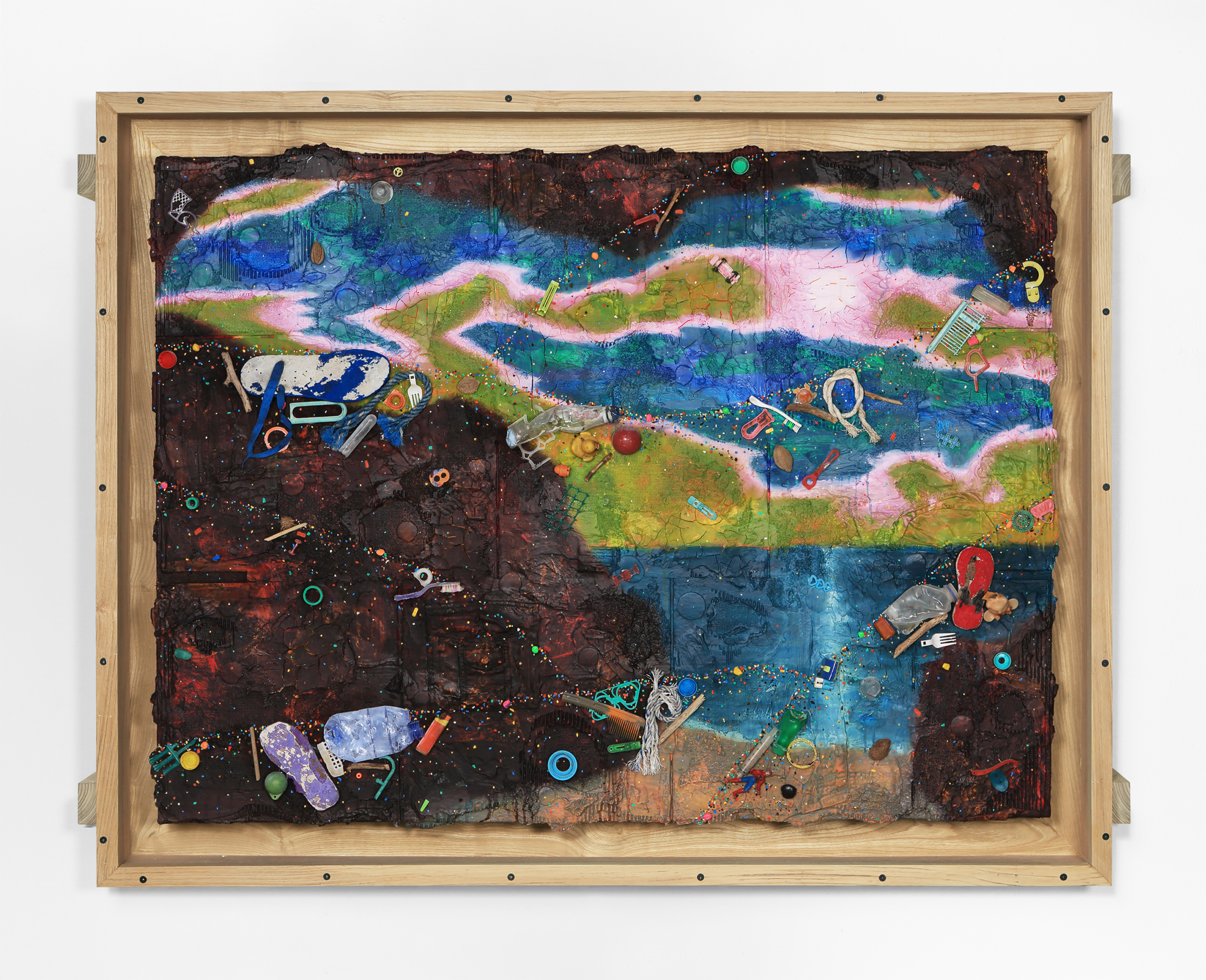

“The first myth you have to dispel is that I live in some kind of a Gauginesque paradisiacal fantasy,” Ashley Bickerton tells me over Zoom from his home in Bali. Though he has called the island home since the early nineties, COVID-19 has brought out some deep-seated contradictions. “In the expat community and the surf world here,” he says, “it’s maddening because there is definitely a racial line with masks. The white foreigners believe that COVID-19 protocol is only for the brown serving classes. I don’t know if it’s because of my Indonesian family or growing up as I did, but I find it intolerable. I boil when I see the imperious entitlement of this neocolonial indolent class.” A suite of new paintings currently on view at Lehmann Maupin likewise reflect this desire to puncture idyllic illusions. Called the “Flotsam” series, they consist of seascapes and landscapes covered in detritus that washed up on the shores in Bali: flip flops, lighters, plastic water bottles and the like.

The show came about as a result of the cancelations and problems created by the pandemic. Bickerton originally had a double show scheduled for Lehmann Maupin and Various Small Fires in Los Angeles for February last year. “It was going to be my umpteenth comeback,” he explains, “and COVID threw a wrench in that.” The work itself, however, grew out of an earlier series of sculptures, the “Vectors,” which likewise incorporated beach detritus, first exhibited at the Newport Street Gallery in London (“Damien Hirst’s private museum,” he wryly comments) in the exhibition Ornamental Hysteria in 2017. The show presented a chronological survey of Bickerton’s career with a final room for new work. Hirst told him, Bickerton recalls, “This has to be the best thing you’ve ever done.” So, “I had to make the best work I’ve ever made on call, which everyone knows is impossible, but it was tempting and it was a challenge.” He found it down at the beach one evening in the patterns of detritus and the lines of the receding tide.

