Catherine Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle, an unlikely art provocateur and descendant of the thirteenth oldest family in France, was born at a chateau near Paris in 1930. She arrived in New York City as a toddler, grew up as bilingual “Niki” on Park Avenue, summered on Long Island, was kicked out of several schools and was slated to become a debutante.

But she defied that role, among many others. As her ticket to freedom, teenage Niki eloped in 1949 with Harry Mathews, a nineteen- year-old from a wealthy Princeton family. Her first defiant act as a newlywed was fashion-related; forced into a second, proper wedding in a church by her mother, she wore a short blue satin dress instead of a traditional white gown. The bride and groom were both financially cut off by their families, and the newly impoverished couple resorted to stealing the luxuries (books and gourmet food) that they couldn’t afford.

But Niki didn’t hold a grudge: “I did not reject Mother. I retained things from her that have given me a lot of pleasure—my love of clothes, fashion, hats, dressing up, mirrors,” she wrote in Traces, her 1999 autobiography.

For nearly fifty years, Niki was celebrated as an artist, Vogue cover model, filmmaker, AIDS activist, author, jeweler, set and costume designer, performer, playwright, perfumer and icon. Her success was entirely self-created and she was a rebel in every aspect of her life. “Very early I got the message that men had power and I wanted it,” she observed in Traces. Niki’s versatility and drive are reminiscent of the multitalented powerhouse Rihanna, her take-no-prisoners attitude exemplified by steely Sansa Stark in Game of Thrones and her rakish bohemian lifestyle might even have impressed Keith Richards.

Niki’s modern attitude, personal style and artistic signature have inspired designers and artists alike for decades. At Dior’s Spring/Summer show in 2018, Maria Grazia Chiuri used Niki’s bold colors, design motifs (hearts, stripes, stars, flowers, polka dots) and patchwork on long skirts, jackets, even T-shirts, stockings and handbags. Millinery genius Stephen Jones recreated Niki’s signature veil-draped beret. Likewise, Anna Sui, Peter Dundas (formerly of Emilio Pucci), Julie de Libran (formerly of Sonia Rykiel) and David Koma all count Niki as an inspiration.

Early in her career, fashion paid Niki’s bills as she modeled for magazines including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and Life. The experience trained her eye and boosted her confidence. Harry recollected that Niki had a black pantsuit specially made in 1955, and fifty people followed her down the street in Italy when she wore it. Pants weren’t typical for women at that time. Early in her career, Niki customarily worked in sloppy, paint-spattered shirts and trousers.

Outside the studio, she favored the uniform of a black turtleneck accessorized with a crucifix on a chain. In 1968, she posed for Vogue in a black leotard and massive hair extensions. WWD covered one of her gallery openings in Paris, but ignored the art, instead reviewing the outfits of Niki and the “It girls” of the time. That same year, Vogue noted that her studio garb was white jeans and a T-shirt, but otherwise she was known to wear “the most romantic clothes in the world.” Niki’s version of boho included lace collars, long print dresses and dramatic big-brimmed hats. A photo from the ’70s shows her in an immaculate, white ruffled Victorian blouse and straw boater, daubing paint on a sculpture.

In 1965, Niki began a long association with Marc Bohan, the head designer at Dior. Bohan collected her work and also created custom pieces for her, including a long coat with enormous fur sleeves and a famous tiara of two intertwined snakes. Bohan paid Niki homage in 1984, placing her sculptures on the steps of the Grand Palais where the Dior collection was shown. But perhaps her most iconic fashion statement was the 1982 ad for her namesake perfume: a photograph of Niki, holding one of her snake sculptures, with a colorful snake painted on her face from forehead to chin, and a serene smile.

Niki and Harry relocated to Paris in 1952 with Laura, their infant daughter. There, Niki was unexpectedly transformed into an artist at age twenty-three, when she had a nervous breakdown. Between electric shock treatments in an asylum, she collected twigs and leaves from the grounds, which she then assembled and painted. “My mental breakdown was good in the long run, because I left the clinic a painter.” There were more shadows. In her memoir, Mon Secret, published in 1994, Niki revealed that she had been molested by her father as a child. “I had a big rage in myself,” she declared to an audience in San Diego. “I would have probably been in prison, or still in a psychiatric hospital, if it hadn’t been that art helped me to get out all of my very deeply aggressive feeling toward my parents, toward society.” Art was her salvation. Niki escaped the fate of her sister Elizabeth and brother Richard, who both committed suicide.

Health restored, Niki had a son, Philip, in 1955. Harry immersed himself in the literary scene and wrote a novel. In 1956, Niki had her first painting show and met Swiss artist Jean Tinguely. Four years later, she abandoned the children and Harry: “I didn’t want to worry about him, the children... or any other responsibilities,” she wrote. Harry lived with the kids in the fancy Seventh Arrondissement while Niki and Tinguely lived in an unheated shack on Impasse Roncin that had a dirt floor and no running water. They shared a toilet with neighbors Constantin Brancusi, Claude Lalanne, Larry Rivers and Yves Klein. Her relationship with Tinguely lasted a lifetime, through various incarnations, as he was also a reliable creative collaborator. When they were apart, Tinguely sent her love letters that opened into pop-up sculptures. Fame and success only enhanced Niki’s disregard for convention. A French documentary about the couple described them as “the Bonnie and Clyde of art.” Later, they took up residence in a former brothel outside Paris. He had lovers. She had lovers (male and female). Photographs of their orgies were casually displayed around the house. They finally married in 1971. Afterwards, Tinguely joined his pregnant mistress in Switzerland and never lived with Niki again, although they continued to collaborate on art pieces.

