In 1986 and 1988, Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York and Jane DeLynn’s Real Estate satirized the impossibility of finding affordable housing in New York and how this trapped people in troubling relationships. According to American psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs, shelter is foundational. Relationships come later. This was true for Janowitz’s and DeLynn’s characters, who settled for abusive, stale, and creatively stifling romances in exchange for a better view, more square footage, or a roof over their heads—period.

A majority of the characters in both Janowitz’s and DeLynn’s books were—like their authors—artists or art-adjacent. For decades, artists and their supporters have flocked to New York, among other increasingly expensive art capitals, from Berlin to London, Los Angeles, Paris, and Hong Kong, with hopes of forging a career and finding their people. For queer artists, cultural capitals have an even greater pull as they tend to be safer and promise better odds at finding sex and love. Given the proximity to so much wealth and industry, some artists strike gold in cities like these. For others, living in an art capital has become untenable.

Consider: The same New York apartment that cost $171 a month in 1975, and $550 a month in 1988, could now go for $3,397, the median rent for a studio circa May 2025. Even after adjusting for inflation, that means median rents have tripled since the mid-1970s and doubled since Slaves of New York became a bestseller. At the same time, median wages have barely risen—the minimum wage has actually fallen. According to the most recent study I could find (from 2017), three-quarters of American artists earned less than $10,000 off their art annually. That’s about three months’ worth of rent in a New York studio apartment.

