For her current show, “Bíikkua (The Hide Scraper),” at Los Angeles’s Roberts Projects, Wendy Red Star stepped back from the humor that often carries through her work. Instead she dug into the Apsáalooke history of bishkisché, traditional leather pouches, to share a little-documented history of her people. Bishkisché were functional objects used to transport goods through the Great Plains. They were also creative expressions, meticulously designed and painted by Apsáalooke women and passed down through generations as keepsakes.

Through extensive research, Red Star uncovered more than one thousand bishkisché, using the designs to create her own works through an intensive painting process. Of more than 200 that she created, 184 are now on view through Aug. 24. Hung in groups of four, the complexity of each is complemented by its surrounding selection. Also on view are 12 historic editions from Red Star’s personal collection.

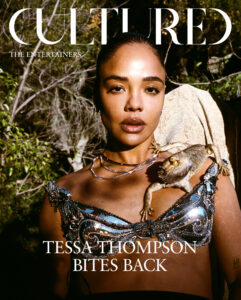

Red Star checked in with CULTURED to share what moved her most in creating these works, the significance of the titles, and how they relate to her recently installed piece, The Soil You See…, at Tippet Rise.

CULTURED: Your current show at Roberts Projects explores the aesthetic history of bishkisché, small leather pouches used by indigenous groups to transport goods. In the Apsáalooke and Plateau indigenous traditions, women would decorate these pouches with geometric designs—making them both functional and expressive. How did you come to study these objects?

Wendy Red Star: My journey into studying bishkisché began with a deep interest in understanding and reclaiming Apsáalooke women’s artistry. These leather cases, painted with intricate geometric designs, hold layers of cultural significance that go beyond their functional use. Researching them was like opening a window into the past, allowing me to connect with the creative practices of my ancestors and bring that history into contemporary discourse.

CULTURED: What are some of the aesthetic qualities you would use to describe these objects?

Red Star: Bishkisché are powerful in their simplicity and elegance. They feature bold geometric patterns, in strong, contrasting colors. These designs are not just abstract geometric designs; they convey a sense of identity and belonging to specific communities. The craftsmanship shows a keen attention to balance, symmetry, and rhythm—each representing the tribal aesthetic through its form and design and colors.

CULTURED: How were they contextualized by the women who made them. Would they have treated them as “art,” or how would they be cared for, handled?

Red Star: For the women who made these cases, they were not merely utilitarian objects, but expressions of personal and cultural identity. While they may not have considered them “art” in the way the term is used today, they certainly valued them as embodiments of skill, tradition, beauty, and community representation. These cases were cherished, and passed down through generations, making them treasured family heirlooms.

CULTURED: This show required significant research of specific objects and people. What were some of the unexpected discoveries?

Red Star: One of the most unexpected and profound discoveries was the sheer diversity of designs and techniques used by Apsáalooke women across different periods. It revealed to me a dynamic artistic tradition that was continually evolving. Another discovery was the stories behind some of the cases, which spoke to the resilience and creativity of the women who made them.

CULTURED: Your work has always been multidimensional and multimedia, but this show extends that further with the intensive painting process you used to make the work. How did this process evolve?

Red Star: The intensive painting process for this show evolved from my desire to fully immerse myself in the creative techniques of my ancestors while also pushing the boundaries of my own practice. Each piece involved multiple layers, from drawing to painting to cutting and assembling, echoing the meticulous craftsmanship of the original cases. This method allowed me to create works that are both historically rooted and innovatively contemporary.

CULTURED: Each of the works is named for an Apsáalooke woman whose name you found in a 19th-century census. Can you describe the experience of uncovering these names? Were you able to uncover additional details about any of these women?

Red Star: Uncovering the names from the 19th-century census was a powerful experience. Each name is a fragment of a life, a story, a legacy that deserves to be remembered. While the census didn’t always provide detailed information, the act of naming these works after Apsáalooke women is a way of honoring their memory and giving them a presence in the present.

CULTURED: This summer also saw your sculpture The Soil You See… installed at Tippet Rise in Montana. What is the relationship between the works at Roberts Projects and the sculpture?

Red Star: There’s a deep connection between the works at Roberts Projects and my sculpture, The Soil You See…, at Tippet Rise. Both are grounded in Apsáalooke culture and explore themes of identity, land, and heritage. While the Roberts Projects show delves into the intimate and personal through bishkisché, the sculpture expands these themes into the landscape, creating a dialogue between the past and present in both intimate and monumental forms.

CULTURED: How does it feel to have this work installed in your home state?

Red Star: Having The Soil You See… installed in Montana, in Crow country, feels incredibly significant. It’s like bringing my work full circle, grounding it in the land that has shaped so much of my identity. It’s a profound honor to have my art become a part of that landscape, contributing to the cultural and artistic narrative of my community.

in your life?

in your life?