As a collector, I have always had a thing for art that involves hot dogs. I’m sure Freud would have something to say about it, but I just find it funny. From Lichtenstein to Oldenburg to Wurm to Blalock. I stopped dead in my tracks the first time I came across a supersized Ivy Haldeman hot dog.

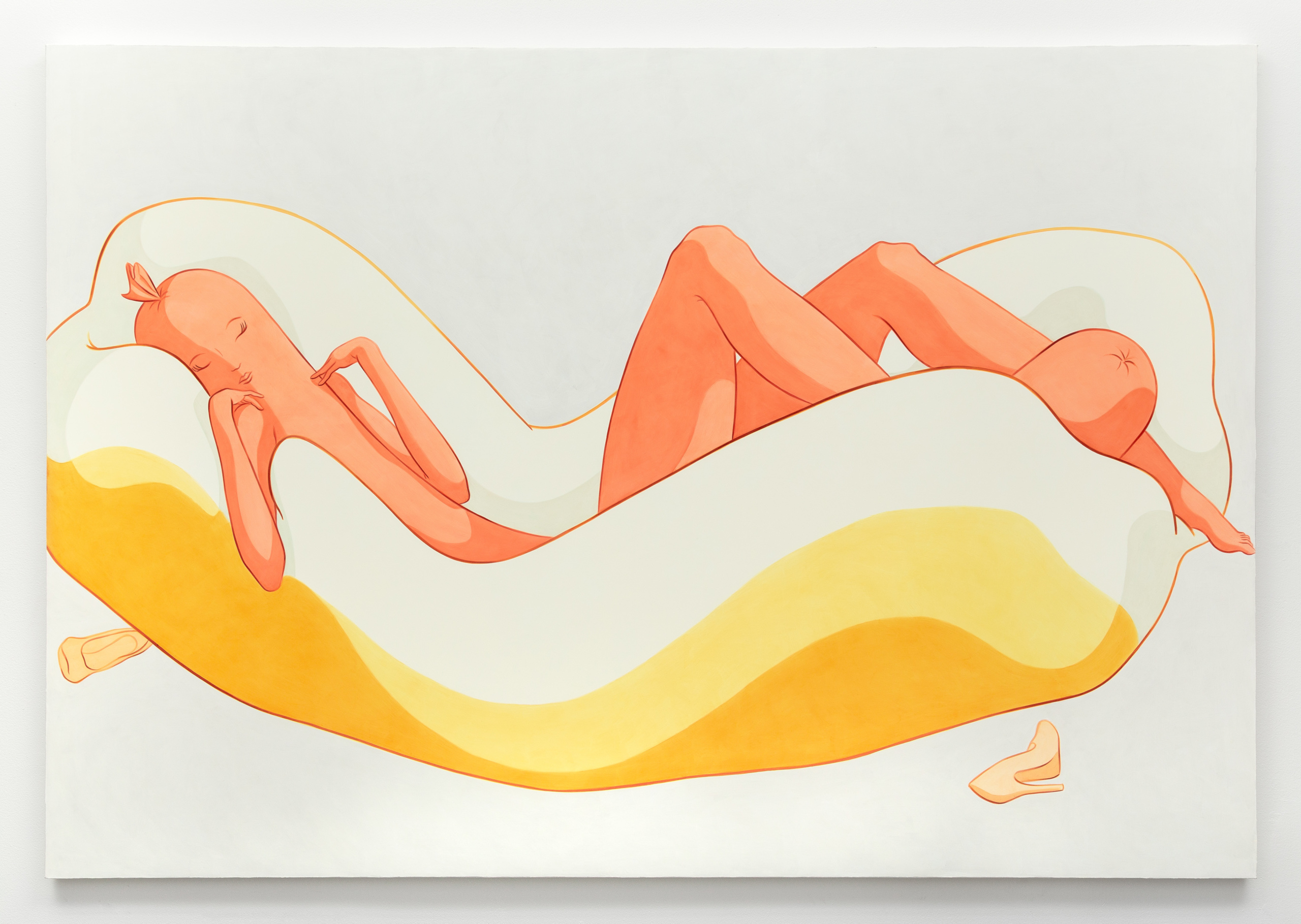

It was at the Downs & Ross booth at an art fair nearly five years ago. There she was, luxuriating on a supple bun. Sinuous eyelashes worthy of envy. Perfectly pointed ballerina toes. High heel shoes on the floor. She was chic. She was luminous, a bit like stained glass. She was sold. Ivy Haldeman has since emerged as one of the most coveted painters with works in the permanent collections of both the ICA Miami and the Dallas Museum of Art. The 35-year-old New York-based artist is gearing up for her May show at Downs & Ross, working nonstop in her temporary workspace, the 11 x 31’ hallway of a TriBeCa studio, surrounded by large hot dog friends.

“A painting is compelling company,” she says, adding that she wants people to develop their own conversations and desires with her work, “making a painting is really a live and let live situation.”

The hot dogs came to her years ago in Buenos Aires. She stumbled upon a hand-painted deli ad of a stiletto-clad hot dog on the side of a building. She sketched it and came across it years later in a pile of memories. Thus began her statement on form and identity, developing a practice that she describes as “the clearest expression of my soul. It gets it right in all its details.”

The artist is inspired by Kitagawa Utamaro’s print series, Twelve Hours in Yoshiwara, depicting 18th-century Japanese courtesans, and notes that her favorite image is of a woman who has woken up in the dark and is holding a candle to sleepily find her slippers. “There is something in this keen attention to the quotidian that is essential. These women are always being seen; they are always working.”

That is the essence of her figures, be it the hot dogs, or the iconic headless, hip-cocked pastel suits that effortlessly grace other canvases, like a mix of a Robert Palmer video and Working Girl. Technically, her work is a culmination of eight layers of titanium white paint at the base. “Titanium dioxide is a storied pigment,” she explains. “They put it in candy to make it opaque; they put it in sunscreen to block or reflect the sun.” Over the titanium comes transparent color upon transparent color. The light reflects off the titanium, giving the work a delicious brightness. “I want the work to feel open, like a window or a screen,” she says.

Haldeman began painting as an undergrad at Cooper Union (her mother is an artist, so it runs in her blood). She began taking her practice seriously after a chance encounter with Joyce Pensato at a laundromat, the Bean & Clean. Pensato sat her down and gave her some advice. “Joyce told me that if I was going to be an artist, I couldn’t put anything before my studio. It had to be the first priority,” recalls Haldeman. After college, she remained in New York and worked for Annie Leibovitz. “She showed me the value of time and unyielding discernment,” says Haldeman, who also credits her time nannying after school for reminding her to stay playful.

“Ivy focuses specific attention towards inherited poses and postures as foundational to immaterial assertions of aspiration, gender, availability and professionalism,” says her New York gallerist Tara Downs, who is giving Haldeman her second solo show at Downs & Ross (François Ghebaly represents Ivy Haldeman on the West Coast). She continues, “Her landmark hot dog paintings advance a new language for portraiture, one of impossible, fragmentary, or absent bodies both irreducible to the determinations of race and gender and critical for speculating new imaginaries through and beyond them.”

When asked what she will work on next, the artist laughed and would only say this: “Rumblings from other continents.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.