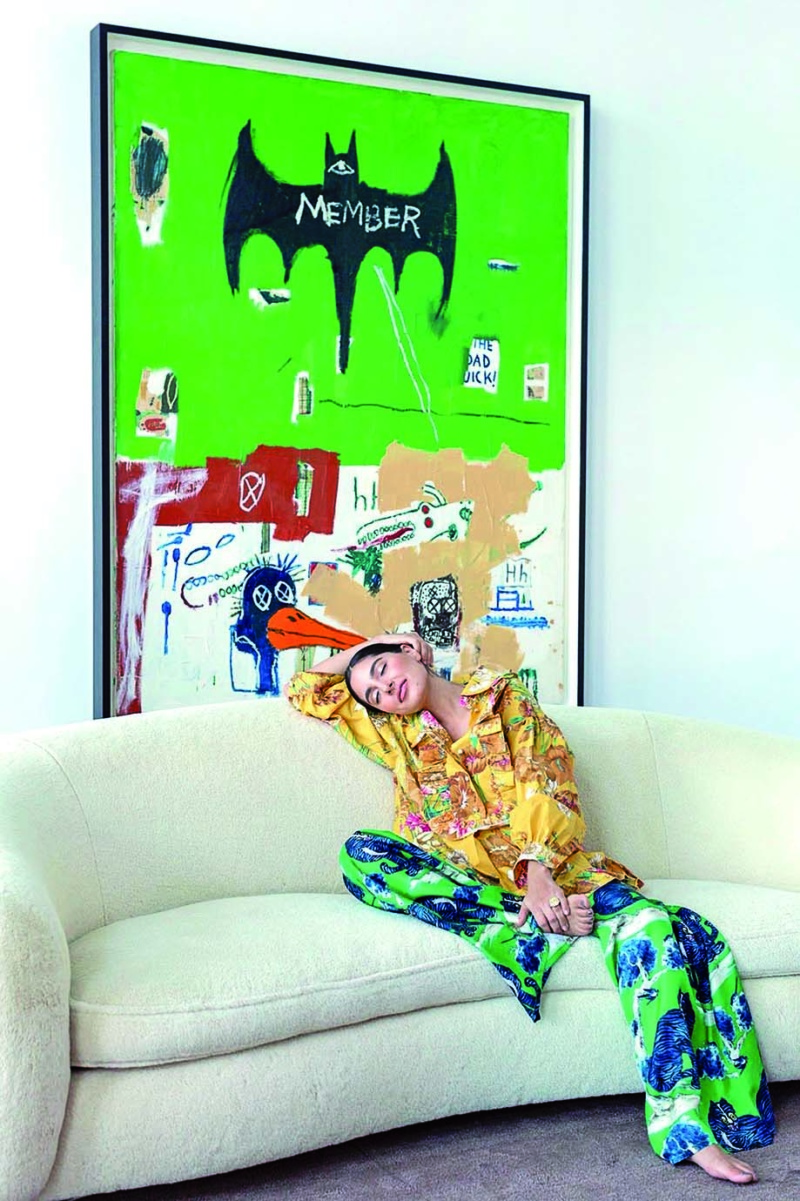

Laura Harrier, Los Angeles When Laura Harrier lived in New York full-time, she was a regular gallery-goer, frequenting the Lower East Side to see her friends in action. Now, the actor lives, at least mostly, in LA, where she’s spent the past two years shooting and overseeing the renovation of her new home in Silver Lake. She confesses that during the filming of Hollywood, her new Ryan Murphy-directed Netflix mini-series, her exhibition- going tapered off, but she is resolved to get back on track. The reboot plan? Her childhood best friend, independent curator Gavin Runzel, who has been an art world key-turn for as long as the actor can remember. “They don’t necessarily make it easy for new people to get involved, so Gavin’s experience has been critical to my own engagement,” Harrier says. “She’s helped lead me to discover new artists, pointed me towards shows that would challenge me and helped guide me towards individual works I might be attracted to. I don’t know how to go about it on my own.”

Friendship is the leading narrative behind Harrier’s collection and, as a result, it has a kaleidoscopic sheen. Its wild tapestry is composed of dissident threads including family heirlooms, gifts from talented friends and a strong vein of photography—a medium Harrier has always appreciated, thanks to her own vocation. She believes in the power of conjuring images and appreciates the craftsmanship that goes into creating a world that feels total. During our conversation, she calls out her experience shooting with Spike Lee for BlacKkKlansman (2018) as pivotal to her understanding of cinema as a technical art. Harrier finds heroes in those storytellers and visual artists who bring regality to the narratives of individuals who have been previously sublimated. She is doing some of this myth-making herself, as Camille in Hollywood, which revises the entertainment industry’s “golden era” with 2020 values. “What if a young black writer could have made a major motion picture with a big studio? What if Dorothy Dandridge had won the Oscar? These are the stories we are playing with,” she says. She sees the potential to be a part of similar shifts IRL.

