The photographer John Edmonds first picked up a camera when he was 15 years old. His older sister had a Kodak point-and-shoot camera he would use to capture his life in Washington, D.C. At some point, the young lensman decided that he would picture black boys coming of age.

Almost 15 years later, those early images continue to inform his work: In a 2016 public commission, Edmonds mounted an image from his series Hoods—of hooded figures whose backs face the camera, obscuring their identity—on a 48-foot-tall billboard on West 29th Street in Manhattan. The billboard, presented by the arts organization 14x48, was a way of discussing racial profiling and how identity is imposed and fashioned. “Making photographs is like a way to learn how to see or understand how you see the world around you,” explains Edmonds, who received his M.F.A in photography from Yale University School of Art in 2016. “That was my main reason,” he says, for picking up a camera.

In his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, “Higher,” on view through June 3 at Ltd Los Angeles, Edmonds presents Du-Rags, a series of closely shot images of black men wearing the headscarves the show’s name references.

In Untitled (Du-Rag 1) and Ascent, Edmonds presents black men’s heads wrapped in white do-rags with an almost celestial quality on Japanese silk. For Edmonds, through repetition, the objecthood of the do-rag reveals itself as a symbol of American and black culture, identity and intimacy.

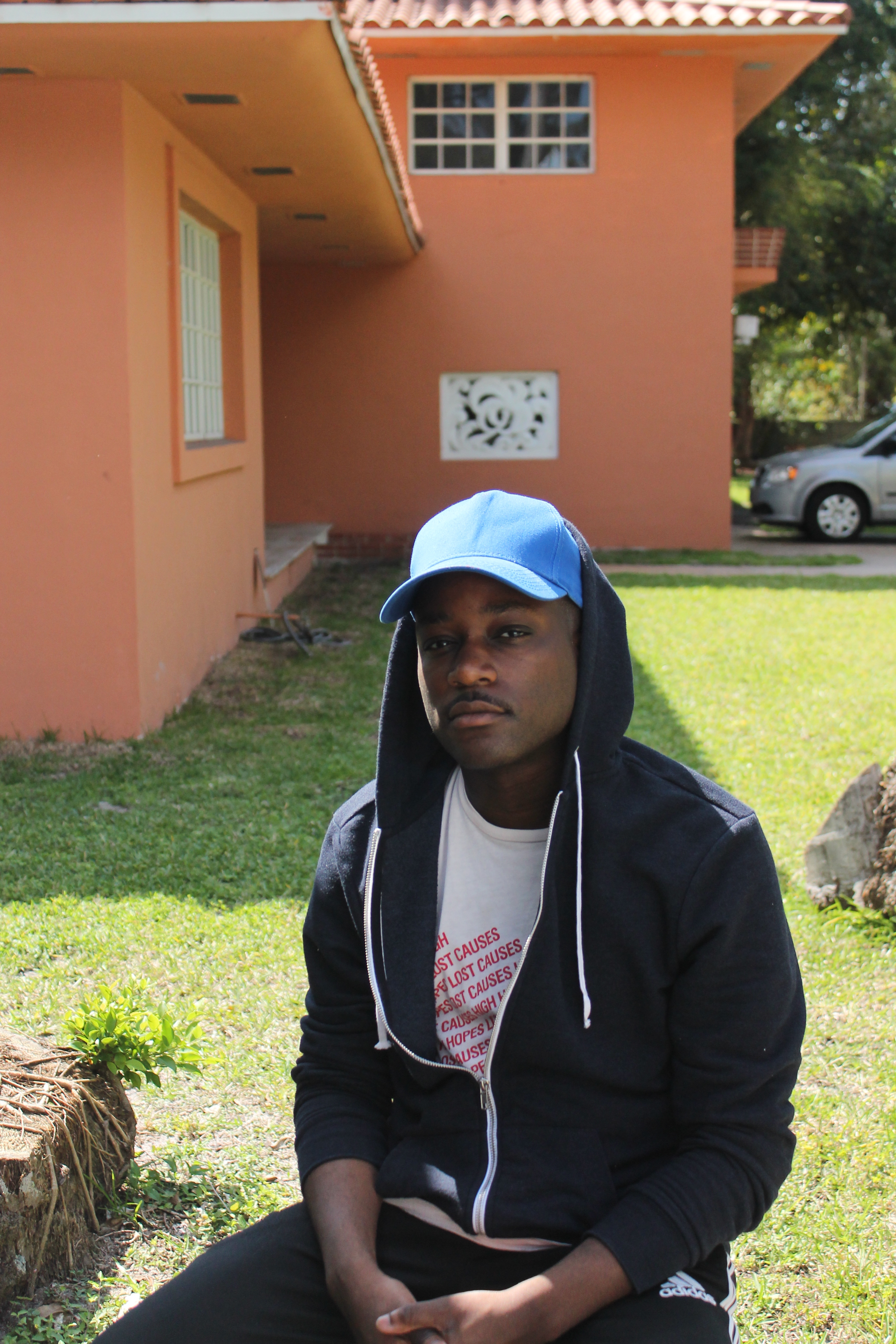

“I think in all my work, there's this close look at not just beauty, but also presentation: How one presents himself to the world around them and how different types of presentation are commentaries or forms of resistance,” he says. As someone who mainly finds his subjects on the streets and subways of cities like New York and his native Washington, D.C., a process Edmonds likens to model scouting, the clothes that his subjects wear often take up most of Edmond’s frame. “The head is so interesting to me because it’s where people first look,” says the artist. “I always think of what someone puts on their head as a way to immediately say something about how they feel about themselves or how they want to convey a certain kind of emotion or attitude.”

His intimate pictures of black males have won him praise from artists like Carrie Mae Weems and Mickalene Thomas, who included Edmonds’ Untitled (New Haven), a nude of Edmonds and another male laying in bed, in the seventh iteration of her curatorial series “Tête-a-Tête” at David Castillo Gallery during Art Basel Miami Beach last year. “His work embodies the complexity of our social, political and personal mythos of the black body in a beautiful and subtle way that stays with you, like Moonlight,” she says. “He not only redefines how we see the black male body but allows us to embrace its beauty.”