Over this last year, I have been captivated by the works of Ode, Giorgia Narciso and Luana Vitra. While I am struck by their handling of archives and their visual articulations of movement, touch and sound, I am most impressed by their ability to formulate a practice that feels uncategorizable. Like many young artists in Brazil today, Ode, Giorgia and Luana are creating works that are informed by multiple histories.

Multidimensional and sensorily-driven, they depict the complexity of Brazilian identity from the perspective of their individual human experiences, intentionally challenging the common practice of defining art from one of the most populous countries in the world within one single category. We didn’t speak about the details of their practices directly, but we did speak of dreams, memories, love, and the ways in which the senses inform their work. It’s exciting to see young Brazilian artists unapologetically taking up space in the art world by speaking for themselves, on their own terms. In doing so, they are paving an expansive path for Brazilian artists and creating new possibilities for what “Brazilian art” can be.

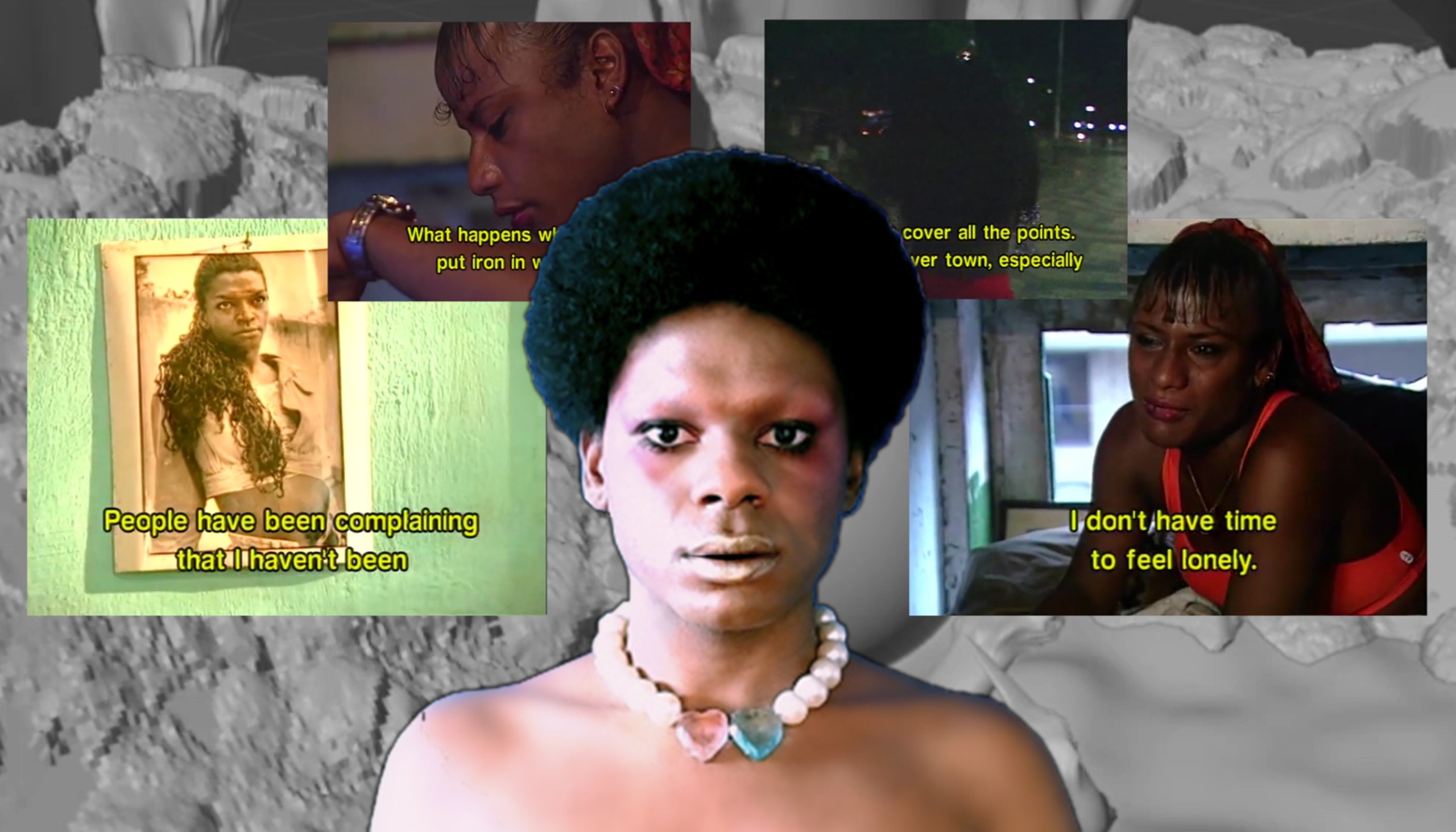

Ode

June Canedo de Souza: What is your relationship to dreaming/dreams?