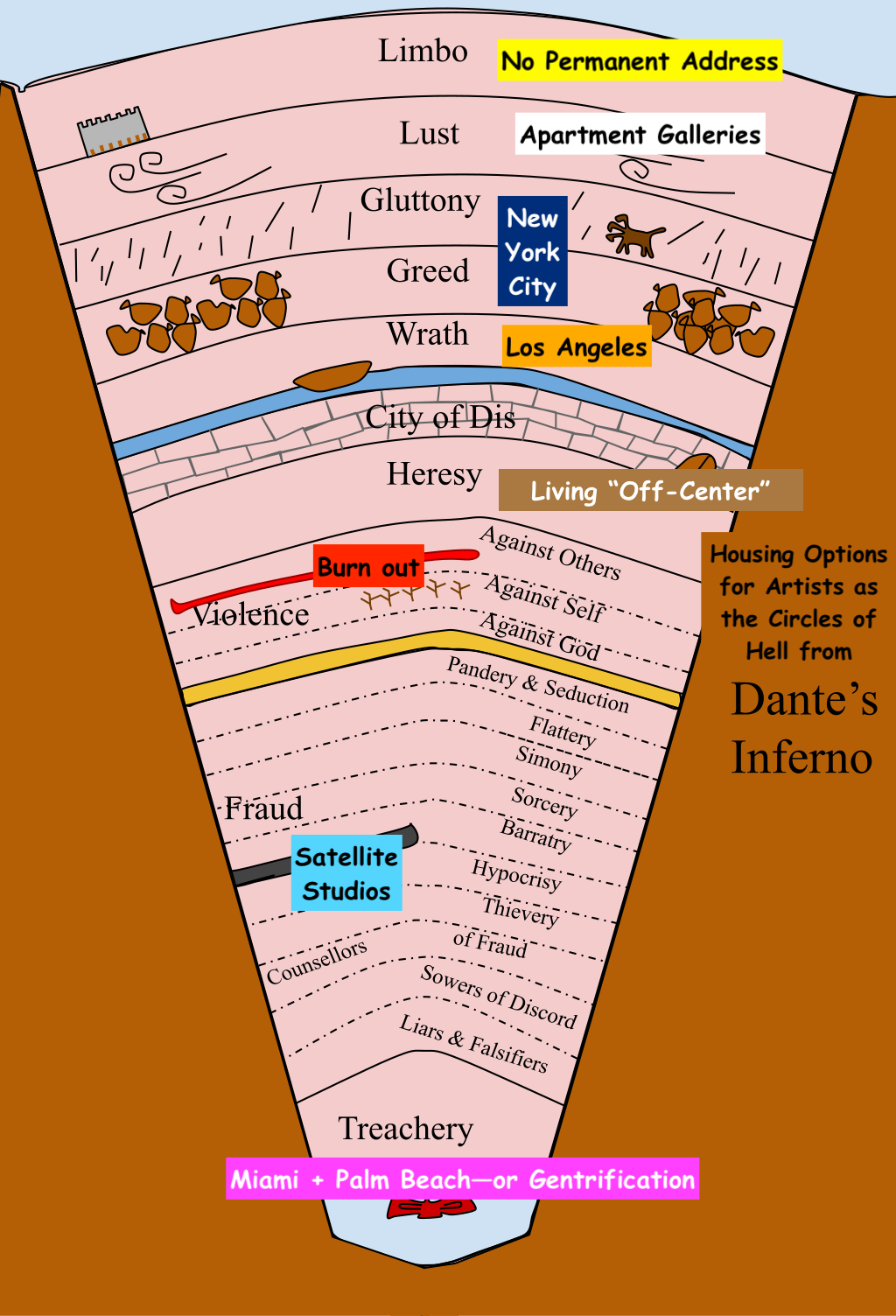

New York isn’t the only ever-inflating city, of course, and artists aren’t the only people suffering from a dearth of affordable housing in these places. However, artists offer an interesting case study. By definition creative, artists set trends, including housing trends (like loft living in the ‘60s and ‘70s). Alternative housing opportunities have also been created specifically for artists in the forms of subsidies and arrangements provided by the state, academic institutions, foundations, patrons, and collectives. Both uniquely valued by society and also disproportionately at risk, existing mostly outside of the social safety net, the artist’s way is one of precarity. As social welfare programs are eroded around the world, and A.I. upends jobs, more and more people may be thrust into the position that artists are in. How are contemporary artists contending with the affordable housing crisis? Have they found creative workarounds? The more I researched this topic, the more depressed I became. In the end, the only thing that could get me out of it was to make a meme.

The illustration I’ve presented above is not the only one that could be drawn, mapping contemporary artists’ housing options alongside the nine circles of Hell. I encourage others to make their own housing hell maps and compare. My knowledge is limited to my own social circles, as wide and eclectic as they are.

We begin in Limbo, the first circle of the Abyss outlined in Dante’s Inferno. It’s where, as his early 1900s translator Dorothy L. Sayers noted, “those who refused choice” and “those without opportunity of choice” reside.

When an artist seems to be everywhere, it’s possible they live nowhere. That is, they have no permanent address—except maybe their parents’ place or a P.O. box or a small room in a shared flat that they sublet. (“Subletting my room in Berlin from 2 p.m. on October 14 to 9 p.m. on October 19. Serious inquiries only!”) Maybe they have a storage unit or an art studio instead of a room, prioritizing a work lease over a domestic one. (If they’re lucky, they can secretly sleep there too, although usually, there’s no shower.)

One response to the lack of affordable housing in art capitals is for artists to bop between different paid, free, and cheap housing opportunities. “They’re piecing together a quilt,” Katerina Llanes, program director of the New Wave residency in Palm Beach, Florida, explains. “I’m doing a residency here, then I have to go to this art fair, then I’m doing this project here… Honestly, half of the artists I encounter are living this way.” The mix can include paid residencies like New Wave, home or pet sits, sublets, collectors’s homes (empty or not), friends’ couches, and spaces associated with galleries and institutions, often offered around the time of an exhibition.

Shola von Reinhold’s 2020 novel LOTE charts this lifestyle to comedic effect. Her London-based protagonist, a queer Black ornament-obsessed archivist, begins a house-sit that she soon has to evacuate when the leaseholder returns early. She ends up crashing with a rent boy who lives for “free” in an empty property courtesy of a developer who has designated it as a pseudo-brothel until it’s time to sell. She can’t stay there, though—she’s femme, and the clientele likes men. She gets lucky when a paid residency agrees to advance her the program honorarium so she can afford a ticket to the obscure European town it’s in.

