For many of us, Nigel Poor has become a household name in the criminal justice reform space. Between her teaching at California’s San Quentin State Prison to co-hosting Ear Hustle—a Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast that tells the quotidian stories of incarcerated people—Poor’s work centers those defined in some way by the United States’ prison system. However, she didn’t start out as someone affected personally or through family, nor was she a vocal activist for mass decarceration. Her conduit to prison reform was something slightly unexpected: photography.

Poor’s more than 30-year career always orbited the idea of things people leave behind or entities society might undervalue at first glance. From capturing dryer lint and squashed insects to pursuing a project focused on over 100,000 fingerprints, Poor underlines that she has always looked “for unusual ways to explore life and the marks we make.” Conceptually, this led her to question incarceration, and how those of us outside of carceral walls understand individuals inside.

Her latest body of work, The San Quentin Project, amalgamates archived photos of San Quentin from the 1930s through the 1980s into a new book. With the help of some of her students inside the facility, Poor has created a compelling record of what life really looks like when one is separated from society. Her marriage of creativity and advocacy continuously informs a decarceration movement fueled by empathy.

Abigail Glasgow: Let's start with what led you to San Quentin State Prison, and eventually how you came to publish this book.

Nigel Poor: I got interested in prisons around 2011. I really didn't know anything about them. I started thinking about how people make a life in prison. What would you do when what many of us would consider our daily necessities and our freedom to move about is taken away? How do we make a meaningful life under difficult situations? I wanted to figure out how to get inside of prison, but I had no idea how to. I heard about an organization that, at the time, was called the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison. They were looking for volunteer professors to teach their onsite degree granting program. I proposed teaching a history of photography class like I do at California State University, Sacramento and taught that class for three semesters. I got to know a lot of the men inside, and importantly, they got to know me.

AG: And what does teaching photography inside look like?

NP: In that class, I used photography by well-known artists as a conversation starter. One of the things that I love about photography is that it’s this incredibly ubiquitous art form. Most people feel very comfortable looking at photographs. Whatever's happening inside that frame can be interpreted in so many different ways and by bringing in our own experience. So that was the premise I used with the men inside looking at photographs by all different artists: helping them realize that they could use these photographs to talk about their own experience.

Shortly towards the end of teaching that class, around 2013, I visited the office of Lieutenant Robinson—the public information officer at San Quentin—and he showed me this box of amazing archival negatives. That's what the book is based on.

AG: And had these negatives ever been seen before, or put on display?

NP: There were hundreds and hundreds of four-by-five-inch negatives that had been developed, but there were no prints. As a photographer, to see four-by-five negatives, which really aren't used that much anymore, I knew that there was something really amazing there. Lieutenant Robinson told me they were all taken at the prison. I started going through them and it was just a jumbled mess; there was no organization to it. But as soon as I started looking—I still get goosebumps when I think about this. Anyone who is interested in photography or archives would lose their mind when they saw these negatives. It was clear nobody had really done anything with them before. It was like this treasure waiting to be explored.

The few that I looked at while I was in this office were so intense. They were clearly showing everyday life in prison in a way that most people don't get to see. I asked if I could take some home and scan them, and maybe even do something with them. To my surprise he said yes. So I left that day with an envelope full of negatives. It was just unbelievable what was there. I knew I wanted to do a project with them, but I also knew these were historically significant and needed to be preserved so they weren't just moldering away in their boxes.

AG: Do you know who took them?

NP: They were taken not by artists, but by correctional officers to document what was happening inside the prison between the 1930s and the 1980s. In a lot of cases, it was to document crimes—murders, suicides and fights—but also programs that were happening, visits, dignitaries coming in. As I looked at them, I realized that of course it started as a job, but some of the photographs are so well framed so I'm guessing that the correctional officers eventually just got to enjoy it. They're not attributed to any one person on the negative sleeve. Sometimes there will be a date with a brief description like “murder in the left lower yard” or “Mother's Day 1972.” It's a beautiful mystery in some ways.

NP: The first thing I was going to do was just put them into different categories. But then I remembered one of the assignments I had done with the Prison University Project. The men had images by well-known artists that they mapped and dissected. I wanted to do the same thing with these archive pictures, because the men at San Quentin have something to say. And they're going to see something in the photographs that no one who has never been incarcerated is going to see. I needed the guys inside who had experience to escort me around the pictures and explain what they saw in them. That's how I started collaborating with the men inside on the book. I talked with a few men who had been in my class who love photography and we got a group of about 10 guys together. We met every couple of weeks informally in the prison and I would bring in 20 to 25 prints of the negatives. The guys would select which ones they wanted to write about, take them back to their housing unit for a couple of weeks, work on them and bring them back. And then, next meeting, we’d talk about what they saw in the photographs.

AG: And give me an example of something that one of your students saw in a photograph that maybe you wouldn't have seen.

