A Rare Peek Inside Coolwater, the Storied Connecticut Compound That’s Captivated Generations of Designers and Architects

Every house tells a story of its inhabitants, but very few tell the stories of generations. Coolwater belongs to the Childs family, who have lived in Norfolk, Connecticut for more than a century, and still do.

The estate was originally a colonial farmhouse built around 1803 by the Tibble family, who farmed the surrounding land, and was purchased by the Childses in 1909 from Ralph C. Burr, a descendant of Aaron Burr. It possesses the typical features of a colonial home: an inviting hearth, wide maple and pine wood floorboards, perilously steep stairs, low ceilings, and terrible insulation.

Over more than a century in the family’s care, it became a grand house capable of sleeping hordes of guests and a robust live-in staff. There are delightful nooks and hidden crannies throughout—Star Childs, one of the family’s elders, recalls an attic-dwelling uncle known for hiding his brandy in the wood-paneled walls. In 1930, the elder Childs commissioned a monumental Sport House from Taylor, replete with a fives court, a basketball court, and a gun room. Its sloped roof was designed to appear sagging with age as slate shingles laid using forced perspective produced an air of grandeur. Summer plays were staged under the dramatic glow of the wooden turret’s stained-glass windows…

Eiesha Bharti Pasricha Has Given Her Fictional Muse a Maison, a Manor, and Now a Fashion Line

Just an hour and a half outside the city, Estelle Manor—108-room hotel and members’ club—occupies the former Eynsham Hall estate in Oxfordshire. A mix of Edwardian bones and bold contemporary touches, the manor—jaw-dropping in its old English grandeur—opened in 2023 as a rural escape, complete with four restaurants, a Roman-style bathhouse, and rolling parkland. Creative entrepreneur Eiesha Bharti Pasricha describes herself as its “co–creative director,” along with her husband…

What Do You Get When You Cross Traditional Japanese Architecture with American Materials?

Johnston Marklee’s Canal House sits on one of Kyoto’s centuries-old cherry-tree-lined canals. Completed in 2021, it embodies the fluid convergence of American and Japanese architectural traditions: where neighboring homes are made with a reverence for wood, the Canal House is built from concrete. Single Yoshino-style windows float below its terraced eaves like moons, each tier buttressed by concrete struts instead of traditional bamboo ones.

Inside, the house revels in itself: each level looks onto a glass-enclosed inner courtyard studded with mossy rocks, while cantilever staircases offer a glimpse at above from below. The house’s street level holds both a two-car garage and a Sukiya-style, wood-panelled tea room…

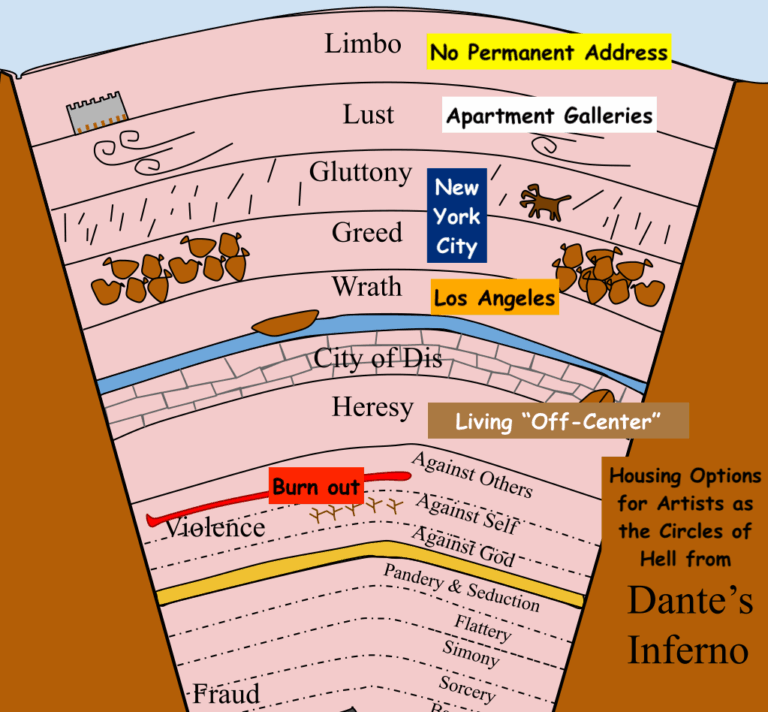

See Inside the Loft of Designer Stella Ishii, a Relic From a Time When Artists Ruled SoHo

New York’s city government passed the Loft Law in 1982, bestowing legal occupancy and stabilized rents on artists who had laid claim to the city’s abandoned industrial buildings in the 1960s and ’70s. The following years galvanized SoHo as an incubator for figures (among them Gordon Matta-Clark—who later opened his artist-run restaurant FOOD on Prince and Wooster—Donald Judd, Joan Jonas, gallerist Paula Cooper, and choreographer Lucinda Childs) whose work would come to shape the next 50 years of American art, literature, criticism, and fashion.