Ode: “I think the dream fertilizes life and avenges death.” This is the first sentence in the book Não vão nos matar agora [They won't kill us now] by a great interdisciplinary artist friend, Jota Mombaça, which was articulated by the writer Conceição Evaristo during her conversation with Jota on the occasion of the Women in the World (WOW) Festival in November 2018. The preface of the book is called “Letter to those who live and vibrate in spite of Brazil” and it ends by saying that where we have been plundered, we have become more than they carried away; where we have been hurt, we have become more than an effect of pain; where we have been imprisoned, we have become more than captivity; where we have been brutalized, we have become more than brutality; and where we have been murdered, we have become older than death, more dead than dead. In this way, despite Brazil, my relationship with dreaming and dreams is uncertain and impossible, yet simultaneously a commitment to a radical imagination that instilled in me what is yet to blossom.

JCdS: What are some of your earliest childhood memories?

O: Rice, beans, torresmo, macarronada and caipira chicken, religiously, every Sunday at my paternal grandmother's house. My mother listened to the song "Verdade Chinesa" by Emílio Santiago while cleaning the house on Saturday afternoons. My father took me everywhere on the back of a bicycle, as he only had money to buy a car after I was an adult, and took me to eatpastel made of corn flour and stuffed with ground meat and drink sugar cane juice in the municipal market of Itajubá, my home town. My imaginary friends were named Bessa, Bussequela and Marcos.

JCdS: Of the four elements, which do you feel most connected to and why? How do they influence your art practice?

O: I feel most connected to air, because currently the substance of my work is travestis* and travestilidade, not because I am one and live this phenomenon, but because it is something substantially Latin American, from the global south, Brazilian and, above all, fluid despite its density—like air. In the hybrid places where identities mix, proliferate and come into unimaginable kinds of ‘devir,’ the travesti identity becomes a historical inevitability of a transgression that the white and cisgender humanism revokes. So, we face the challenge of translating our existences.

In some non-Western cultures, travesti is not about gender, but about another social organization that perhaps does not even cut through the realms of identity. Xica Manicongo, for example, mostly known for being the first travesti who was killed for her gender identity in 16thcentury Brazil, must be named and recognized for her own ancestral and temporal language and etymology. After all, the process of decolonizing the history of gender requires an understanding of the fact that neither Xica Manicongo nor the contemporary travesti identity corresponds to this history. Instead, they were, and still are, seeds of what is supposed to flowerin both the present and future times.

Of the four elements, air is also the main condition of being alive and being alive is the main condition to which I must be attentive. This rule I did not invent, but there are forces and knowledge that could only have emerged from the fact that I was subjected to them. To recite another great artist friend and clinical psychologist, Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro: “If I asked, I would breathe to do it. To breathe is to feel, and as long as I blow I'll stay alive. When I die, it won't be the end if you keep making wind in my life.”

Luana Vitra

JCdS: Could you define memory and how the memories of your childhood inform your practice?

Luana Vitra: In me, the movement of forgetting feels stronger than that of remembering. When I have no space in my mind, my body creates that space, "to fit more, I shed for nothing, I shed for no reason" (from the poem “Rios” by Viviane Mosé). Binding details of certain events remain in my body, and they are in constant need of revision. Memory for me is a careful selection of what cannot be forgotten within my body; it is a precision curve consecrated by forgetfulness.

My memories also connect to poetry and stories. My mother is a pedagogue and her teaching methodology is through poetry; she always writes a poem to introduce a new subject to her students. When I was a child, she made me memorize some of her poems. I started to deconstruct them when I was about 6 years old. By 9, I was using this language to understand life lessons. I had a friend at school who always came to classes with bruises on her body. This moment reminded me of the verses of a specific poem, and those words helped me understand that I needed to ask my mother to pay attention to my friend’s family. My mother made poetry my alphabet and way of seeing the world. She taught me a way to understand the present through metaphor, rhyme and beauty. Always diving into the instant, she taught me to be a bodyin the now. My father, on the other hand, is a body that stores the past. He remembers very old stories about our family. I really feel him as a guardian that protects the memory of what cannot be forgotten. My father always reminds me of the rebellion, the stubbornness, the consciousness and consistency of the gestures of those who preceded me.

I believe that my work is born from the meeting of these two forces. The stories that my father tells me are the birthplace of many of my works. I approach these memories by asking myself what image and shape they gain in a present dimension. Metaphor and poetry are formats I useto digest these memories. In the images, I reaffirm the weight of these facts. I feel that I live within a gravity cradle. I manufacture a lightness that allows me to inhabit the weight and understand of what it is telling me. When my body anchors, and in this alliance with the earth, I find my ancestors again. I am anchored by the weight of iron, a material that permeates the whole history of my family.

