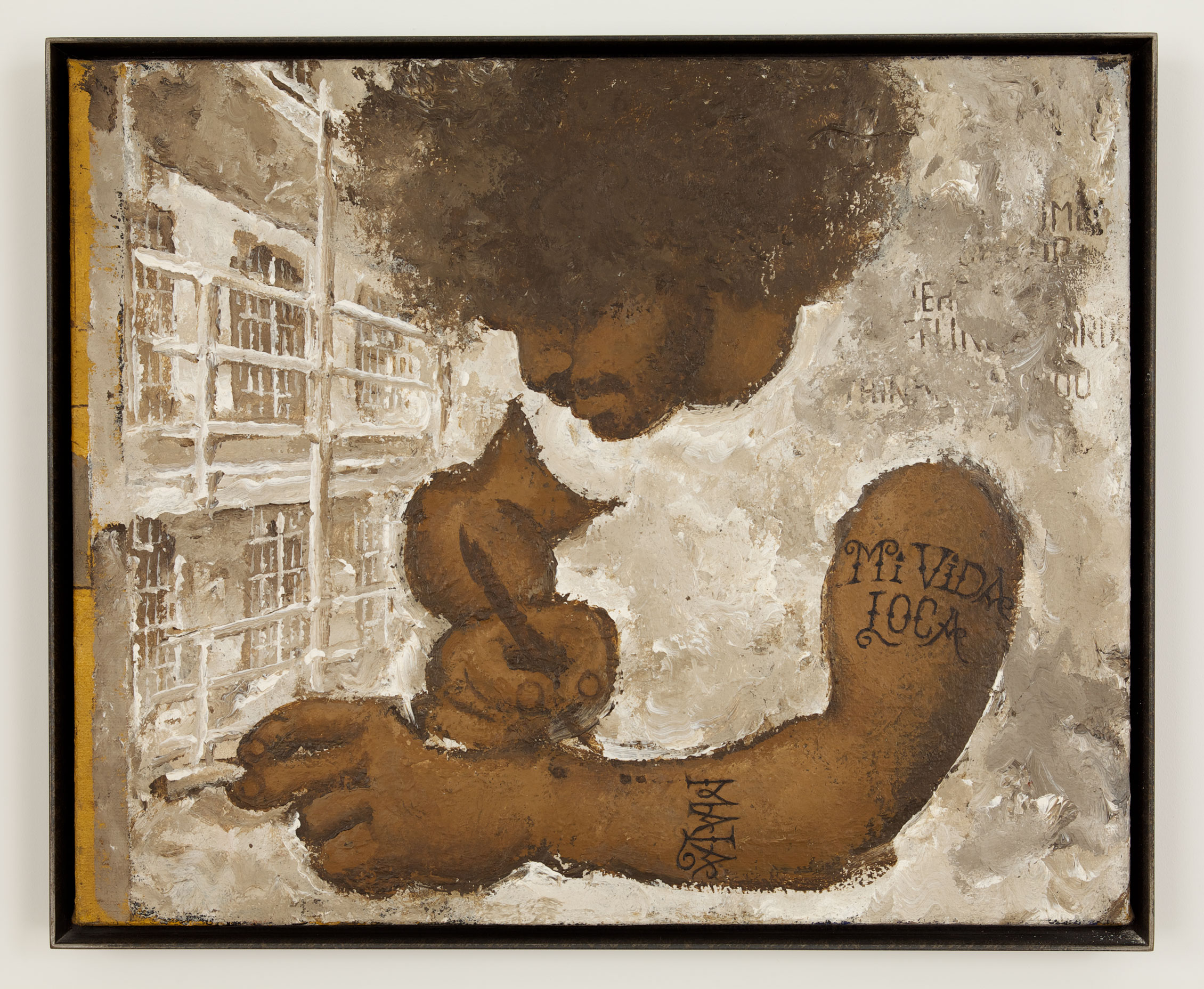

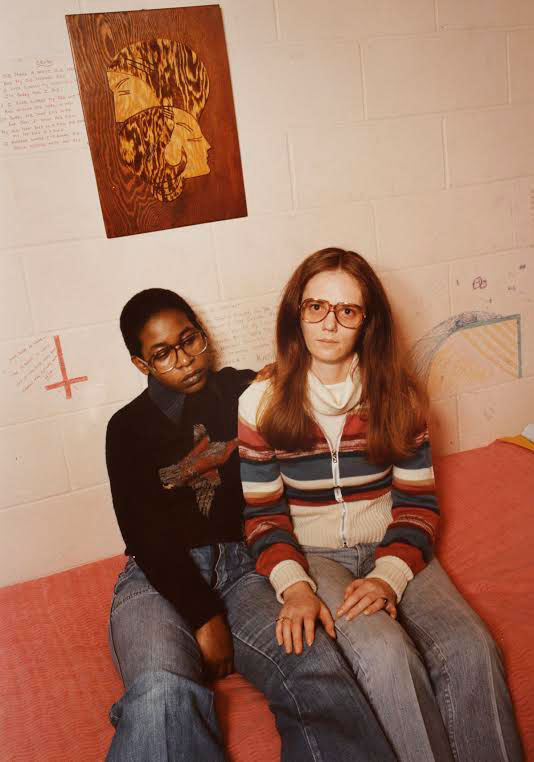

This show has an unfortunate relevance despite being nearly a century old. It’s obvious under Trump’s America, but even the “progressive” candidates are preaching hegemonic beliefs about the penal system. Was this a part of your thinking around the show? When I first read You Can't Win, I didn't think about its social and political implications or what it was saying about the country. It was just a rollicking-good history of a thief and a proto-Beat. It appealed to me also because it was mostly set in the West, where I grew up. But the older I got, the more it began to resonate, as a prescient and prophetic document about structural inequity in America, about hypocrisy and legal chicanery. Much of the book is about Black's stints in prison and the brutality of the system at the beginning of the 20th century. And so as the show evolved, mass incarceration—the corporate development of the prison system, the New Jim Crow, the activism of people like Bryan Stevenson—came into it, in direct and oblique ways. I'd say that almost half of the show ended up being "about" prison.

Can you speak to the ways in which you looked at 20th-century subjugation in curating this show and the ways its changed or has stayed the same? Black was poor. Most of the people who figure in the book are equally poor and desperate. Black was white and male so he was in a far better position than many, simply by virtue of birth. His story functions, in part, as a yardstick for how much worse so many other people had it in that period, not far removed in time from slavery, during the height of Jim Crow, before women could vote. Of course, progress has been made on many fronts since then, but structural economic inequality is just as bad now—in some parts of the country even worse.