“The arts are doing a good job of opening the doors, but I think part of the discussion has to be financial,” Harrier says. “I’ve loved being able to pick up things here and there without paying a small fortune. Galleries need to get the word out there that art is available for more than just millionaires. We all need to be part of that message.”

Leslie Amon, Paris It came as no surprise that a fashion designer like Leslie Amon, whose glamorous swimwear line has become a favorite of the jet-set and part of my fantasy vacation wardrobe, has a sweet tooth for figurative art. But I did crack a smile when the Parisian, dialing from her parents’ home in Switzerland, described her taste as “pornographic,” with a laugh. My mind races to Aspen, where I once saw a life-size, full- bush Cicciolina billboard by Jeff Koons looming over a collector’s dining room. Her example? A beloved set of six nude drawings by Matisse. “I love the way he pursues the line of the female body,” she says. “It’s a pleasure.”

A graduate of Central Saint Martins, Amon has her own hand, which she uses to bring her bombastic beach silhouettes to life each season. It’s perhaps this closeness to the practice that has ultimately attracted her to the figurative canon, from Egon Schiele to George Condo. But this is not to say that she doesn’t trade in her own generation. She cites Salman Toor and Julie Curtiss as wish list standouts and praises Claire Tabouret (she owns one of the painter’s latex mask compositions).

I ask her if the frenzied markets around newcomers like Toor and Curtiss add to a sense of urgency. “No, it’s a turn-off, to be honest,” she sighs into the phone. “When it comes to collecting, I think the best advice is to be curious and courageous in your purchases. I don’t like the idea of following the crowd. What’s the point?”

She credits her perspective on art to her late uncle, Maurice, a collector in his own right. “He had a spiritual connection to art,” she says. “He gave me that joy and the desire to live around and appreciate beautiful things.” But while very appreciative of his legacy and the impact it had upon her own philosophy, “collector” is not a title that Amon naturally ascribes to herself. “It’s something I’ve almost discovered about myself,” she says. “It wasn’t till my walls were filled up and I had friends over that I began to see it through their eyes.”

Joe and Kristen Cole, Dallas “We don’t collect assholes,” Kristen Cole, president and chief creative officer of luxury boutique Forty Five Ten, tells me. “We are friends with almost every artist we collect. It’s personal for us.” Kristen and her partner, Joe Cole, have been buying art together for almost a decade, and their collection is an evolving testament to their joint taste.

Never tempted to involve an advisor, the Coles have let their personal and professional network be the compass for their purchases, alongside their own intuitions. When asked to describe their predilections, Kristen notes that the couple tends towards bold, bright, often abstract gestures with Kevin Beasley, Katherine Bradford and Katie Stout sticking out as ready examples. Their acquisitions are helmed only by an annual budget, which helps them prioritize. “There are always about ten things we are following, whether an artist or a series,” Kristen says. This wish list lives between the Coles in text messages, emails and conversation.

Operating between Dallas, New York and Miami, in parallel with Forty Five Ten’s growth, the Coles have enmeshed themselves in fundraising for both international and local institutions. She praises the Contemporary Austin, the Blanton and Dallas Contemporary as entry points for discovery, including role model cultivation. She calls out Howard and Cindy Rachofsky, whose warehouse-style private museum is filled with ambitious sculptures and installations. “I don’t have any interest in collections where the premise is ‘look at my return on investment,’” Cole says. “I’m attracted to ones that are specific and thoughtful, ones that are tailored to the people who live with them.”

The Coles’s current fixation is on video art, an interest that has manifested in a project for Forty Five Ten. With the help of Cultural Counsel, the store commissioned ten young artists to create videos. Not all of them were necessarily filmmakers—Margaux Ogden, for example, usually paints abstract compositions riddled with small poems. Forty Five Ten has a long history of partnerships with artists. The one emblazoned in my mind is their 2019 collaboration with the Whitney, for which Caitlin Keogh created a limited run of shirts to fund-raise for the museum and two new paintings for the New York shop. Whether it’s with friends in art or friends in business, the Coles work better by keeping it in the family.

