“Excuse me, hun. Can you tell me where I can find this dress in the store? I need a size eight,” a young White woman asks me.

Let me start with the first thing that came to mind.Here we go again.

Here we go again, being pestered by White women of all ages in the middle of shopping experiences with questions of shoe sizes or blouses in stock or dressing room locations or how much is something because the tag isn’t—Here. We. Go. Again.

The first time this happened I was eighteen years old. I shrugged it off as a simple mistake, partly because the White woman emphatically apologized and partly because benefit of the doubt and me were such close friends. I thought it was a healthy relationship, like the butter substitute for my popcorn. As I had seen and experienced a great deal of racism by then, I thought, “Why not offer it?” I was unaware of the nuances of racism because I’d had been experiencing blatant racial transgressions for most of my life. Losing your flip-flops while being chased off the road by White men in a pick-up truck was a hell of a lot easier to recognize as racism than the subtlety of being mistaken for staff. I’m talking about the kind of if-Purple-Rain-Prince-had-gone-shopping-and-a-White-woman-asked-him-for-a-size-eight mistaken for staff. Who in the heck would’ve mistaken Prince for a retail employee? Exactly. It would have been obvious that Prince didn’t work at the store by his attire alone, and I’m not calling myself Prince by any means but... well... it couldn’t have been more obvious that I wasn’t an employee, by my attire alone.

Unbeknownst to me, I had been experiencing microaggressions from you-speak-so-well and you’re-so-tall-must-play-basketball purveyors of subtle and not-so-subtle racism for most of my life. Whether or not racial microaggressions arise from “good intentions” is beside the point when they are birthed from racial prejudices. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve been mistaken for an employee in stores, but after the fifth or sixth time I kicked coincidence’s ass out and benefit of the doubt and me don’t talk no more. What was once difficult to recognize is no longer such.

Now, this is not to say that being confused for an employee is an issue only Black people face; however, the alarming reoccurrences towards those who are clearly not employees (being mistaken for an employee in a store where employees wear uniforms) or the refusal to believe one’s occupation (customers expressing disbelief that said person is a doctor or nurse or lawyer) are particular to Black and brown people, as these incidents arise from either conscious or subconscious prejudices. Imagine a Black patron shopping in a shoe store while wearing her military uniform, adjacent to employees dressed in all-black uniforms, being asked to retrieve a size six shoe by a White patron. Did I mention the Black patron is wearing a whole entire military uniform and that this is a true story? With all this in mind, are the culprits aware that their confusion saddles comfortably atop of racial prejudices and biases? No. Does that unawareness, regardless of intentions, excuse their confusion as merely an innocuous mistake? No.

It is imperative to point out that the issue wasn’t that I was offended at being confused for a retail sales employee because of the occupation. The issue is that Black people are never “confused” for or believed to be anything other than retail or domestic workers. Why aren’t Black people confused for a doctor or a scientist or a lawyer and so forth? Why does the extent of this White “confusion” cease at retail and domestic work, or jobs swirling around entertainment and sports?

Tamika Cross, a Black physician, was turned away by an attendant on a Delta flight when she offered help to an unconscious passenger who needed medical assistance because no one believed she was a physician. The flight attendant told her, “‘Oh no sweetie, put your hand down, we are looking for actual physicians or nurses or some type of medical personnel; we don’t have time to talk to you.” Her story went viral. Shortly thereafter, The Washington Post did an article and was flooded with emails from Black nurses, doctors and pharmacists who shared similar accounts. During his commencement speech at Harvard University this spring, the inimitable Bryan Stevenson, a lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, recounted one of his first cases. The White judge, assuming he was a defendant because of his race, instructed that he should not be in the courtroom until his lawyer arrived.