"Not long after Black’s book was published, the share of wealth owned by the top .1 percent of Americans reached nearly 25 percent, its all-time high before the collapse of the Gilded Age; the share is once again approaching that level. The top 1 percent now hold more wealth than the bottom 90 percent combined" (Fortnight Press Release).

How do you put together a show like this without falling into nostalgia? I think I'm biologically allergic to nostalgia, in literature and art. I tried very hard to keep any sense of it out of the show, mostly because no one should feel nostalgic for the kind of life Black led, or the country that fostered it.

You Can’t Win and Presidio both deal with anonymity in a way. Is that even a possibility today? Does it matter for artists? If there's any nostalgia in the show, it might be for the notion that there was a time when people could substantially erase themselves from society, when complete anonymity was almost possible. Of course, that's no longer the case. Even the kind of personal privacy that was still possible only 20 years ago has moved beyond reach. And so I think there's a growing longing—which has been reflected in the art world in books like Broken Manual by Alec Soth and How to Disappear in America by Seth Price—for a sense of anonymity, which feels like a luxury that only the wealthy can now afford. A lot of the works in the show are about this longing. I also included a copy of Akiko Busch's great new book How to Disappear: Notes on Invisibility in a Time of Transparency, a kind of manifesto for a new sense of personal autonomy, resistance against a late capitalist system that is rapidly converting our lives and relationships into monetizable content-generation sites. She writes:

It is time to reevaluate the merits of the inconspicuous life, to search out some antidote to continuous exposure, and to reconsider the value of going unseen, undetected, or overlooked in this new world.

"You Can't Win: Jack Black's America" is on view now through August 18th at Fortnight Institute.