One counterpoint to von Reinhold’s novel is John Yuyi’s 2025 zine POV, which comprises a month’s worth of self-portraits taken while the photographer flat- and cat-sat her way through New York, Barcelona, and London. Yuyi has been living nomadically since 2022, when an exhibition brought her from New York to Zurich. With the contents of her studio tucked away in storage, the Taiwanese photographer has avoided paying rent ever since, traveling wherever she’s invited or employed, often waking up blurry-eyed and wondering, Where am I? Mexico, Berlin, Tokyo…

Living nomadically can be glamorous, invigorating, and educational. Facilitated by smartphones, social media, and affordable airfares (the costs of which have dropped at rates similar to those by which housing costs have risen), this hustle has never been more common. But a peripatetic lifestyle is also exhausting, and it can be unexpectedly expensive when, say, you need to ship work overseas or your free place falls through last-minute. If you have dependents, chronic illness, mental illness, disability, no passport, or other difficulties crossing borders—or if you value long-term relationships, or if your practice demands a consistent space—living in limbo can be treacherous.

In March 2009, as a Canadian undergraduate student on a semester abroad, I sublet a loft in Berlin’s Wedding neighborhood. The area, still one of the poorest in the city, is now home to Callie’s, a nonprofit residency and exhibition space. In 2009, art was just beginning to seep into this working-class and ethnically diverse area. My boyfriend was a professional gambler; he paid our rent. That March, he traveled to London and Paris to play poker, leaving me alone in our sublet, which doubled as a gallery. Installations, sculptures, and video art filled the large white loft, next to which was a small bedroom, kitchen, and bath. The show on view was about global feminism and included a video about dating training module in which Russian women were taught the art of the blow job with bananas and how to seem alluring by acting dumb. Just as I didn’t know at that time that having dessert for every meal could be bad for you, I wasn’t conscious that I was not unlike those Russian women—trading my sexual capital for subsidized rent and a joint bank account.

Are apartment galleries the purview of the young? Three notable ones from recent years have been run by 20-somethings. There was Cherish, founded in 2019 by Mohamed Almusibli (b. 1990), James Bantone (b. 1992), Thomas Liu Le Lann (b. 1994), and Ser Serpas (b. 1995) out of their shared living space in Geneva. The project ended in 2023. Almusibli is now the director of Kunsthalle Basel; Serpas, a famous artist. The second notable is a secret. (The gallery itself is public; it’s one of the best new galleries in America. The secret is that its young directors sleep on cots they’ve stored on site because they can only afford one lease between them, and it’s the gallery’s.) The third notable came recommended to me at every stop I made on my last European vacation. In Berlin, Paris, Marseille, and Copenhagen, everyone seemed to agree, London’s Galerina is “it.” No one mentioned that it was someone’s home.

Galerina’s Estonian founders, Mischa Lustin and Niina Ulfsak, have day jobs: Lustin works at a bank and Ulfsak is director of Arcadia Missa gallery. After work, they come home to their “Segal house” and their second job. A Segal house is a self-built home designed by architect Walter Segal, “a utopian socialist model for social housing,” as Lustin put it. Previously, they occupied a council flat “where a lot of iconic artists used to live,” says Lustin. One is Georgie Nettell, who has since shown with Galerina. (They’ve also shown Hannah Black, Dan Mitchell, and Ewa Poniatowska.) Having grown up in social housing in Estonia, Lustin and Ulfsak are sensitive about the “potential fetishization” of what for them is a “purely financial” reason to exhibit there, while attempting to respect their neighbors by keeping the gallery open only to friends and vetted supporters, who often stay for dinner.

Apartment galleries are a home for new and under-recognized art. They’re often run by artists. Or, in the case of Galerina, by devoted community members. “We started,” says Lustin, “for the artists around us, all from immigrant backgrounds and without a physical platform to show work.” (They were the first to exhibit the now-popular Coumba Samba and Gretchen Lawrence.) When you’re open, limber, and eager, these kinds of live/work situations are romantic—sexy even. Charged. But when we age, is it sustainable? The fact that few apartment galleries are run by people past their first Saturn Return may tell us the answer. And that’s a shame because the lust for art that animates apartment galleries is contagious. They’re filled with work you’d actually want to live with.

It’s said that New York is fun hell and LA is shitty heaven. New York is fun, but it’s pay-to-play, spoiling and depriving artists at the same time. Home to more billionaires, investment banks, Broadway theaters, galleries, and high-value art auction sales than any other city in the world (not to mention the highest density of influencers), New York’s 50 percent share of the global art market is glutted with ambition, competition, innovation, beauty, debt, and disappointment. It’s so major, it accounts for two circles of Hell.