In my childhood, I remember always playing with pieces of ruined things. A few years ago, a friend dreamed that she was watching me from an aerial perspective; she saw me in the middle of a destroyed place, stacking fragments—"building the ruin," in her words. I think through this sort of activity is how I learned to sort my time. I construct from ruins, an exercise of seeing and perceiving through things undone. I work with iron. Not through iron, but through the land, the forest. I move from rust, which is the iron's desire to return to earth.

JCdS: And scent, could you describe the smells of your childhood?

LV: I haven't thought about the smells of my childhood in a long time. I closed my eyes to try to remember and some came to me. I remembered the smell of my mother's belly. When I was a child, while she braided my hair, I would rest my forehead on her belly. I have a lot of hair, so it took a long time to braid everything—about 4 hours. I remember breathing in the smell of her belly in the process.

My father is a carpenter. I remember that every day he arrived carrying the smell of a different wood. Sometimes, I liked a certain smell and asked which wood it was. I don't know how to identify many woods by sight, but the smells are very familiar to me. I remember the smell of them in contact with the iron in the moments when my father sharpened his tools.

I also remember the smell of earth that was left after my grandmother watered all the plants in the yard. After she watered everything, she would sit on the stairs and "warm up the sun," as she said. When I look back on my childhood, I see that the most present smell is that of the earth.

JCdS: What did you learn from your mother and other people in your life about protection? How do you plan to protect yourself in the future?

LV: With my mother I learned protection through affection, the network of friendships, care and love.She always offered me tender protection and she was a constant companion, knowing how to be present even when absent. With my father, I learned protection through observation and strategy. When I was a child, my father taught my brother and me how to work trapping. He taught my brother more about it because, culturally, trapping is always taught to men. But, I have always observed the way my father dealt with everyday issues. My parents’ different ways of being and reasoning were their individual guides for protection and survival.

I am currently developing research that builds on these teachings—the things I learned by observing the way my father acts and plans. For example, understanding trapping as a legacy that starts from my Afro-indigenous ancestry, I want to think about how I could develop a choreography and a self-defense plan based on this knowledge. I want to create traps for what threatens me today. I understand the trap as a muscular body on the prowl. Waiting for the prey triggers muscle tension; when the prey is captured, the muscles relax. I am currently studying my own muscles and other aspects that connect me to the structure of physical traps. But I also understand that I am not a trap created for annihilation, just as my ancestors were not made for that purpose. The traps that I create operate as protection, as they do in Capoeira Angola, a foot always a millimeter from the other's body. The foot never touches the other; it is just a warning that it could if it needs to. I have also developed ideas of protection within the field of visual arts, in dance and in my daily life. I know that my body is a trap and I believe that many gestures are inherited. I intend to protect myself in the future by studying these gestures.

