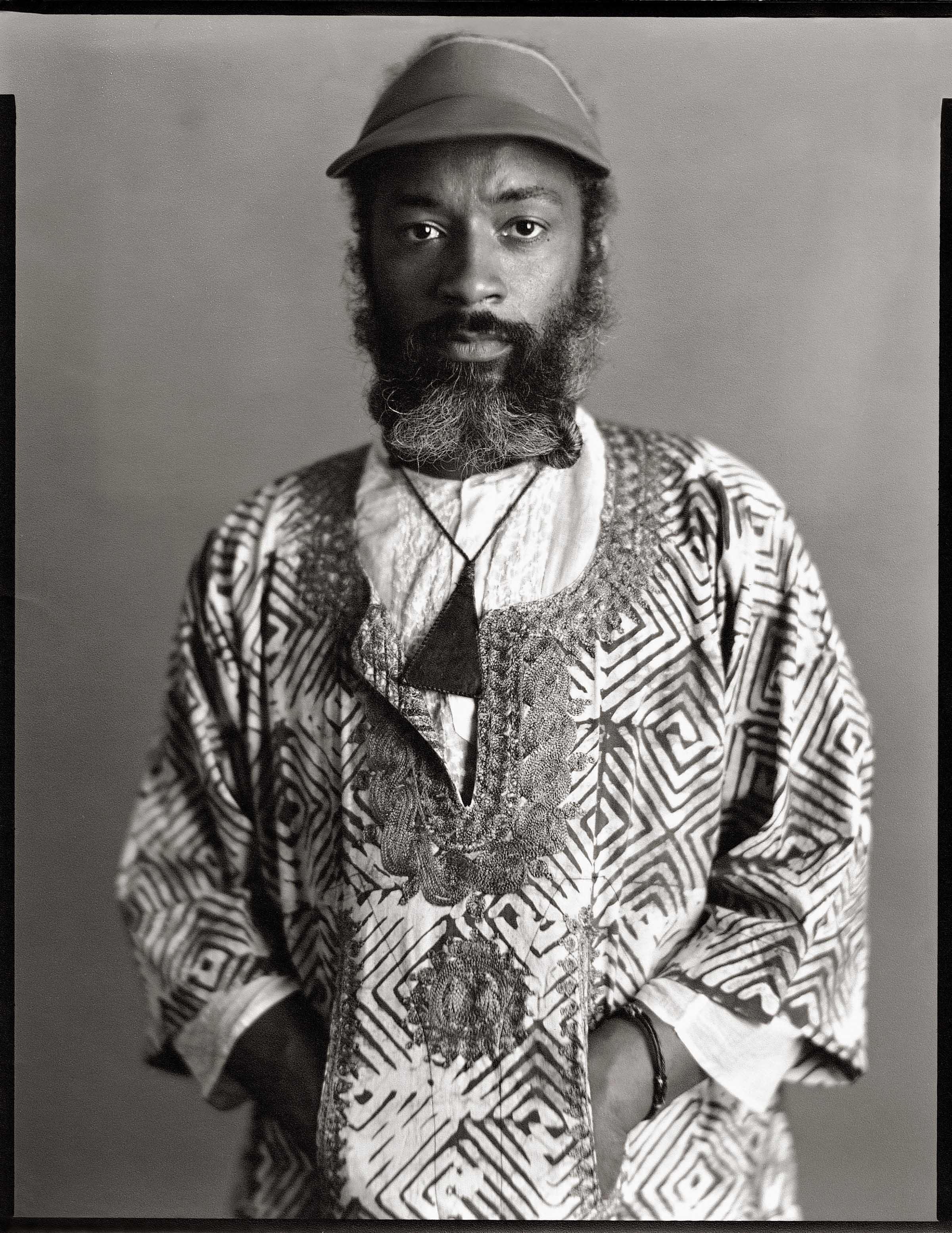

In celebration of the May 18 opening of David Hammons’ exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles—his first in over 45 years in the city where he attended art school and lived in the ’60s and early ’70s—we asked a group of artists with various techniques to reflect on how Hammons has informed their own practices and how his legacy lives in their work.

Since the 1960s, the artist David Hammons has made amorphous and ephemeral work that resists easy categorization. He has created performative body art (greasing and pressing himself against paper), public interventions (first lobbing a pair of sneakers over a Richard Serra sculpture in Lower Manhattan and then returning a few years later to urinate on it) and readymade sculpture (fur coats doused in paint).

Much of Hammons’ work has presaged the upheaval of urban life, often black urban life. He raised 30-foot-tall basketball hoops studded with bottle caps in Harlem and downtown Brooklyn before those neighborhoods experienced gentrification. He sold snowballs outside the Cooper Union three decades before the historically free art school began charging tuition. He mounted the hood of a sweatshirt lopped-off from its body 20 years before that piece of clothing became a symbol of a reignited civil rights movement.