New York’s gluttony and greed struggle is often met with shrugs and schadenfreude. Just as our abundant trash (New York also ranks at the top globally in waste production) is shipped off to be burned and stored elsewhere, those who “can’t hack it” tend to leave, while those who stay often mask the very conditions that allow them to do so, whether that’s family money, living with no windows, or funneling half of their income into rent, as one in three New York tenants does today.

In 1986, filmmaker Lizzie Borden set her second feature film, Working Girls—now part of the Criterion Collection—in a Manhattan brothel based on the one she’d worked in to afford her first feature film, Born in Flames (1983). Other notable artists and art workers of Borden’s generation worked in that same brothel—they just kept it a secret. To this day, sex work is a way for some artists, mostly queer and/or femme, to make New York work for them. Among them is Sophia Giovannitti, who, following Borden’s lead, titled her 2023 autobiographical Verso book Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex.

Living with elders is another hack. For years, there was a legendary woman known as Suzie who you could call to pair you with an elderly Chinese person to live. You’d pay the unit’s rent in full, still a deal compared to Manhattan market standards. Many of Suzie’s elders lived in the parts of Chinatown now called “Dimes Square” and “Two Bridges,” recently gentrified areas made “cool” by an influx of models, skaters, and artists much like the ones in the Suzie network. Porcelain artist Sarina Lewis stumbled into an intergenerational housing arrangement after spending over a year walking the dog of an older woman who lived on the Upper East Side. “We’ve become really close,” Lewis told me. Pairing under-housed individuals with elders is a beautiful unicorn of an idea that promises to address both the affordable housing and loneliness crises—even if it is a Band-Aid. Perhaps it’s time for a Seeking Arrangements-type site for under-housed artists and the golden generation?

Artist housing, once a 20th-century experiment, is now the stuff of urban legend. Westbeth, New York’s famed Housing Development Fund Corporation (HDFC) cooperative for artists—created when the city reclaimed and sold abandoned buildings back to tenants—had become a naturally occurring retirement community by around 2006, with over 60 percent of residents over 60. Today, its waitlist is closed after stretching beyond 15 years, as Peter Trachtenberg reports in his 2025 book, The Twilight of Bohemia: Westbeth and the Last Artists of New York.

Artist and filmmaker Amalia Ulman recently purchased an HDFC apartment in a different building. She christened the place with a group show titled “MiCasa.” Works by Elizabeth Englander, SoiL Thornton, Maggie Lee, and Mitchell Algus were presented alongside wall drawings by the former tenants. Ulman, who grew up poor and working class in Spain and Argentina, has always been candid about money and class. She explained that, while HDFC purports to be affordable—and indeed, there is an income cap limiting who can buy into the cooperative—sellers often privilege buyers who can buy with cash up front. “Who is low-income,” Ulman asks, “and has hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash?” Ulman purchased her apartment with settlement money from a bus accident that left her permanently disabled.

But you could always apply for a grant. “We felt the best thing we could do was to give artists cash to help them pay their rent,” says Katarina Jerinic, an artist and the collections curator at the Woodman Family Foundation (WFF), which arrived at this decision in response to the prompt, “What is an artist’s greatest need at the moment?” Now in its inaugural year, the WFF Housing Stability Grant For Artists will give five New York City artists a total of $30,000 each over three years to offset housing costs. Managed in partnership with the New York Foundation for the Arts and the Entertainment Community Fund, the grant also offers award winners counseling on how to navigate New York’s opaque affordable housing system, including how to apply for housing lotteries. The WFF grant itself is a lottery, to which hundreds applied in the first year alone.