Stella Ishii is part of this lineage. Before she was co-owner of cult fashion showroom the NEWS or founder of her label 6397, Ishii was making regular pilgrimages from her native Japan to the U.S. at the right hand of Comme des Garçons founder Rei Kawakubo. She settled in SoHo just as the promise of loft living was constricting around its forebears and, with her artist husband Jerry Kamitaki in 1997, managed to buy one of precious few such properties—a 3,000-square-foot space in one of the neighborhood’s historic cast-iron buildings—still available at an artist’s price point. The space has been a willing co-conspirator for Ishii’s creative musings ever since: a backdrop for performances, a guesthouse for visiting artists, and a plinth for displaying her various forays into collecting (see her sugar wall and illustrious remote collection)…

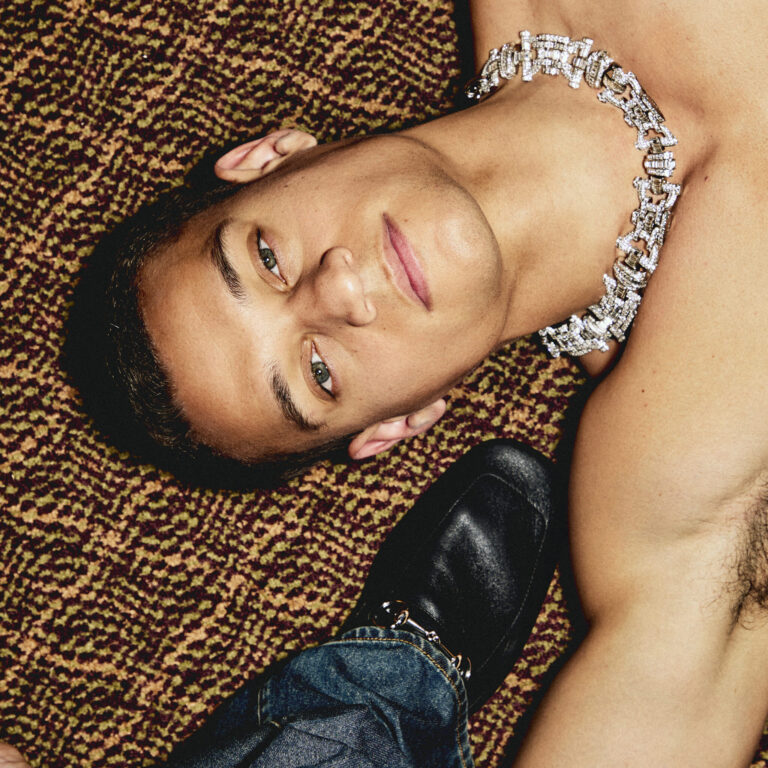

Opera Singer Anthony Roth Costanzo Lives in a Gem of Queer Architectural History. It Requires Some Compromise.

Just blocks from the Chelsea Hotel sits a remarkable piece of New York architectural history: the former home and office of architect David Webster and his partner, the writer and AIDS activist Larry Kramer. Completed in 1981, the preserved interior is a rare surviving example of High-Tech design, an off-the-shelf, ad-hoc, and industrial approach to space-making that emerged in the late 1970s.

Today, the home enters a new chapter, having been recently purchased by countertenor phenom and general director and president of Opera Philadelphia Anthony Roth Costanzo, who is carrying forward—with the very hands-on guidance of its creator and former tenant—the character of the design and the spirit it represents…

Look Inside the Art-Filled Montauk Home of New York Design Staples Stephen Alesch and Robin Standefer

On the edge of the 99-acre Shadmoor State Park in Montauk, Sea Ranch is spread over three modest mid-century structures, set amid a wild wonderland of mature trees, indigenous flowers, and medicinal plants. The result: a sliver of French countryside meets Scandinavian-SoCal bohemia, elements of which wind through some of Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch’s most high-profile projects as cofounders of the ne plus ultra architecture and design studio Roman and Williams.

The couple’s hybrid home-workshop has become the laboratory for everything they do. It’s where Alesch makes furniture prototypes and Standefer, a New York native, experiments with assemblage and ceramics. “These things just wouldn’t happen in the city because of the intensity there,” she says. Alesch adds, “We never have a conversation about the cost of things or margins in Montauk. That’s city talk…”

Artist David Salle Takes Us Inside His Hamptons Home, and Reveals How He Chose the Pieces on Its Walls

There are Hamptons artists, and then there is David Salle. The renowned Neo-Expressionist’s presence on the East End affirms the region’s place on today’s art history map, much like the titans of Abstract Expressionism did in the last century. For 40-plus years, Salle has been known for richly collaged mash-ups of high-low imagery that interweave pop culture references, cartoons, interior decor, print media, television iconography, and art masterpieces to capture the essence of Postmodernism and the contemporary.

For decades, Salle has split his studio time between New York and the South Fork, where he lives in a cluster of 18th- and 19th-century barns…

Look Inside Art Advisor Rob Teeters’s Sagaponack Home, Where Third-Century Sculptures Coexist With Conceptual Greats

Rob Teeters, the art advisor who founded Front Desk Apparatus in 2006 and leads the Dallas nonprofit art space the Power Station, shares his 1950s Sagaponack home with his husband, ceramicist Bruce M. Sherman. The latter’s latest polychrome pieces punctuate their shared collection with a winking energy and warmth throughout the modern glass-and-wood-led space. In the dining room, a third-century Roman marble head stands sentinel, while a Courbet portrait beckons down the hall; elsewhere, contemporary works by Wade Guyton and Sherrie Levine balance the craft practices on view with a more conceptual bent. Teeters approaches each arrangement with the keen eye of someone who does this for a living—though, with no clients to please here, he’s given himself free rein…

in your life?

in your life?