Garrett Hongo and Robin Coste Lewis both attended the same high school in Gardena, California. The two poets are 10 years apart in age, and only met years later—but their respective practices share a preoccupation with that landscape and the migratory geographies that inform it. Lewis’s family can be traced back to Louisiana and moved west during the Second Great Migration. Hongo was born in Hawai’i to Japanese American parents and moved to California as a child. Lewis broke onto the poetry scene with her first collection of poems, Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems, which won a National Book Award in 2015. She only began writing poetry in her late 30s, after an accident left her with a traumatic brain injury. Hongo started publishing his poems in the early 1980s; by 1989, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

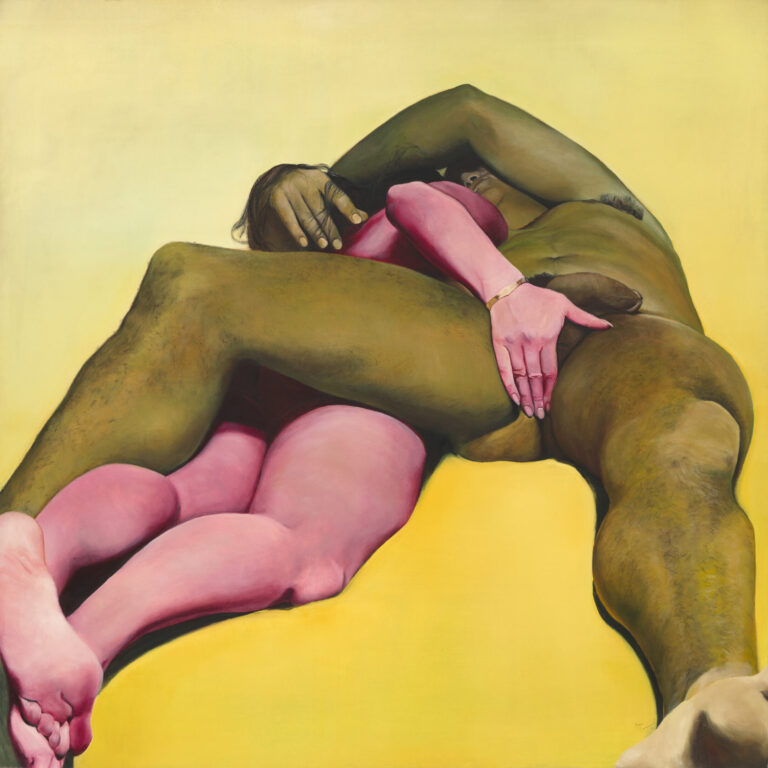

Last year, the two writers came out with books that complicate their relationship to poetry as a form. Garrett Hongo published The Perfect Sound, a wandering and probing memoir of the author’s quest for sonic satisfaction and understanding of identity. Robin Coste Lewis released To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness last winter—a haunting container of poetic slivers and family photographs the writer unearthed over two decades ago. In both works, Lewis and Hongo keep time, hold space, and leave traces, obliterating any expectations for their practice to fit into tidy boxes. To close out National Poetry Month, CULTURED brought the two poets—and close friends—together for a conversation about indulgent hobbies, Easter eggs, and being suspicious of the ego.

Robin Coste Lewis: I knew about Garrett for years and years before I met him. He's a giant amongst us poets. And by poets, I mean poets around the world, but there is a subculture of writers who are from California and Southern California, for whom Garrett is a god. Or pan-Asian writers, from Japanese, Hawaiian, Pacific Rim cultures, who revere him very much.

Garrett Hongo: And I started hearing about Robin from friends at New York University when she was a grad student there. Yusef Komunyakaa said there was this sister who knew Sanskrit. He said, “She's going to be something.” … The next thing I know, she comes out with Voyage of the Sable Venus in 2015, this astonishing book which nobody could touch, man. It was like, from outer space … I was finally able to work it out so I could invite [Robin] to the University of Oregon, and we had a good time because there were so many crossings and commonalities. I only found out about the travail that [she] had to come through after the book was out, which makes it even more remarkable.

Lewis: You know, before my accident, I was a theory head, a fiction writer, a Sanskritist. And then I woke up a poet. I remember telling a friend of mine, who's a deeply experimental fiction writer, “I really like writing sonnets, can you believe that?” [Laughs.] He was like, “Have you lost your mind?” I never looked back. I think my accident was a gift because I don't know that I would have ever started writing poetry.

Hongo: The Buddhist thing is like, Every misfortune is an opportunity. I never believed that shit, but they say it.

Lewis: Did you grow up very religiously?

Hongo: “Areligiously,” American style. My maternal grandfather, Kubota, was a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist. He prayed every morning, so I witnessed it as a child. He had such a bearing of dignity compared to the rest of my family. When I was in college, I started studying Japanese and Chinese literature and Eastern religion and Buddhism. I was also interested in the poetry of Gary Snyder and his involvement with Buddhism. I met Gary when I was very young, and he offered to write me a letter of introduction. And he did, to two things: to Cid Corman, the editor of Origin magazine, and to Shōkoku-ji, the temple in Kyoto. I weaseled my way into a temple in Kyoto for eight or nine months.

Lewis: Did you practice for the whole time?

Hongo: I was a desultory practitioner, let’s put it that way. I was the American, and I was given more license. I didn't realize there would be no girls. I would slip out on weekends and go dancing, and I’d stay out past midnight so I had to climb the wall and sneak through the temple grounds and all that.