With mortgage interest rates hovering around 5-7 percent and rents rising, even the Wall Street Journal has started using the term “housing crisis.” A recent headline: “New York’s Housing Crisis Is So Bad That a Socialist Is Poised to Become Mayor.” This, of course, is Democratic mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, who is running on a platform that promises rent freezes on rent-stabilized apartments. Mamdani is married to an artist, Rama Duwaji, and his campaign received boosts from many figures in the arts, among them actor Hari Nef, poet Kay Gabriel, and art dealer Carol Greene. Mamdani won more votes than any other mayoral candidate in New York primary election history—but his bipartisan critics warn that his proposed tax increase of 2 percent on individuals earning more than $1 million a year will drive them out and ultimately make New York poorer. This debate seems to deliberately distract from the fact that big-time owners, not necessarily high earners, hoard the most wealth by evading taxation through clever manipulations of the law—and that’s already happening. Anyway! As the arts and culture sector contributes nearly $10 billion annually to New York’s economy, providing more than 300,000 jobs across related industries while establishing the city as a global hub for ideas and creativity, the artists soft-powering the city’s reputation are especially at risk.

In 2015, Los Angeles artist Julie Becker wrote the words “I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent” into one of her drawings (watering, 2015). A few years later, those words became the title of her posthumous retrospective. Becker died by suicide in 2016 while living in what her friend, the author Chris Kraus, described as “a horrible storefront in the armpit of Glendale Boulevard and Alvarado Street. There was a Home Depot portable shower, a hot plate, and a toaster oven. That’s all she could afford.”

Twenty years earlier, Becker had the kind of career that artists dream of. Straight out of grad school at 24 years old, her 1996 CalArts MFA thesis project, Researchers, Residents, A Place to Rest, was curated into the São Paulo Biennial, then exhibited at the Kunsthalle Zurich and gifted to MoMA. But by the 2010s, “the combination of addiction, mental illness, and poverty—a killer trifecta,” as Kraus puts it, “had pretty much blown up her career.” She’d given up on making the large-scale installations she was known for. The only thing she had the resources to do anymore was draw. She was literally making these drawings—among them, watering—“to buy food and pay rent.”

I can’t tell you the number of times I saw millennials post Becker’s words: “I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent. I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent. I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent.” It felt like the cry of my generation.

“I could not afford to move to LA now,” says Kraus, who arrived in the ’90s from New York. A longtime resident of the MacArthur Park area, she’s witnessed gentrification sweep Echo Park, Highland Park, and Pasadena. “Now people are moving to San Pedro and Long Beach,” she adds.

Long Beach is where I watched the artist Pippa Garner die. She’d once lived in the Los Altos Apartments & Bungalows on Wilshire Boulevard, an Old Hollywood landmark turned bohemian enclave, where, up until the early 2010s—as I was told by the artist and astrologer Margaret Haines—you could still find a deal as an artist if the super liked you. Haines took me to the Los Altos in 2017, hoping to secure me an apartment, unaware that management had changed. We toured the Marion Davies suite: pink, gold, and now $6,000 a month. A year later, LA—the serendipity capital of the world—brought me to Garner’s door. We became so close that calling her Garner feels wrong. Pippa was broke. She was a trans artist who bucked convention for fun, but she didn’t choose Long Beach for fun: It was affordable, safe for queer people, and close to a veterans hospital where she, a vet, could receive free care. She had cancer. Pippa’s people were in LA proper; the isolation made her twitchy.

The year I met Pippa, 2018, Defend Boyle Heights, an “anti-gentrification” protest group, targeted art galleries around the predominantly Latinx LA neighborhood to fight the displacement of longtime residents. I was assigned to interview photographer Catherine Opie and asked her if she felt responsible for gentrification as an artist. Sometimes called the “mayor of Los Angeles” due to her civic engagement, Opie knew about the protests. “I don’t feel responsible,” she replied. “Artists seek space that they can afford, and then other things follow.”

I agree with Opie that artists shouldn’t be scapegoats for a system that sees their value and exploits it. Although, by now, the racism and classism that fast-track gentrification, and the instrumentalization of white artists in that process, have become so obvious that it’s important to be mindful of where you move as an artist, in the same way housing activists should pick their targets wisely. What I remember most from the Defend Boyle Heights moment was anger: anger that some people might lose their jobs and others, their homes. Anger that city-level or nationwide housing reform seemed impossible. Anger that dialogue was so strangled.

Where do we put our anger? Defend Boyle Heights resulted in the closure of a few galleries. Kraus was attacked for her affiliation with one of them and for writing about her small-time real estate business, something she continues to do in her latest novel, The Four Spent the Day Together, which, after being released in October, provided fodder for debate on how artists make home in Trump’s America.