As actively as his work lives in public, Hammons, now 75, has resisted speaking directly about it—or about anything at all, for that matter— allowing instead for the work to breathe on its own. Along the way, he has expanded what it means for something to be called art and what art is capable of.

Radcliffe Bailey Growing up in Atlanta, one of my first encounters with Hammons’ work was a piece of public art, Free Nelson Mandela, 1987, done before Mandela was released. I remember knowing the work before I knew who did it, and when I found out, it had this whole other dimension. His work was a performance. I remember walking through the park and seeing bushes growing around it and evidence of a homeless person right up under it, which made me feel like I had just stumbled upon a work in action.

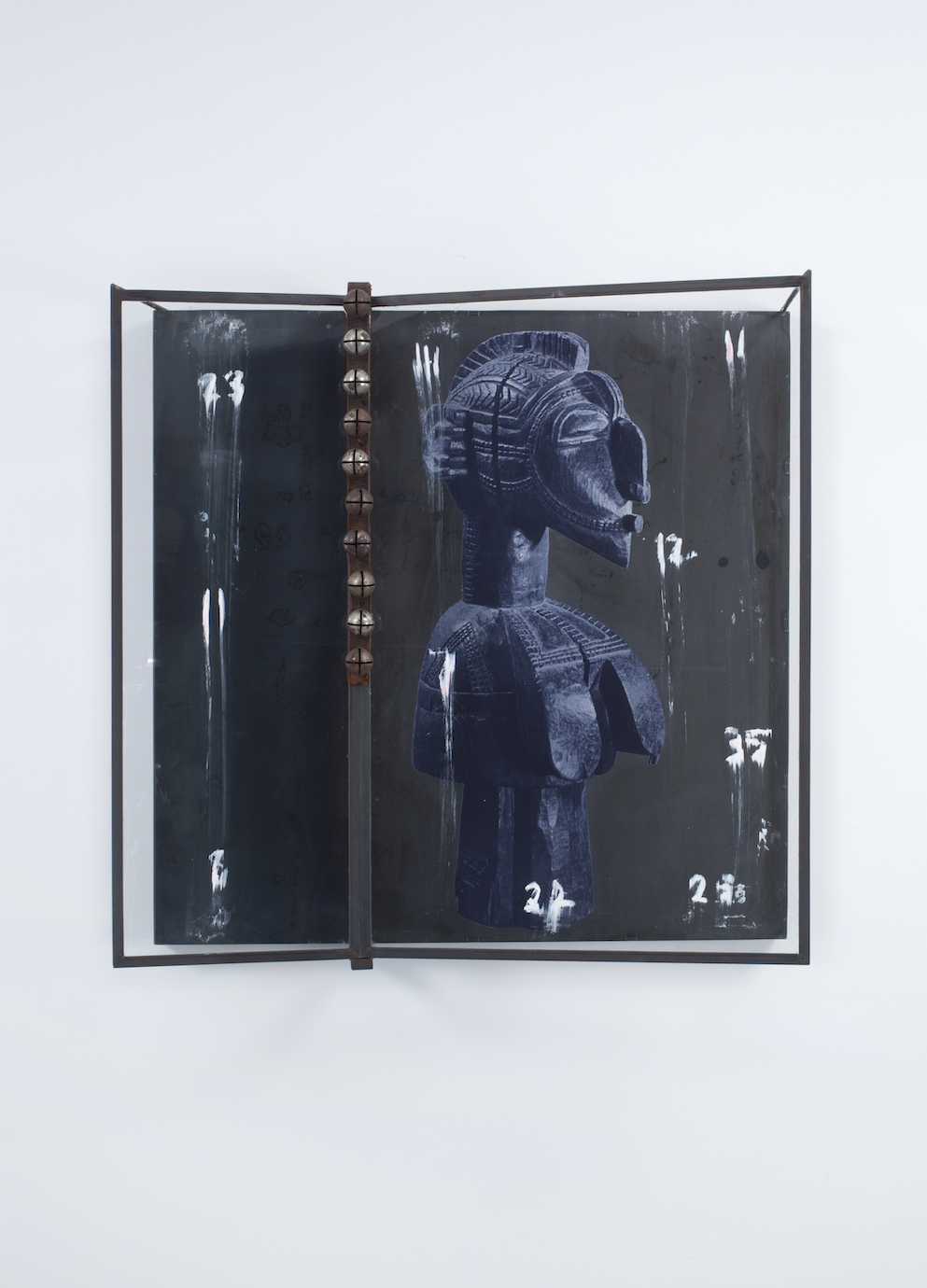

There was a traveling show at the time I was in school, when I had a lot of questions about what I was doing and where I was going. I remember seeing the bottle caps twisted together like cowrie shells turned into currency, which took me back to the other side of the Atlantic and back again. Early in my work, that influence of things having layers—I realized I didn’t have to be over the top, and it gave me a certain confidence in the materials I used. Hammons has a poetic way of saying things, like Amiri Baraka. One thing I respect is that he has created his own rules, his ability to forge a space outside of the white walls—I think of Miles Davis turning his back to the crowd. It resonates and speaks to the souls of black folks.