Lizzie Grover & Sean Rad, Los Angeles Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Alice Neel, Diane Arbus, Jasper Johns, Mary Corse: Lizzie Grover and her partner, Sean Rad, describe this cadre, their collection, as a place for “disrupters.” “We like artists who talk about the things that others are afraid to touch,” Rad clarifies. The founder of Tinder, he is a disrupter in his own right. “And, we learned early on that Lizzie has a higher threshold for darkness.”

Grover laughs. I imagine them seated together on a designer couch. The dog storms in, post-walk, his tail thumping through the receiver. An interior architect, Grover’s affinity for and expertise in art and architectural history was a galvanizing force in their nascent relationship. As they grew into their partnership, art offered a common space for sustained growth and conversation. “Early on, we got some incredible advice not to buy anything for the first two years but just to sit back and learn,” Grover says. “We had friends take us to shows and museums and pretty much walk us through the whole art world. We quickly learned about each other’s tastes, and our own, and that experience of looking at art without the pressure of needing to buy something allowed us to hone in on a perspective that we can both find meaning in. It helped us take a gigantic wish list and dwindle it down to something authentically us.”

When it comes to their recent contemporary education and discoveries, Rad and Grover give their advisor, Ralph DeLuca, the bulwark of the credit. “He was the first to ask us what we were interested in rather than trying to force feed us artists from galleries he was friendly with, or the new flavor of the month,” Rad says. “He is our coach. Everyone needs a coach.”

Their advice for new collectors on the lookout for an advisor? “Find someone you trust,” Grover says. “It might take a while to shop around, but it’s worth it.”

Maky Hinson, Miami Miami’s art scene has been shaped by its major collectors: Pérez, Cisneros, de la Cruz, Rubell, Margulies. But, upon revisitation, it’s the potential of the city’s vanguard that floors me. Maky Hinson is part of this budding class. The jewelry designer and mother of two is a fixture on the art and fashion circuit, a voracious collector and a member of the ICA Miami’s acquisitions board. When we speak, Hinson apologizes for answering slowly. The bilingual collector charms me with her vagueness, which is careful, not hollow, often trailing off into the hush, like a romantic poem spoken by a sleepy movie star. “I look for art without an agenda,” she says. “Good work speaks to you—you just need to be in the mindset. My greatest asset in collecting has been my open mind.”

Working with an advisor for the first four years, Hinson now buys work as the occasion arises. “The advisor was helpful when starting out, but I would recommend doing the work yourself, get invested, see as many exhibitions as possible,” she says. “It adds new layers.” She prioritizes viewing art in her daily life, often roping her family into it.

Hinson’s parameters for purchase are open-ended, but tend towards the blue-chip and painterly with Cy Twombly, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Josh Smith highlighted as she drifts to first. More recent purchases include a new Calvin Marcus painting and a Kathleen Ryan sculpture, picked up at Art Basel Miami Beach and Frieze Los Angeles, respectively. Art fairs are an important place for her search process. She often takes her husband and does a full lap before digging in. The act of looking is the pleasure for Hinson.

Her vision comes through most directly with Caraluce, her jewelry line with Rachel Korine. Boasting chunky, cinematic gold bracelets and chokers, its decadence speaks to Hinson’s subverted playfulness. Like the painters she admires, she revels in materials called into bold action.

Larry Milstein, New York I can see both Central Park and Lincoln Center from 25-year-old philanthropist and real estate heir Larry Milstein’s apartment and I think I might faint from jealousy—Philip Johnson looks almost toy-like from so many stories up. I can’t be green for long though, because Milstein’s optimism is infectious and I’m easy. Besides, there is genuine excitement to be had as we puzzle through a beautifully drawn instruction manual for a glossy, rainbow balloon Jeppe Hein sculpture, an Art Basel Miami Beach purchase finally arriving for install.

He and I are meant to take a short, “behind the scenes” video for the magazine’s Instagram feed and Milstein’s on top of it, snapping on a blue latex glove and mounting the ladder to affix the magnetic belly button to the navel of the fake inflatable. I got a short video with my iPhone, Grimes’s new album playing in the background. An intuition for this kind of gesture is foundational to PRZM, the Gen-Z luxury brand consultancy Milstein cofounded and, moreover, to his approach to seeing through real social change. Milstein is an active fundraiser, and often partners with his sister to pull off large-scale benefits, including the Vanity Fair-covered Millennial Pink Party in the Hamptons—an event thumbing its nose at the Trumps. He is a huge believer in the deals one can nab during charity art auctions. “It’s really about having an eye and doing your homework,” he says, with a smile. Milstein’s eyes are peeled for work that speaks to the narratives of his generation and those overlooked in less-woke eras. “I think it is your obligation to collect your peers and to promote the stories of those who have been previously suppressed, specifically queer, POC and female narratives.”