This has been the year of fire and ICE in LA. Over 16,000 homes and structures were destroyed in last January’s wildfires. Months later, people set fire to police cars and Waymos to protest ICE’s violent raids on supposedly undocumented immigrants; people were arrested, deported, disappeared. Haines says LA is undergoing its “Pluto Return,” an every-250-year occurrence she describes as “a deep car wash of alchemical change and revolution through brutal destruction and sweep.” After a period of “nauseating whiplash,” the city should find “strength, ascension, and absolution” by 2028. “It really is the Phoenix rising.”

Tracy Rosenthal and Leonardo Vilchis, co-founders of the LA Tenants Union, seem to harness a similar hope in their 2024 book, Abolish Rent: How Tenants Can End the Housing Crisis. “In Los Angeles alone,” they write, “600,000 [tenants] spent fully 90 percent of what they earn keeping a roof over their heads.” That’s just one statistic they cite regarding how dire things have become. In Abolish Rent, LA—a city on the vanguard of class war and climate crisis—becomes a canary in the coal mine for the rest of the nation. But, they suggest, it might also offer a vision for a more equitable future that could be achieved through tenant organizing. Canaries rising?

In resistance to the prevailing belief that you must live in an art capital to be an artist, these four off-center setups promise even more heretical possibilities.

-

BRING THE ART WORLD TO YOU. That’s what artist manuel arturo abreu and alternative educator Victoria Anne Reis have done with their ongoing program, home school. Launched out of a shed in the back of a punk house in Portland, Oregon, where abreu lived for $300 a month, home school “emerged as a way for us to DIY a space for critical engagement with contemporary art, specifically with a distance-learning, remote, online focus,” they explain. The organization has featured talks and performances with artists from all over the world, including Hamishi Farah, Eunsong Kim, Kearra Amaya Gopee, and Jasmine Nyende. “We describe it as a free pop-up art school and space of sacred duty. At this point, it’s kind of a Portland classic.”

-

TURN A RURAL RENTAL INTO A PRODUCTION STUDIO. In early 2022, actor Callie Hernandez (of La La Land and Alien: Covenant) began getting a bad feeling about her industry. Her dad had just died, and she felt “bored in Los Angeles and bored of the ways the studio system worked—or didn’t work.” Then the dancer Brittany Bailey, a collaborator of dance legend Yvonne Rainer, asked the actor if she’d be willing to split a rental in the Berkshires. “I said, ‘Yeah, if I can make movies.’” During the big Hollywood strikes of 2023, Hernandez self-funded four: a “Curb Your Enthusiasm-type experimental film” featuring Andrea P. Nguyen; a collaboration with director Pete Ohs and actor-writer Jeremy O. Harris called The True Beauty of Being Bitten by a Tick; artist Olivia Erlanger’s short film Appliance; and Invention, an auto-fictional biopic about Hernandez’s health guru and inventor father that’s one of the best American indies I’ve seen in years.

-

FOUND A COLLECTIVE DREAM HOME. Artists and free thinkers love to say that they want to “leave the city and start a commune.” But how is that done exactly? The New York-based media collective PIN-UP offers some clues in their 2024 film Dream Homes. Commissioned as part of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s 2024–25 “Making Home” triennial, Dream Home spotlights three LGBTQ+ living cooperatives across America. The rural ones are more cloistered, self-sustaining bubbles, while the third, House of GG, founded by the late Miss Major, a Black trans activist who participated in Stonewall, is strategically placed in suburban Little Rock, Arkansas, to affirm local trans women of color.

4. BUILD AN ART TOURISM DESTINATION. Prior to moving to rural Athens, Ohio, artists Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch lived in New Orleans, Oberlin, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles—cities where they’d find affordable rentals and build what Fitch calls “these big, crazy sets.” Their friends would fly or bus in to participate in Fitch’s and Trecartin’s work—filming them speaking Alice in Wonderland-style poetry directly into the camera at 2.5x speed, hosting hype houses before Hype House, capturing the mania of social media that was still to come, and establishing themselves among the most influential, prescient artists of the millennial generation.