What was at the root of this phenomenon? Was their incapacity to see Black shoppers as fellow consumers exacerbated by their limited interactions with Black people in a myriad of occupations outside of the ones that did not immediately aid them? As I look at this young White woman, who impatiently awaits my response regarding the size eight, the sudden urge to commence the mother of all eye rolls is overwhelming. I endeavor to eye-roll this White woman back to the 1950s. However, since racism is alive, well and thriving in 2020, my eye roll didn’t have to work too hard. I worked in a department store as a teenager and as much as I utterly adored waiting on a barrage of testy women yelling their shoe or dress sizes at me (I conveniently lacked a significant amount of effort in finding their sizes in the back storage room), I do not miss those days. A stampede of elephants being chased by a pride of lions followed by a cackle of hyenas seemed vastly less intimidating than a herd of women shoppers on discount days. It was an arduous and demanding job that dealt with numerous difficult temperaments and I had left those days behind me, or so I thought. However, not even wearing a hat the size of Italy with sunglasses the size of Jesus’s manger and a phone in hand could persuade these White women that I was not on the clock.

Once my mother of all eye rolls had completed its journey, providing plenty of oh-shit-my-mistake-she-isn’t-an-employee-let-me-apologize time, I gave the woman the most saccharine of grins and wielded the most lethal weapons in my arsenal—sarcasm and humor—weapons I’ve deployed for most of my life to combat hardships and the immediate invasion of racism in my midst. Without an iota of vacillation, I replied, “Just go up those escalators, make a right and keep straight until you see a sign that says, ‘All Black People Don’t Work Here.’” Aghast, she sucks in her cheeks and a small whoosh sound escapes. She has no clue how to respond and I can tell by the lack of “Oh, my bad” that she is the one who is offended. Sigh.

Here we go again.

My mom was almost ran off the road when my twin sister and I were babies in the backseat due to racism. Bricks were thrown into our home due to racism. As I mentioned, we were the targets of a hate crime at eleven years old when young White men endeavored to hit us with their pick-up truck while yelling racial epithets, yet no consequences ensued because one of the boys was related to one of the police officers at the precinct. As children, we would witness an unarmed Black man almost lose his life to two state troopers. (Our father, harassed many times by Baltimore County police while driving, testified in court as an eyewitness on behalf of the man attacked.) My twin sister was wrongfully arrested and incarcerated in 2015, then offered a settlement by the NYPD when she filed a lawsuit. In 2016, I was singled out—as the only passenger of color in a Macedonian airport—for a strip search by a male police security officer. I refused to do so until a female officer conducted the search, which afterwards led to my public complaint and the involvement of the US Embassy.

Yeah, I know, a laundry list, but I’ve experienced my fair share of blatant racial transgressions. I’ve also had numerous encounters with its offspring, long before I realized the offspring even existed. Racial microaggressions routinely pop up in my life like robocalls and unwelcome pimples.

“Excuse me, this is the priority line. Economy is over there,” a White woman standing behind me loudly announces. With a head swivel that could rival Linda Blair in The Exorcist I turned to look at this White woman while my body emanated oh-this-brown-skin-don’t-look-like-priority? energy. Aside from not-looking-like-priority-material, I’m apparently illiterate as well. Now I’ve been turned into some non-priority-blind-and-illiterate-Black-woman. She saw my brown skin and assumed I was not First Class. Yeah, yeah, I know, “First Class problems,” but it is a brand of racial microaggression I experienced often with my sister, as our work within the fashion industry resulted in companies flying us First Class.

I’ve also been asked by flight attendants for my ticket, you know, because apparently I’m an illiterate and blind Black woman who can’t read her ticket, so I must be in the wrong section. Were any of the First Class White passengers presumed to be blind and/or illiterate? Nope. Just me. The following lyrics by Mos Def often come to mind:

Like, late night I’m on a first class flight

The only brother in sight

the flight attendant catch fright

I sit down in my seat, 2C

She approach officially talkin’ about, “Excuse me”

Her lips curl up into a tight space

‘Cause she don’t believe that I’m in the right place

Showed her my boarding pass and then she sorta gasped…

“Excuse me, how do I get backstage?” a White woman asks my Black boyfriend with the smell of tequila on her breath, giving those tall inflatable balloons at car dealerships a run for their money as she swayed erratically before us. We’d spotted her inebriated gait thirty seconds ago in the nearly-all-White crowd as she looked around in consternation until eyeing us. She nearly bumped into two White employees dressed in the festival’s employee uniform. In fact, she passed by everyone with the exception of two people. My boyfriend and me. The only Black people in the vicinity. Yup. Here we go again.

