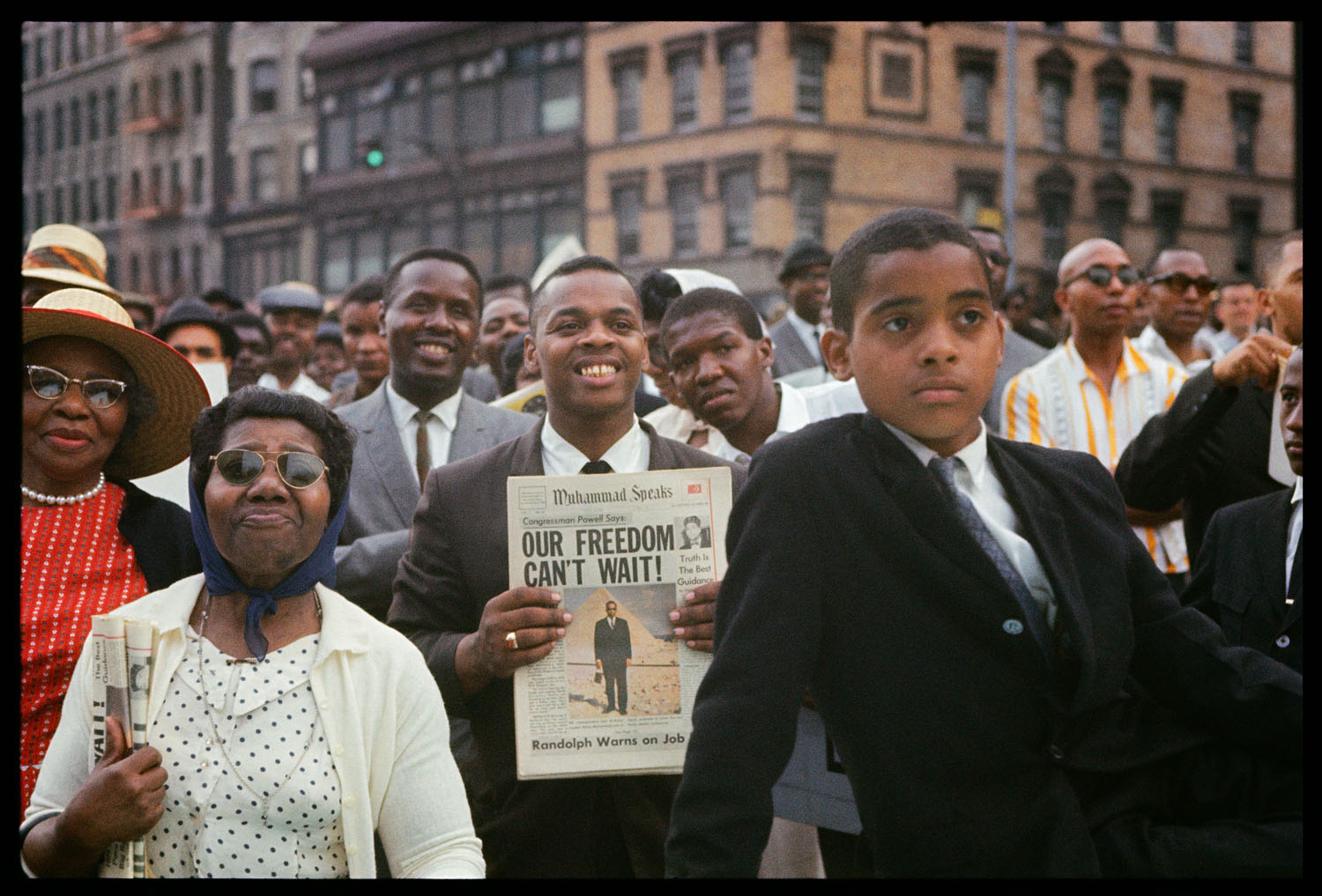

There’s an argument to be made that Gordon Parks is the greatest documentary photographer the United States has ever birthed. Others come to mind—Robert Frank and Larry Clark have often stood out to me as particularly special, and one could argue that William Eggleston and Garry Winogrand nearly fit the bill—but none captured the blistering Americanness of America, both in its aspirations and in its consistent, heartbreaking inability to live up to them so skillfully as Parks. And while no cry has become a more oafish, self-aggrandizing cliché recently than that of “now more than ever,” a yawp which implies periods of tranquility rather than periods of complacency with a deadly system—maybe “shit remains fucked” is a more accurate way to frame it—I do catch myself agape by the timeless relevancy of these images, many of which are 60-plus years old and could have been taken yesterday.