“Movie making is expensive,” Trecartin says. “You break even if you’re lucky.” In 2019, Fondazione Prada commissioned an exhibition from the pair. The artists’ “wildest idea” for a show was to purchase rural land in their home state for the sets, including a lazy-river-style water park, and film there. Eight years later, the Athens property continues to serve as Fitch and Trecartin’s primary residence. Ultimately, they hope to build out a park with featured rides by fellow artists, and maybe eventually “hand it over entirely” to the public. “Like Spiral Jetty,” I suggest, and they both laugh, repeating, “Uh-huh. Exactly.”

We’re nearing the end of our descent. Are you exhausted? Welcome to burnout.

Burnout can take place anywhere; it’s the slow erosion of our souls inside our first home—the body. Rampant across many fields, and especially among care workers, burnout is noticeably impacting artists, whose job is to exhibit spirit. “Thin, rushed, and confused,” is how one curator I spoke to, who prefers to remain anonymous, describes much of the art being made now. Rather than blame “politics” for today’s lackluster art—as my former roommate, Dean Kissick, who used to sleepwalk naked, proposed in his viral Harper’s cover story “The Painted Protest: How Politics Destroyed Contemporary Art”—this curator suggested that artists are being forced to rubbed damp sticks together. They’re trying to do too much, too fast, with too little in the recent aftermath of a moment where amassing capital from art seemed more accessible than ever—and certainly for more types of people.

Being a career artist used to be the prerogative of the leisure class and resolute white men, demographics far less likely to accept shitty working conditions or engage in activism, and far more likely to have wives and staff to tend to them. Now, brilliant artists like Jade Kuriki Olivo, a trans woman of Japanese and Puerto Rican descent, grace magazine covers and exhibit worldwide. In recent years, Olivo has turned her practice over to activist concerns, hosting free HIV testing, memorials for “unalived” trans individuals, and fellow trans activists inside of her shows. For her 2023–24 exhibition titled “Nothing New,” Olivo wanted to live out of the New Museum, “in this glass aquarium 24/7.” She would recreate her bedroom, contrasting its sanctuary-like qualities with the public scrutiny that trans women experience daily, represented by the museumgoer’s gaze. Had the proposal been approved, Olivo would’ve managed to sublet her actual room and save the exhibition honorarium. Instead, she had to clock in and out, taking on additional work outside museum hours to cover her expenses. At one point, she contracted Covid and couldn’t work either gig, neither of which offered health insurance or sick days.

“So many artists come here completely depleted,” says Katharina McCarty of her restorative residency, Eighth House. “I worry about them.” McCarty has transformed Quarry Hill, the “radical, hippie commune” she grew up on in Vermont, into a “non-transactional” artist residency. “It’s about gifting a reprieve,” she explains, “from the oppression of high rents and having to work so hard to survive”—struggles that she, the former director of a now-closed gallery, witnessed during her own art-world tenure.

When I knew Kissick, he wanted to be a novelist, but to do so would’ve put him in the vulnerable position of “artist”—having to make something innovative or beautiful or true in advance, out of his own pocket, then try to sell it, a gamble. As if making art isn’t hard enough, the current system—in the U.S., at least—puts the onus completely on the artist until they’ve proven themselves to be a market force. It’s no wonder that so many artists end up addicts, or homeless, or pandering, or dead—fates storied in Hari Kunzru and Hannah Regel’s recent artist burnout novels, Blue Ruin and The Lane Sane Women.

In Dante’s Eighth Circle of Hell, frauds are punished according to their specific misdeeds. Flatterers wrestle in shit. Thieves are eaten by reptiles. Panderers are whipped by horned demons. Corrupt politicians boil in tar. Sowers of discord get their bodies torn apart. Fraud thrives in creative industries. In the eighth circle, we put the inaccessible homes of wealthy collectors who only collect sure things in competition with their rich friends. We could also put whatever you call someone who isn’t really an artist but who cannily games the system here. “Artist” is a great profession if you can hack it, and hacks often can. They go on to buy condos while many true artists, too sensitive to play the game, die with a life’s work in their rented real estate, like Vivian Maier and Henry Darger (this almost happened with Pippa Garner; a few curators intervened at the 11th hour).