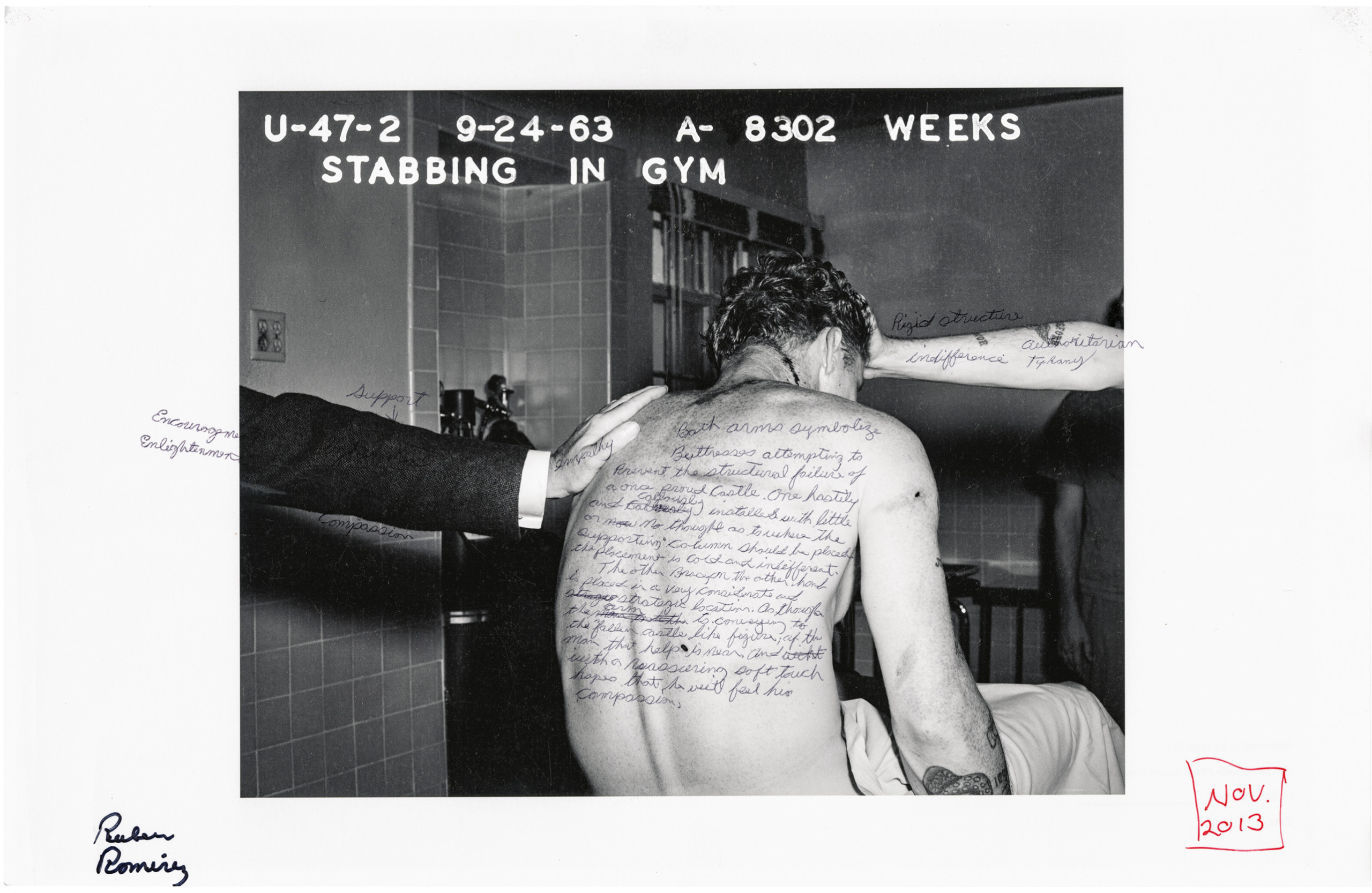

NP: There's one in the book called “stabbing in the gym.” It's by Ruben Ramirez. I've looked at this picture so many times and it never ceases to amaze me. It's a violent picture. It's a man who's clearly been stabbed a couple times, and he's being held up by two arms: one has a suit on and the other is a bare arm with a tattoo.

Ruben writes about looking at this body in architectural terms, as if it's a cathedral. He talks about a once proud cathedral that's falling down now being buttressed by these two arms. One arm represents tyranny and authoritative rule, the other represents care and love; and this man is struggling between the two. It almost fills me with tears when I read it. Instead of talking about the man's remorse or rehabilitation, he's talking about being a fallen castle; something that had substance, something that was proud. And it's such a poetic and tender way to talk about a really difficult subject.

AG: What do you hope people will take away from reading your book?

NP: In the case of the cathedral example, Ruben completely educated himself in prison and talks about that image in a way that's profound and emotionally very available. He didn't talk about a stabbing in the yard, he talked about something much more interior. My hope was when somebody read that, they would realize that every image in the archive had the possibility of having a much deeper explanation.

The project is about asking people to reconsider who is in prison, and how prisons should function in our society. The only way that's going to happen is by having people who aren't like-minded see this work and be changed by it. From the beginning, my fantasy was that someday this would be a book that could be more widely shared.

AG: In the introduction of your book you say you didn't go inside because you had a family tie to the system, nor were you involved in the activist side of things. Now that you have been in this world for 10 years, what have you learned? Do you now identify as an activist?

NP: I've changed a ton. I think when you go into a new situation, you're smart to go in as a quiet observer and have patience to let things develop over time. And more importantly, give people time to get to know you. I’ve been going into prison for 10 years. And I think teaching for the first year and a half was great because it allowed me to learn more about prison, but I always say it allowed people to get to know me too—who I was, what I was about. I learned so much more about who is in prison and what things need to change.

So, I guess I would call myself a quiet advocate. I'm not overly political. I like to use art to give people the ingredients to make up their own mind about what should change. When you try to tell people what they need to think, you run up against so many roadblocks. But if you sneakily come in through a backdoor, you have a much better chance of changing people's minds. I didn't go into prison thinking I wanted to change people's minds about prison. But as I spent more time there, I’ve become an advocate. I want to use the arts—whether it's photography or podcasting—to work in collaboration with people who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated. I want to tell everyday stories and show the connections between people who are inside and people who are outside.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.