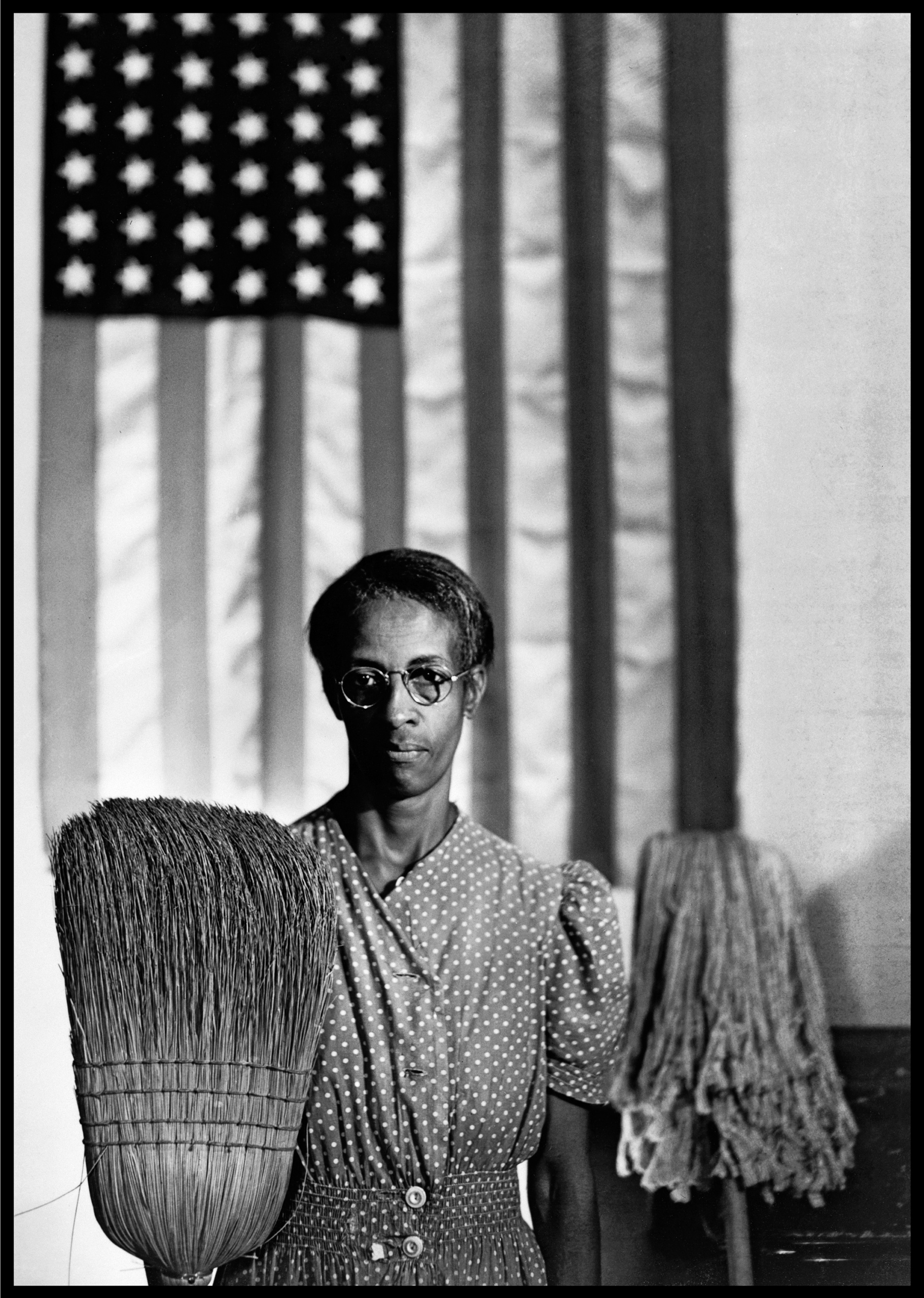

American Gothic, 1942, by Gordon Parks. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

American Gothic, 1942, by Gordon Parks. Copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. Courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Taking up both of Jack Shainman’s 20th and 24th Street galleries in Chelsea, Gordon Parks’s "Half and the Whole" offers a fairly sweeping view of his life behind the camera, with photos from 1942 to 1970. Images from a number of his seminal series fill the two spaces, including works from “Invisible Man” and “Segregation Story,” as well as a number of photographs he took for Life magazine, where he was the first Black photographer on staff. There are photos documenting police brutality protests as well as blunt images of rural and urban poverty and the Jim Crow South. And of course there are images of unbridled grace in the midst of it all, with works like Boy with June Bug, Fort Scott, Kansas, a 1963 shot of a young boy who has tied a june bug to a string and who rests in some tall weeds, eyes closed, as the bug crawls along his forehead. If I could live with any photograph in the world, it might very well be this one.

Another photo on view is Parks’s most well-known and widely-circulated: the 1942 image American Gothic, Washington D.C. (originally titled Government chairwoman, Washington D.C.), a portrait of Ella Watson, a woman whom Parks got to know over the period of several weeks he spent on a grant in the nation’s capital, photographing Watson at home, at church and at work. “I was like a kid about Washington—excited, thrilled. I was dumb enough to regard it as the symbol of everything wonderful in the United States,” Parks told Ebony in 1947, later adding, “I wanted to photograph every rotten discrimination in the city, and show the world how evil Washington was.” American Gothic shows Watson standing at her place of work, cleaning government offices. In the photo, she holds a mop in one hand and a broom in the other, each implement upwards like the pitchfork in the eponymous Grant Wood painting. A massive American flag swallows the portrait’s background. Remember the images we saw earlier this month, of Black and brown people cleaning glass and debris from the Capitol grounds after a mob of white supremacists ransacked the place? Shit remains fucked.