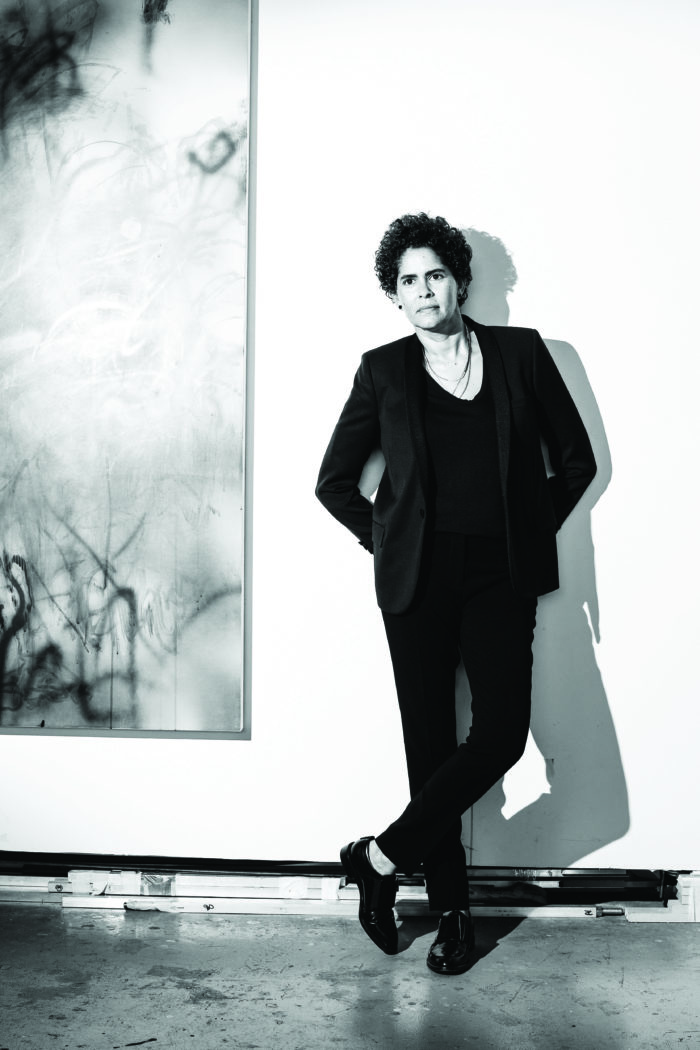

Composing a feature on Julie Mehretu is a monumental task as words are inadequate to describe the depth, breadth and complexity of her work. Nevertheless, when I visit the artist’s studio on a humid, late August afternoon, Mehretu greets me at the door with a warm welcome. After a brief walk around the expansive light-filled space we settle into a comfortable area that at first glance seems to be a reclusive corner.

Surrounding us are the new paintings Mehretu will be displaying at Marian Goodman Gallery in “Hoodnyx, Voodoo and Stelae” this month, which are simultaneously exuberant and restrained, yet they retain Mehretu’s characteristic precision. She is not only preparing for her New York exhibition at Goodman, but also finalizing details for a European traveling exhibition and continuing her work, at a church in Harlem, on her much anticipated SFMOMA public commission.

The issue is that Mehretu cannot be reduced to any of the normal art magazine pegs: virtuosic skill, the art market, glamour, cross-disciplinary collaboration, gender, race, sexuality, intellectual rigor. As we begin the interview it quickly evolves into a conversation, in which I have the opportunity to test new ideas alongside a noted cultural producer in the art world and in global politics alike. As a result, the best I can do to create a substantive portrait of Mehretu is to provide a set of paradoxes, questions and uncertainties.

Mehretu herself gives me a roadmap to navigating this process—much like the geographical and ethnographic nebulae in her paintings—and it is the best way to understand her work: “I have insisted on abstraction. There’s an opacity to my paintings that I hold on tight to. Edouard Glissant said, ‘We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone.’ ”

What would it mean for art historians and critics to understand Mehretu’s work as an assertion of the right to not have to constantly explain one’s self? It is true that her paintings have been discussed, and rightly so, with regard to their revolutionary content—their connection to the Arab Spring, non-Western infrastructure, forced migration and a non-hegemonic relationship to modern painting, to name a few. Mehretu, however, reminds us that there is an interpretational bind here: “It’s hard to simply accept and understand that a woman of African descent is making large, abstract paintings. Generally, the type of black artists we celebrate are artists who are dealing with their blackness, or otherness, in a way that offers an ‘insight,’ transparency, bombast or a claiming of a certain kind of negritude. It is a binary idea of what a black artist can be. You should be able to do that, and also something completely opposite.”