The work in his apartment that catches my eye is a small but powerful Manuel Solano portrait with a poppy red background and frame that reminds me of a Sarah Charlesworth, in the way that its intense saturation slices reality into a flat plane. This work is a favorite of Milstein’s, and one whose purchase he shared on Instagram, penning an elongated caption with the biographical story that had captured his attention. “As a collector it’s not only your job to educate yourself, but to go out and share that knowledge,” Milstein remarks. “We need to be creative about what those pathways are. It’s not enough just to be in your own space with work—you need to get out there and engage your peers.” His Solano post elicited a major outpouring, including from the artist himself, who reached out to Milstein to thank him for passing it on.

Tina Perry and Ric Whitney, Los Angeles A shared love of art is fundamental to Tina Perry and Ric Whitney’s romance. I can actually feel the mutual admiration radiating between the LA-based collectors when they meet me in the lobby of their hotel. They are in town for the Armory show, where Perry helped award a booth prize to Portland’s Upfor for its presentation of artist Julie Green.

“I always knew I wanted to be a collector, but I didn’t know how to start,” says Perry, president of the Oprah Winfrey Network. “I was working in New York and it seemed impossible. When I got relocated to Los Angeles and started going to exhibitions, it felt like it could happen, but the defining moment came when I met Ric and he shared the same passions; that is when it became real.”

Almost ten years later, Perry and Whitney are even deeper in it. In 2014, Perry founded the alternative LA art space, The Mistake Room, opening the door to a broader definition of patronage—one that squared with Whitney’s own first forays into art: supporting talented friends by any means necessary. “For us, patronage is a large umbrella that covers all the ways you can support the arts, and collecting is still a very small segment,” says Whitney, who runs two companies, one handling talent management and the other, music publishing. “We’ve been lucky enough to become collectors over time, but we came to the arts first as patrons and we see that mission as something that includes conversations and attending exhibitions. Artists don’t just need buyers; they need support for the work in many different ways.”

Nurturing up-and-coming careers has become a thrust of Whitney and Perry’s collection. “Because it is so intertwined with our relationship, there is an inherent beauty and a love that is foundational to the way we collect and that extends to the artists we bring into it,” Perry says. These days, Perry and Whitney have found themselves particularly attracted to the work of Genevieve Gaignard, Sayre Gomez, Deborah Roberts and Vincent Valdez, but their overall collection is omnivorous, crossing mediums and continents. Emblematic of the discoveries they’ve made together, the burgeoning treasure trove has been accumulated without compromise. “We don’t do trades,” Whitney tells me. “We both have to love a work before we acquire it. Of course, we are both always up for the discussion.”

Michael Sherman, Los Angeles Film producer Michael Sherman’s introduction to art wasn’t exactly smooth. His first rodeo, Art Basel Miami Beach, administered a prick of reality. “No one would sell me anything,” Sherman says. “I didn’t realize yet that galleries were gatekeepers.” His only souvenir from the experience, a Jon Pylypchuk work purchased from Fredric Snitzer Gallery, still occupies a prominent spot in his Los Angeles home. Seven years later, livability is still the deciding factor for Sherman and, in this way, his collection skews toward those domestically-scaled mediums: painting and ceramics. “If I don’t love it, I don’t buy it,” he says. “I don’t buy things to own a certain artist; I buy things to live in my house.”

There are exceptions. In addition to wall- bound works by Harold Ancart, Sue Williams, Lauren Halsey and Noah Davis (a favorite), Sherman has bitten off whole installations, including a massive snake piece by Elaine Cameron-Weir that, to his chagrin (and mine), does not fit in his living room. “I remember seeing her frankincense clamshells at Ramiken Crucible in New York, and thinking that it was the coolest thing ever that someone would doctor something as humble as a shell and make it into something that acts as a shrine.”

As a collector, Sherman reminds me of a birder. He loves the act of looking, ritualizing exhibition-going on top of serving on the Hammer’s board. And, as does any true Audubon, he is also an admirer of the exemplary and the rare. He hunts with a local bent and places an emphasis on artists who engage the fantastical world of entertainment that he occupies professionally.

Sometimes the interest flows both ways, as revealed by the story behind his massive Rashid Johnson, which followed a collaboration with the artist on his 2019 feature film debut, Native Son. “I had always admired him as an artist, but for a first-time filmmaker, I was blown away by the pre-production due diligence Rashid had done,’’ Sherman notes. Their first picture was optioned to HBO during a lauded Sundance run. A second feature film is in the works. And it’s not the only artist project Sherman has up his sleeve.