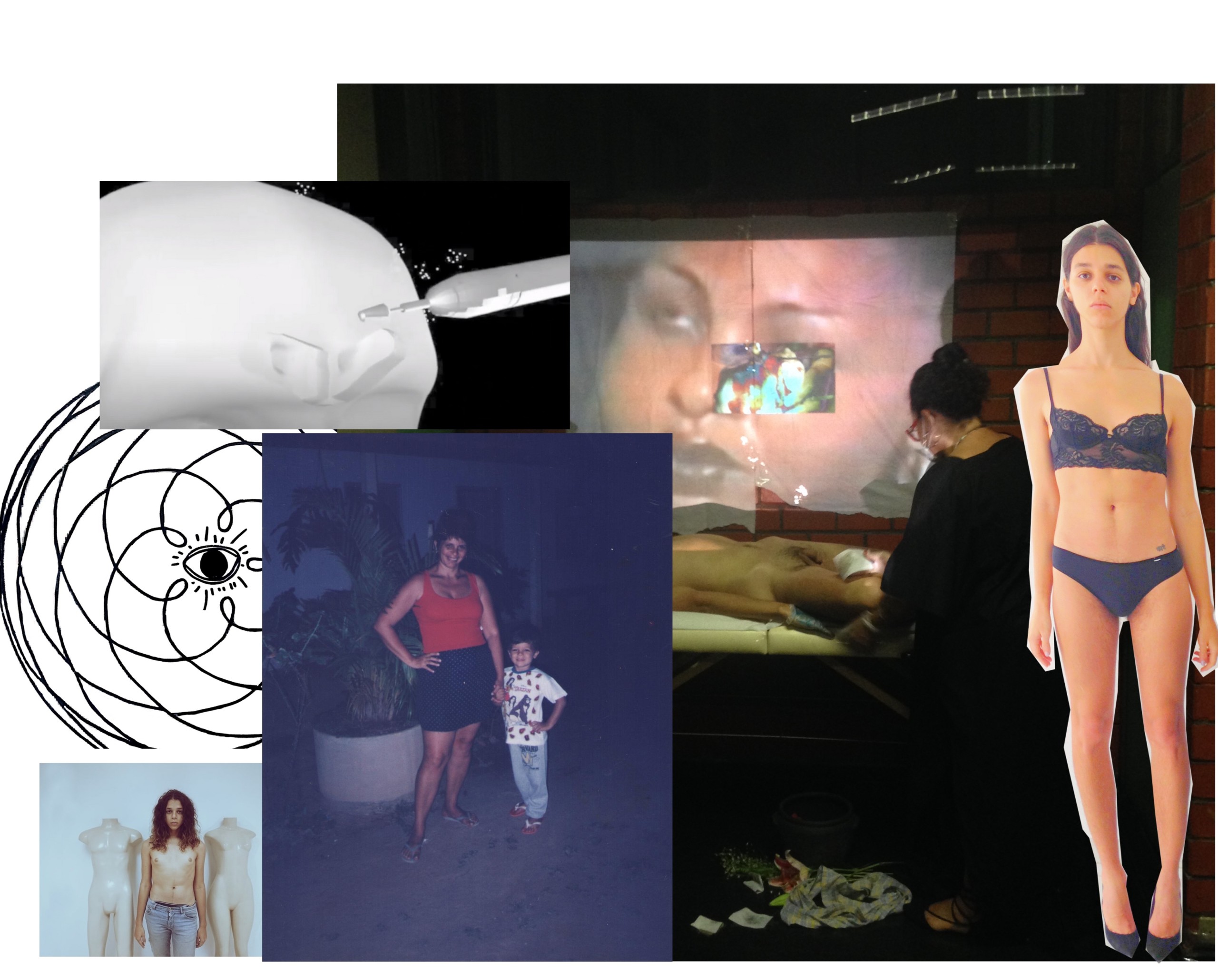

Giorgia Narciso

JCdS: What senses do you feel you are most activated through your work and how?

Giorgia Narciso: I like to look at my memories which, in some way, also relate to collective memories of people with life crossings similar to mine; social class, deviation from the heteronormative cisgender gender ideology, femininity as a curse and liberation at the same time; desire for acceptance and love; a cure for the cowardly violence inflicted on LGBTQIA+ people. I like to create personal experiences and exchanges with my community from memory. This is usually the starting point, and I use signs and artistic languages to express myself, whether through performance, video, writing, illustrations and prints, etc.

One of the languages that I like the most is performance, because it places me in a state of absolute presence, an exchange of energy and contact with all the senses; in general, when I create a performance I imagine a narrative and choose signs to compose with, such as the romantic songs that I heard my mother listen to when I was a child. I use the power of an outfit or the smell of a lily or the estradiol in the cauldron, the sound of the hairs being pulled out and exposed on the tapes with wax, the way it hurts.

Screen printing is also an interesting way, where all of the senses multiply on fabric, skin, paper. But nothing beats text and image: the power that the narrative has to transport and transform us. I always try to work with semiotics. Nothing has shaped me more as a person, apart from my individual experiences, like books and films. Words and images.

JCdS: How would you describe your most influential and inspirational relationships?

GN: Passion and intentions. I like passion because it can overwhelm the senses and is often the first step towards love. I am taken with personal histories. Mainly the stories and histories of other transvestites and trans people. Sometimes I get hurt in those dynamics, but I think that’s part of it. I tend to romanticize, but people are not narratives. I am also inspired by people from all walks of life; pop idols, great artists—Roberta Close, La Veneno, Cláudia Wonder, Ventura Profana, Frida Kahlo, Yoko Ono, Machado de Assis, García Márquez, Tina Turner, a lot—but I think I'm mainly inspired by people close to me; the women in my family, my friends, their affections.

JCdS: When do you feel most like yourself? What does loving yourself feel like?

GN: I am most myself when I feel belonging and I feel wanted. I hate the feeling of trying to fit into spaces. Being with friends and loved ones, in general, makes me very happy. My love relationship with myself is an ongoing effort to welcome and transform my shadows and believe in my potential and qualities. Sometimes it's difficult and I blame myself too much. But the moments I manage to accept myself are when I also feel that I love myself despite the regrets, and I manage not to care so much about what others may think about me.

*Travesti = Identidade trans feminina latina/brasileira (Brazilian trans woman identity).

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.