Lewis: Oh my god, Garrett, your life! Can you talk a bit about your new book, The Perfect Sound?

Hongo: Well, it's about my very indulgent hobby of stereo audio equipment. It started when I went to La Scala in Milan in 2005, and I heard opera as it should be for the first time … I wanted to know a bit more about the art. I said, I can't come back to La Scala every week, so I better build a stereo system that can play this shit. I found out that most regular stereos could not do it because the difficulty of reproducing those kinds of voices was astronomical for electronic equipment. I wanted an amplifier that was very special, a Japanese one that was built on a throwback circuit, but it was like $9,000. I didn’t have $9,000.

So I was in Hawai'i, and somebody said, “Why don’t you write a book about it?” I immediately called my agent up. She went, “That’s not sexy.” So I said, “What if I write about opera and stereo?” And she said, “How much do you want? Be realistic.” I said, “I need about $9,000 to get this amplifier.” And she said, “How about $75,000?” I got [the amplifier], and I blew it up. Flash of light, like a little Hiroshima. I got it fixed, and then it worked great and I could hear my opera—Renée Fleming, Angela Gheorghiu, Luciano Pavarotti… I was in heaven. So then I had to write the book, right?

It’s a big book about a very small subject, ostensibly. And it is an autobiography of sorts … I write about meeting my best friend in poetry, Edward Hirsch. I talk about singing doo-wop as a junior high school kid, and encountering Joni Mitchell through my first girlfriend. I didn’t know what the hell that was, White girl music, what is this shit?

Lewis: With my first girlfriend, we used to go to Hermosa Beach and she would read poetry out loud to me, and that's how I really became aware of contemporary poetry … It's interesting listening to you talk about sound because it’s such a huge part of our work. I think that a lot of people aren't aware of how closely poets attend to sound.

Hongo: I'm looking through [your new book, To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness,] like it’s our family album. I recognize houses in [these pictures].

Lewis: A lot of people respond to those photographs nostalgically because of their family albums. But people who are from Southern California look at this book and go, “Oh, shit.” That moment in LA architectural history, those palm trees, the Hollywood Hills in the background, they’re little Easter eggs. The book is an homage to New Orleans, to LA, to diaspora as a verb … The role that photography plays in diaspora, migration, survival—not just for Black people.

Normally, people of color have to identify with a protagonist in the story and go, Oh, you know, even though the hero was a white man, it could be me too. We've been asked to do that for millennia. And one of the things that I hope this book invites people to do is to consider that they too can be the protagonists in these images. It's fascinating to see who can make that leap and go “Oh, I'm that Black grandmother.”

Hongo: The way [the book is] laid out, with its mostly black pages and accompanying texts, it creates incredible space that you can re-occupy. The texts are not captions. They’re poetic, yet they're not poems, which demand so much focus of energy and concentration.

Lewis: I have had the photographs for 25 years, and all I knew was that I wasn't mature enough to even think about touching them and that if I tried to write about who the people were in the photographs, I would fuck it up. I don’t know if it’s about America… I deeply suspect that that’s what it is. As artists in this country, we are not taught that enchantment, or wonder, or not knowing, is a valuable aesthetic. We're not taught to be comfortable without standing on a floor, that to be floorless is a valuable aesthetic.

Captions are agents of colonialism as far as I'm concerned. So to play with the reader's indoctrination by captions—“Here is a photograph, here is a savage”—and then not to deliver with information about the photograph, but to withhold information, felt really right to me… Having been made to kneel in the corner and then spanked with a ruler—all the things we did in terms of how colonial our curriculum was—to finally reach a point where I could say to myself that I can put one word on the page and be damned, that took 30 years, to reach that aesthetic psychological place as a Black woman, as an American, as an artist.

Hongo: I’m thinking about the line at the end of “An Idea Of Ancestry” by Etheridge Knight: “I have no children / to float in the space between.” You float in the space between … I was trying to explain this book to somebody who hadn't read it. I said, “It's like she’s comping, she's not playing the melody. She’s hitting the note before, or the suspended seventh between.”

Lewis: I don't think it's a coincidence that so many poets are entranced by music. I think that in many ways, we are musicians too, except that the instrument we use is language. I was just talking to some of my students about how we choose different words simply because the music isn't right with the word. You could say, bread, or you could say baguette; you need the right syllables, the right sound, the right consonants.

Hongo: You arrange language so that the word is not just the word, but it's overtones of silence, you dig? It's not only the weight of any word on the page, but the weightlessness of the silences around it. Like Thelonious Monk played the fucking piano, man!

Lewis: Silence is really important to me. And it's also very important to let the reader do the reader’s work. If I say, “Come with me,” as opposed to “Let me tell you,” it's a different experience for everyone involved.

I think one of the things that I brought from [studying] Sanskrit and Buddhism and Hinduism and different traditional African religions, is just this deep suspicion of the ego. Hilton Als has a great line, “The ego: What a racket.” … In a lot of these cultures and systems of thought, the ego is not given the place of honor that it is given in Western art. That’s why in India you’ll often see gods standing on top of rats, monkeys, or demons. The thing the gods are standing on is our ego. We’re not supposed to invest in the ego and go write 20 books from the place of the “I.” It’s like, No, no, no, that part of you has to calm down a bit, baby, before you pick up a pen.

in your life?

in your life?