In the eighth circle, we could also put career artists who situate their studios somewhere “cheap,” using their surplus income to fly to art fairs, fashion weeks, and biennials. Thailand, Portugal, Georgia, and Mexico are some of the “affordable” countries where I’ve known internationally renowned artists to live and work. I don’t think this is a sin, necessarily. It can be done respectfully, especially if the artist has ancestral ties to the place. I am thinking of this one example, though, of a contemporary artist who worked out of my Canadian hometown, a city that used to be very affordable and is somewhat less so now. This artist was called out and half-cancelled for #MeToo transgressions. Curious about the case, I talked to locals. There were more complaints about this artist’s labor practices than his sexual proclivities. Young people who had worked in his studio felt undercompensated, overworked (weird hours), and like their ideas and personal lives had been mined for content. People stayed because this studio was the only place in this second city where an aspiring artist could cut their teeth. Was it fraudulent to exploit this? Maybe. I’m more concerned about the fraudulence of a sex scandal headline when the true grievance had to do with labor practices. But labor’s boring, right?

Congratulations, you’ve made it to the deepest ring of this American hell: Florida.

After the global Covid-19 lockdowns, Naomi Fisher returned to her hometown of Miami, Florida, only to discover that rents had more than doubled. Fisher is one half of Bas Fisher Invitational (artist Hernan Bas is her counterpart), a nonprofit that has connected Miami’s art scene with the international one for two decades. Bas Fisher got its start when, in 2004, the two artists became the beneficiaries of real estate developer and collector Craig Robins’s rejuvenation of the Miami Design District. Robins, a student of SoHo developer Tony Goldman, invited artists to activate empty upstairs spaces in commercial buildings he’d acquired at generously subsidized rates. He is known for preserving Miami Beach’s Art Deco historic district through similar means. Fisher and Bas turned part of their massive studio into an exhibition space for their peers. “At that point,” Fisher recalls, “Miami was so inexpensive compared to the rest of the country. I felt it was so undervalued, magical, and wonderful.” Art Basel Miami Beach had launched two years prior, and an art-development boom had begun.

Now, Robins has partnered with LVMH and Miami’s Design District is a luxury destination where you can shop every high-end brand from Brunello Cucinelli to Versace, stop by Christie’s auction house and Avant Gallery, and run into public art by Jill Mulleady, John Baldessari, and Zaha Hadid. The neighboring Wynwood Walls, Little Haiti, Overtown, Little River, and Allapattah are all being developed by various collectors and firms as arts destinations with galleries, studio spaces, and public and private art institutions. After their sponsored lease ended, Bas Fisher fell in with another real estate business, ultimately deciding to go “fully nomadic in direct response to being gentrified out of every place that we’ve been.”

Are artists complicit in their own displacement? Sharon Zukin’s touchstone study of artist housing and gentrification, Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change, celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2014 with a new edition that emphasized that many of the artists who pioneered the practice have since been priced out of the market. “It’s wild,” Fisher admitted, “that in my hometown, my organization—basically a mini arts tourism bureau highlighting how incredible artists from Miami were—helped create a situation where a lot of those people have left or are struggling to stay.”

When it comes to affordable housing justice, we’re collectively stuck between a rock and hard place—the rock being leadership and landlords who benefit from the current system, the hard place being burnout from a calling that relies on emotional labor and, frequently, a rejection of social norms. Too many artists—and people in general—are working too hard to afford rent as it is. Who’s got the energy to organize? The LA Tenants Union’s Rosenthal and Vilchis would have you start small. They’d also like to see the term “housing crisis” thrown out. “Framing the consequences of our housing system as a ‘housing crisis,’” they write, “ignores that from the perspective of its winners, the system works just fine… Housing isn’t in crisis, tenants are.” Kraus calls out “the culture of silence around money and wealth” as another factor.

There are many reasons why people in the arts aren’t forthcoming about issues like housing. Artists who are struggling might not want to admit they need help because they depend on an image of success to get paid at all. Those who benefit from the current system tend to enjoy that in silence, or choose silence for fear of being called out or cancelled if they’re honest. This leads to mystification and isolation. If you don’t know how the system works, how can you change it? It’s not easy to get people to speak candidly about these things. The voices in this article represent a minority.

Order your copy of CULTURED at Home for more stories like this one here.

in your life?

in your life?