Did she not see my leisurely placed limbs wrapped around my fine-ass Black man? Did she not see the gargantuan red cups of libations near our lips? Our mundane pedestrian wear amongst a sea of mundane pedestrian wear? I looked at her and without a scintilla of vacillation calmly responded, “Not all Black people work at the festival. There is an employee five feet behind you who you can ask.” She looks at me in that sun-in-your-eyes blinking sort of way and wails, “Oh my gawd! I’m not racist!”

Ever hear of the photograph of the dress that went viral? The dress’s colors were up for debate because, through some perceptive fluke, some either saw black and blue or white and gold. Well, consider this a subsidiary case, insidious in nature, with racial microaggression written all over it. When looking at the color of our skin, some saw employees and others saw attendees. These racial microaggressions are nothing new.

“You don’t sound Black.”

“You’re so articulate.”

“I didn’t know Black women could grow their hair that long.”

“You’re tall. Do you play basketball?”

My twin sister and I were always two of the tallest girls in our class in grade school through high school. I considered reading and writing as exciting as a field trip to the amusement park. I wasn’t half as insulted by that stereotype as a child as I was by the assumption that writing skills weren’t attributed to tall Black people. My twelve-year-old self thinking, “Wouldn’t it be great to hear, ‘You’re so tall. You must be a writer!’”

“Sounding Black” or “sounding White” are stereotypes that even inundate Black and brown communities (as do backward ideologies revolving around colorism or stereotypes regarding Black women and natural hair, as if a Chupacabra is more realistic than a Black woman growing her own long inches). It’s as if rigid parameters exist for a person sounding Black and anyone who steps outside of those parameters is not deemed Black enough. Even words that are synonymous with Black communities such as “ghetto” and “ratchet” imply that good character and intelligence are lost in the Bermuda Triangle of misconceptions ensconced in racial microaggressions and racial transgressions.

When taxis were a thing in New York, I was often passed by drivers looking for potential White customers. Assumptions that I sell drugs because of my hair and skin color by White male Giuliana-Rancic-Patchouli-Weed acolytes looking to buy marijuana. I-Only-See-White-People baristas or salesclerks ignore that I’m next in line when a White customer is behind me.

How one responds (or doesn’t respond, as no one is obligated to react) to racial microaggressions can be emotionally taxing because of their pervasiveness. As I demonstrated earlier, I’ve learned to combat them with a concoction of sarcasm and humor. Partly because who wants to be angry all the time (although warranted, incessant anger has physical consequences for the body and I’m not about to let anyone get in the way of my Black-don’t-crack magic). Partly to denounce their erroneous assertions and make it clear that, indeed, what they are doing or saying is racist, whether they are aware of it or not. I make these clarifications on behalf of myself, not out of desire for some teachable moment, albeit the mere act of doing so, if it prevents the person from repeating these racial microaggressions, could very well be just that.

Sometimes I’m met with guilt. Sometimes I’m met with astonishment. Sometimes I’m met with anger, as if the very nature of calling out their wrongdoings is an affront to them and not me, which opens up the discussion for deeper conversations about White fragility and privilege. Any discussions about racial microaggressions must lead to bigger discussions about systemic racism. How we speak out when discriminated against, or on behalf of others, is imperative. As author Zora Neale Hurston once wrote, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” What is also imperative is people’s willingness to accept their own culpability in enacting racial microaggressions and stereotypes, while endeavoring to learn and grow rather than taking offense.