“These are complex, time-based paintings that you have to interact with. You move through them geographically in a way that goes beyond the cerebral. It is a felt experience."To be an artist, one must surely be political, but one has the right to be confounding, enigmatic, beautiful, to be intimate with their materials, to be nothing at all. How, then, can we productively learn from Mehretu’s recent landmark exhibition in her home city of Addis Ababa without resorting to neo-colonial truisms about artists of African descent? Mehretu has always utilized art as a vehicle for global social change; she recently co-produced Difret—a film by Ethiopian director Zeresenay Berhane Mehari about child brides and marriage-by-abduction in the country. Even so, this was her first show in Ethiopia, and despite certain challenges that arose, Mehretu and her colleagues proved that community-based collaboration could create extraordinary artistic experiences. “There are very few art institutions in Ethiopia, and they are very poorly funded. But Ethiopia is the fastest growing economy on the continent. Addis is booming in certain ways, and it has the possibility to be an amazing engine of cultural and creative development,” explains Mehretu. “Two dedicated cultural producers came together to make this show happen, the pioneers Elizabeth Giorgis and Dagmawit Woubshet. I’ve always engaged with Ethiopia as a place of my origin, my family, but in this case, I was able to come as an artist, a queer artist, and be who I am. As part of the programing around the show, we organized a symposium, where we invited writers, architects, historians and curators across disciplines and from a multitude of places. It was phenomenal, a room full of almost a hundred people, mostly Africans, with at least 10 different countries on the continent represented –Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, Cameroon and of course Ethiopia. The relationship and development of that type and level of inter-continental discourse and exchange has to continue.” Mehretu describes the show as both a sociopolitical, collaborative and multi-continental happening, but most fundamentally, a chance to talk to people who are largely removed from the international art scene about the properties of the paintings themselves.

We must, then, understand Mehretu’s politics alongside the deeply forceful presence of her paintings, and not just biography. “These are complex, time-based paintings that you have to interact with. You move through them geographically in a way that goes beyond the cerebral. It is a felt experience,” she says. “I’ve studied painting my whole life, and I’ve studied it seriously. Paintings choose their audience—the people who will spend a couple of hours looking.” There is no better way to illustrate this sentiment than considering Mehretu’s recent collaboration with the Dutch National Opera and Ballet for the set design of director Peter Sellars and composer Kaija Saariaho’s Only the Sound Remains—a combination of two short contemporary operas inspired by traditional Nôh dramas (which Mehretu studied in preparation for working with Sellars).

Originating in 14th-century Japan, the Nôh is the oldest form of theatre that is still performed—a veritable combination of history, tradition and innovation. In this way, performance and music provided a platform for Mehretu, wherein audiences were able to look closely and live differently with her paintings. Drawing on this love of music, as well as her research into the set designs of various modernist theatre projects, such as collaborations between Robert Rauschenberg and Merce Cunningham, Mehretu created something unequivocally spectacular. She also gave us a taste of the story’s unexpected gay romance, but you will have to be content for the moment with a bit of atmospheric imagery: “One of the central characters, Philippe Jaroussky the renowned countertenor—a ghost—actually emerges from my painting. You can see through the painting when it’s lit a certain way. It’s space; it’s not space. It is ephemeral. All of this happens on the stage. The marks become agents within the space, and the inside of the painting is the past, which is also the future. I have been informed and permanently stamped and shifted by music. It was an incredible experience to design the sets, and I hope to do more.”

An hour and a half passes and we emerge from the interview with more questions than answers, but as Mehretu suggests, that is a good thing. “Art’s job is to complicate as much as possible. That’s what we want art for; that’s what we want poetry for—to be full of contradictions, or to expose contradictions. That’s where radical possibility exists. Imagining other possibilities is how things change.”