“I consider myself a weaver in many ways,” says New York-based artist Nari Ward, whose survey “Nari Ward: We the People” opens today at the New Museum in lower Manhattan. Drawing on Ward’s twenty-five-year-plus career, the exhibition entwines over thirty sculptures, videos, and paintings, as well as the large-scale installations of discarded materials and recontextualized objects that establish Ward as one of the generation’s foremost sculptors.

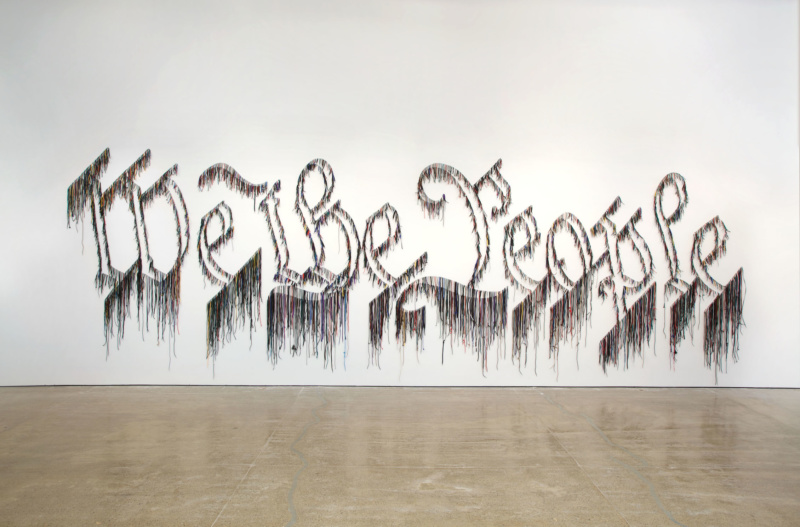

Scavenging detritus from the streets of his Harlem neighborhood, he confronts the complexities of African-American experience, Caribbean diaspora identity, and Manhattan gentrification through a visual language that references the folk traditions and creative recycling of his native Jamaica. Baby strollers, television sets, carpet runners, plastic bags, and soda bottles are transformed into symbolically loaded assemblages that, as New Museum director Lisa Phillips describes in the show’s catalogue, offer viewers space to reflect and meditate on memory and community. As one of the 1990s’ most emblematic artists, Ward is part of the group that tilted contemporary art toward a more political stance. Decades later, in likely his most recognizable artwork, Ward presents the preamble to the US Constitution in an 8 x 27-foot sculpture—We the People (2011)—each script-font letter formed by shoelaces that dangle from the gallery wall.

“I’m generally associated with the found object art movement,” Ward explains. “Once I pick these things up on the street, it then becomes: what world do they exist in? And then, that world has to be first constructed in my imagination.” For this show, curators Gary Carrion-Murayari and Massimiliano Gioni return several of Ward’s iconic sculptures to the New Museum, including Carpet Angel (1992), Hunger Cradle (1993), and what is often considered his seminal work, Amazing Grace (1993)—an enormous, immersive encounter rooted in the materiality of Harlem, but which has resonated across countries and contexts.

“There’s a kind of directness in terms of people thinking they know what the thing is,” he says, of the repurposed objects and their metaphorical weight. “That is why I choose something that is recognizable. But then there’s also a desire for it to become more than what it is, and [it becomes] even more ambiguous in terms of the expectation for it.”

Originally installed in 1993 in a former Harlem firehouse (now his full-time residence and studio, where we met), Ward amassed hundreds of ramshackle baby carriages, abandoned first by parents and subsequently appropriated by homeless New Yorkers for their belongings. Ward began collecting the strollers as a student-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. A reaction to living and working at the center of New York’s AIDS and crack epidemics, Amazing Grace comprises a stroller mass enveloped by an extensive oval-formation; visitors perambulate a pathway of flattened fire hoses, while “Amazing Grace,” sung by Mahalia Jackson, loops overhead. In 2013, the New Museum presented the installation in its annex gallery space, where it felt at once devastating—a raw visualization of urban blight and New York’s income chasm—yet uplifting, as the soundtrack provides a haunting element of redemption.

“A lot of the work comes from trying to create a puzzle for people to see themselves in and look at the situation in a different manner than they would have come to,” says Ward, who describes his newer sculptural forms as transporting the viewer to a separate space within a history they already know. Most notably, in his abstract, copper sheet Breathing Panel series (2015) and his newer Breathing Circles pieces (2018), Ward repeats a central diamond motif of cut-outs surrounded by copper nails that references the Congolese cosmogram, an ancient African prayer symbol. During a visit to the First African Baptist Church in Savannah—part of the Underground Railroad—Ward confronted the decorative symbol drilled into a church floor over twenty times. They were, in fact, used as breathing holes for slaves to hide and move secretly beneath the floorboards during their escape.

“When I realized it was a way to vent the slaves hiding underneath and I was standing in this space, there was a powerful reaction,” Ward recalls of the epiphanic moment in 2015. But he hesitates at characterizing Breathing Panel or Breathing Circles as directly referring to African-American history. "When I engage with the Underground Railroad signifiers and mythology,” he emphasizes, “I really wanted it to be not just an African-American, but an American narrative." This realization— that our nation’s DNA is tightly coiled around these stories of escape—is paramount to his pieces, he adds.

Recalling grade school, Ward recounts the perils of history textbooks: how, in prioritizing certain details, they neglect crucial notions of collective memory. “I wanted to have this one narrative supersede all of them,” he says of the church iconography. “It’s not about changing people’s world. It’s about creating another moment for them to grow, and in that growing maybe something will keep happening.”