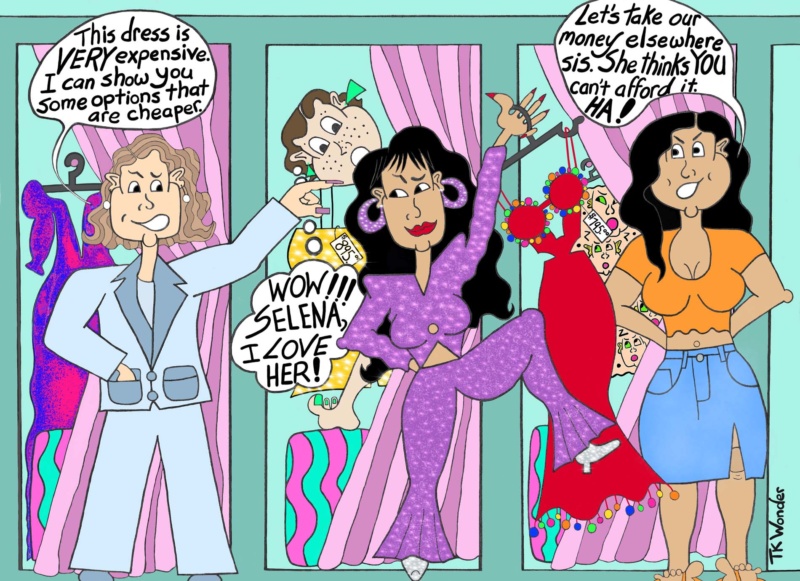

Even fame and wealth do not escape racism’s grasp. Oprah in a shop in Switzerland confronted with a that-bag-is-too-expensive-for-you saleswoman. A perfectly reasonable assertion. The sales rep was only telling a billionaire she couldn’t afford a $38,000 bag. A Sephora employee calling security to make sure SZA wasn’t stealing. Hey, reasonable assertion. SZA has only sold millions of records and made millions of dollars. Danny Glover unable to hail a taxicab time after time when drivers refrained from stopping for him to pick up White customers instead. Totally reasonable assertion. He’s only a lead actor in multiple blockbuster films with a bank account to reflect that. Selena in a high-end boutique, rebuffed by a you-can’t-afford-that saleswoman as she attempted to try on a couture dress. Again, a perfectly reasonable assertion. She only sold millions of records and was looking for a dress to wear to the Grammys.

The fact that their fame and wealth were not recognized is beside the point. Though these are examples of blatant racial transgressions rather than racial microaggressions, the conclusion remains the same. These you-can’t-afford-that or you-must-be-stealing-because-you’re-Black acolytes are everywhere, as reliable in their frequency as seasons of The Simpsons.

The last time I went shopping, I was in a department store contemplating whether a potential buy from a Black designer could accommodate the size of my derrière; however, I was also pondering whether the eradication of racial microaggressions is a possibility? Shopping at Black businesses is certainly an immediate solution for the racially-motivated mistaken identity crisis that is inflicted on Black and brown shoppers, however, it does not resolve the bigger issues. Is the eradication of racial microaggressions truly realistic? No. Could at least an understanding and desire to change subtle iterations of racism lead to viable reform within the many sectors faced with overt and systemic racism, not just in America, but anywhere racism thrives and is a detriment to marginalized communities? Yes.

Overt racism and its expression via racial microaggressions inundates the workforce, education, government, healthcare, housing, banking and all day-to-day activities. Addressing these issues can seem like an ostensibly impossible task in the face of such slow progress in the fight for equal pay, good education, home ownership and generational wealth. Will we, as a country, eventually move forward enough that racial microaggressions are a distant memory? As I arrive at the conclusion that this potential buy will, indeed, fit my derrière, I hear, “Excuse me, ma’am. Can you let me know if you have any more of these shorts in stock?

Here we go again.