Niki first became known for transgressive performances with her “Tirs” (gunshot) pieces in the early ’60s. Cartons of yogurt, eggs, cans of tomatoes and bags of paint were glued to a piece of wood, and then covered with a thick layer of plaster. Dressed in a white jumpsuit, Niki shot at the piece with a rifle. Her messy avant garde presentations drew crowds in Europe and the United States, and even Jane Fonda watched Niki blast and splatter at an event in Malibu, California in 1962.

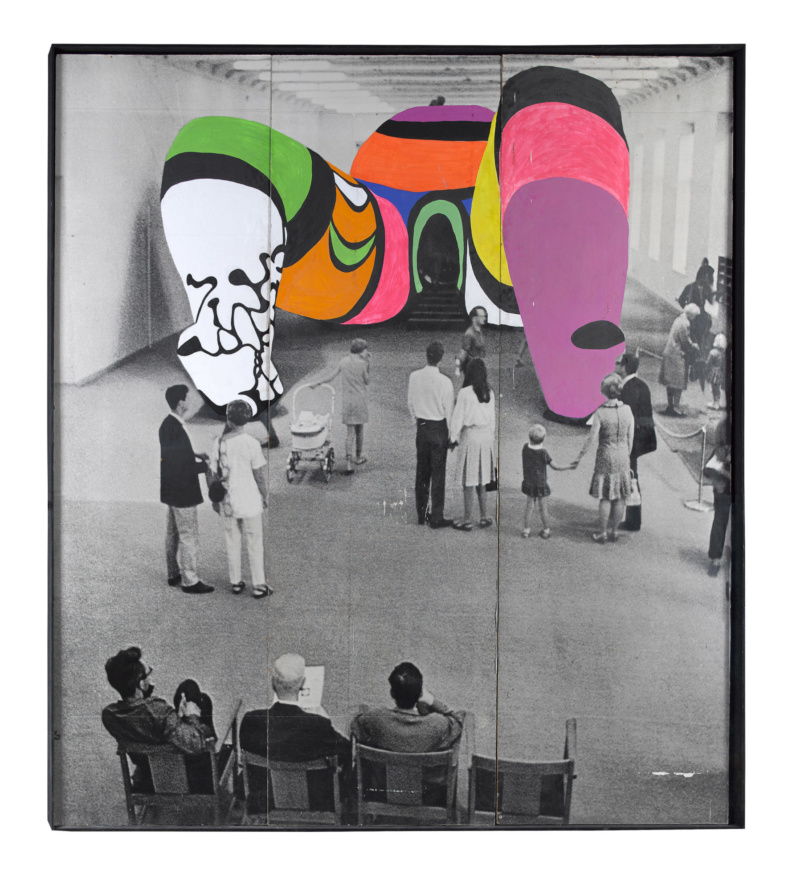

But, since the mid-’60s, Niki has been predominantly identified with her Nana sculptures—bulky, cartoonish figures reminiscent of fertility Goddesses with exaggerated breasts in brilliant colors and patterns (Nana is a French slang term for woman). The Nanas came in a range of sizes, although Niki favored super-scale: “I think that I made them so large so that men would look very small next to them,” she confessed in an interview. Her work reached audiences all over the world, from the Guggenheim Bilbao to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

In 1980, she began a laborious, seventeen- year project: the Tarot Gardens, constructed on fourteen acres of land in Tuscany. Inspired by characters in the Tarot Arcana, these Nana-esque structures, some the size of buildings, were cast in concrete and covered with glass and ceramic mosaics. For seven years, Niki worked and lived inside The Empress, a building in the shape of a huge woman, its extraordinary interior completely lined with pieces of mirror. Niki was constantly short of money for the enormous garden, which was partially funded by friends, lovers, patrons, her ex-husband and commercial ventures, such as inflatable Nana pool toys, jewelry for women and men and her perfume, its bottle topped with a stopper of two snakes. When her longtime assistant, Ricardo Menon, died from AIDS, she constructed a memorial grotto for him in the garden and became an early AIDS activist. She wrote a book, You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands, published in 1987, and produced an animated educational film about the disease.

Ebullient, defiant figures, the Nanas were also ultimately fatal. Toiling on the sculptures for years, Niki inhaled toxic fumes from the polystyrene, which affected her lungs. She died of lung failure in 2002 at age seventy- one. Not a woman to have regrets, she observed, “I have been a wild, wild weed. Done everything. It’s possible in art to be a rebel and experiment. Now I am much more concerned with bringing joy.”