“It fit so much into the vocabulary that I’ve established over the years,” he recalls. “The organic carrying all these cyphers, all these signals, these residues of lives lived, of human narratives, discarded relics of childhood. Particularly poignant for me are the one-use things, like those plastic clips that go into your clothing when you buy them, and you pull them out and throw them away immediately, and that’s all they’re ever made for. And they’re issued out of the anthroposphere into the biosphere for eternity. There is a dark poetry there that I found somewhat exquisite.”

Even as he created subsequent versions of the “Vector” boxes, they seemed to call out for chromatic elements, and he decided to return to the original eureka through paint. “When I saw the wave lines on the beach,” he says, “I knew it was a path to follow, but what path? There are so many ways to approach it.” The first one he did was on raw canvas, but he wasn’t satisfied because the canvas is the color of sand, so “it looked like a model of the real thing.” He wanted something “more poetic, more discursive, even more mystical.” Then he tried abstract backgrounds of morphing color, but that didn’t work either. “It’s hard,” he tells me, “to make the objects and paint mate properly.” He made his way through every imaginable kind of paint and application. “I knew I had something,” he says, “I knew I had to nail it. I worked through so many variations.”

There was also in the question of presentation. At first, he put them behind glass. He had, he says, a somewhat cynical reason: “Your job is to find garbage and put it in collectors’ homes and they’re going to pay you good money for it. So, by putting them behind glass, they become a museum specimen. It’s a distancing device.” But he decided to ditch the glass, and instead “pick my objects carefully, have fewer objects and key up the backgrounds to bring them in to play more.” This then led to a building up of the backgrounds by incorporating cardboard, discarded clothing, thickening paints. “It’s like pushing paint through cracks and rough terrain,” he says. One element that stuck early on: “the earth sky binary—blue sky and brown earth.” For this effect, his inspiration was Dali, Miro and Tanguy. But he also came to draw heavily on the visionary American modern landscapes from Milton Avery, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Marsden Hartley: “Not a depiction of an actual place, not a mirror of the world around. It is a psychic trigger for experience.”

In fact, he says, he “stole liberally from those guys,” likening it to a musician playing a cover. “I’m not a libertarian by any means,” he explains, “but I think I am in art. I hate to say that because after the debacle of the Trump presidency and the hell we’ve been through with COVID, libertarianism has a stink about it and I’m somewhat repulsed to use the word. But I might share some if their philosophies when it comes to artmaking.”

The final element of the Flotsam paintings is that they are framed in shipping crates. “It’s a little bit arch-,” he says, “because they don’t actually work as shipping crates.” In fact, the show was delayed several times because of problems with shipping. Bickerton was pretty sanguine about it though: “What am I gonna say? That we should deny vital medical equipment and vaccines during a pandemic so we can transport baubles for the plutocracy.”

Complicating the entire process of organizing the show is that Bickerton has been dealing with pressing health problems. He is suffering from spinal stenosis, a deterioration of the nerves in the lower back. He now walks with a cane and finds it increasingly difficult to go up and down steps—and he lives on top of a steep hill. Although he’s tried every therapy he can, “there is very little you can do during COVID on the island of Bali,” he explains.

The illness came on slowly: “I noticed I couldn’t twerk in my forties. I couldn’t do my impressions of Madonna rolling around on the ground. I could still surf, I could still do everything else. I just thought it was aging.” But then, during several months in Los Angeles at the start of the pandemic, he noticed physical activity starting to get harder. “I could still push a pram up the hill to Griffith Observatory, so I thought I’m okay. Now I realize pushing a pram up a hill like that at 60 probably isn’t great for your lower spine, even if people look at you say, ‘that guy’s tough, pushing his granddaughter up the hill.’ When in actual fact I’m pushing my daughter and I’m not tough, I’m broken now.”

Back in Bali in July, the real shock came when he was out surfing and couldn’t stand up on the board. “For anybody who’s surfed their whole life,” he explains, “you don’t think about it. It just comes naturally, it’s like breathing.” Friends paddled over and looked at him with “a mixture of surprise, pity and abject horror.”

“If I never surf again,” he says, “I’m okay, even though I have spent my life doing it and it’s one of my great loves. I’m fed up with surfers; they’re bunch of fucking idiots, and I don’t say that lightly after this pandemic.” More challenging is that between all the therapies, he only gets to the studio for a couple hours a day.

He seems optimistic, however, and is eager to move on to new projects. When I ask whether the detritus was all really found on the beach in Bali or whether it was more like the shipping crates that aren’t really shipping crates, he assures that it all—well, almost all of it—was. There was a bit of “the hand of God intervening.”

“Very early on,” he recounts, “I realized there was fundamental bifurcation in thinking in art, exemplified by two friends of mine. On one hand, you had Jeff Koons who took the basketball, and it actually had to float. It has to be what it is. And on the other side, you’ve got the likes of Damien Hirst. He’d split a cow in half and stitch it onto clear plexiglas with nylon filament, suspended in certain ways—so it was about the theater of what you’re seeing. I realized that I’m very clearly on the second side. I don’t really care if it is what it is.

“I’m telling a story,” he says. “It’s art. It’s not a science project. If art hues too closely to empirical reasoning, it can be dull. Sometimes it has to take flights of fancy. It breaches a mystical divide, it opens up a portal to something possible.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.