Keltie Ferris I make Body Prints that are greatly indebted to the body prints of both David Hammons and Jasper Johns. I was searching for a way to put my body into my work, to use it as a tool, to state as clearly as possible the point of view from which I make art and see the world. I make my body prints in the same two-step process of these two artists: I cover myself with oil, imprint myself on paper, then dust pigment across the paper, creating an image.

I was drawn to the intimacy of the Hammons and Johns technique of working. It felt so bare, and photographic even, yet also strangely not revealing of me as an individual, but more as a type. It revealed and even heightened my queerness and androgyny. I hadn’t explicitly put that in my paintings before this. It felt like acknowledging the elephant in the room.

Rainer Ganahl In 1993 in Tokyo, I spent several afternoons on a bench with David Hammons watching people go by, and we discussed our works. He showed interest in a piece I was creating for a museum show organized by Tim Blum in Japan, which was focused on a project where I was learning Japanese as my art practice. The project was a way to not speak for another culture but to acquire the tools to listen. It was influenced by Edward Said’s Orientalism and his criticism of cultural hegemony. In 1999, I switched to learning Chinese as part of this same artistic practice, and it still occupies me today. It was also Said who quoted Napoleon in Egypt, saying, “Nous sommes les varies musulmans” / “We are the real Muslims.” I wanna be Chinese is my way of playing with this form of cultural incorporation, which resembles some of Hammons’ work and the way he plays with cultural appropriation, like with his magical snowball piece where he mimics street vendors in Harlem.

Theaster Gates In terms of living artists, David is easily one of the most important influences on and guides of my art practice. Some of his influences— Duchamp, Marcel Broodthaers — these are people whom the conceptual bend of my practice favors. Part of the reason Hammons’ work resonates so much is because over the four decades he’s been active, he’s had a tremendous amount of what I would call restraint, but it’s also an unwillingness to fully participate in the dynamics of the art world as it’s dictated. That kind of intentional—what feels to me a kind of black resistance to the market underbelly, it’s also a tremendous strategy that allows him to leverage his creativity to do great things and benefit from the market, which is just genius to me.

The works that have had the most impact on me are: first, his snowball project that demonstrated a kind of determinism that, as his social successes increased, there was still the truth of his invisibility as a world-class artistic practitioner. The ways in which he’s always been an active social participant while making the most rigorous and tough objects ever is completely inspiring to me. The second is the body prints, where it feels like, in some ways, Hammons is making not just a self-portrait but a mockery of the history of portraiture, experimenting with essence and shamanism over realism. The body prints offer spiritual and emotional residue, and they act like artifacts of the immaterial world, more than the material world.

There’s a kind of confidence that I feel is generational, born out of the fact that for so long black artists were overlooked and not directly engaged. I think Hammons bridges the gap between the new preoccupations with Sam Gilliam—Gilliam being of a generation that didn’t benefit at all from a belief in their abstract expressionistic tendencies—and then with Hammons, who is performative, conceptual, present in the community, doing the hardest, most rigorous work—he catches the tail end of a market hot for black bodies and black images, but 60 years into his practice.

Hammons functions for me as a bridge, back to Lorraine O’Grady, Elizabeth Catlett, Stan Douglas and Kerry James Marshall—who’s slightly more of an LA peer to Hammons, but they both have a kind of commitment to a quiet, hermit-like ambivalence toward the market while sharing a deep respect for art and artists. I feel so fortunate that they swing just far enough to touch me while they’re living.

Jill Magid There are a few of Hammons’ works that have always resonated with me and that I go to in my mind often. I learned about Bliz-aard Ball Sale, 1983, first from the photographs outside Cooper Union, where I teach. That sidewalk is forever for me the site where Hammons sold snowballs on a rug. His work feels that way to me—alive and present in the city, as if through his work he is digesting the city and his experience as a black man within it.

I read somewhere that Hammons takes race and class as Duchampian-readymade. I think that’s true. With In the Hood, 1993, for instance, Hammons makes us notice that a hoodie isn’t just a hoodie.

Abraham Cruzvillegas David Hammons has been one of my main influences since the first time I saw his work. He made me reconsider my own experience and identity as an unstable material ready to be translated into pure instability, contradiction, and humor. He puts together all of the tools, languages and discourses from our genealogies as artists into a deep, strong, but simple way of making powerful and funky statements for the future of art.

David Hammons at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles runs May 18 through August 11, 2019.

This story was originally published in LALA Magazine.