The friendship of Claude Arpels and George Balanchine has gone down in history as one of the more fortuitous encounters between the worlds of fine jewelry and dance.

The heir to the Van Cleef & Arpels empire and the choreographer met in 1961. Arpels had grown up frequenting the Paris Opera with his uncle Louis, a champion of ballet who helped make the ballerina clip a Van Cleef & Arpels signature; the Russian-born Balanchine was by then a renowned figure stateside, having established the New York City Ballet in 1948 and given the postwar public a treasure trove of now-seminal works. Six years after meeting Arpels, Balanchine would cement their bond—and his reverence for his friend’s artistry—with Jewels, a plotless ballet divided into three acts: Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds.

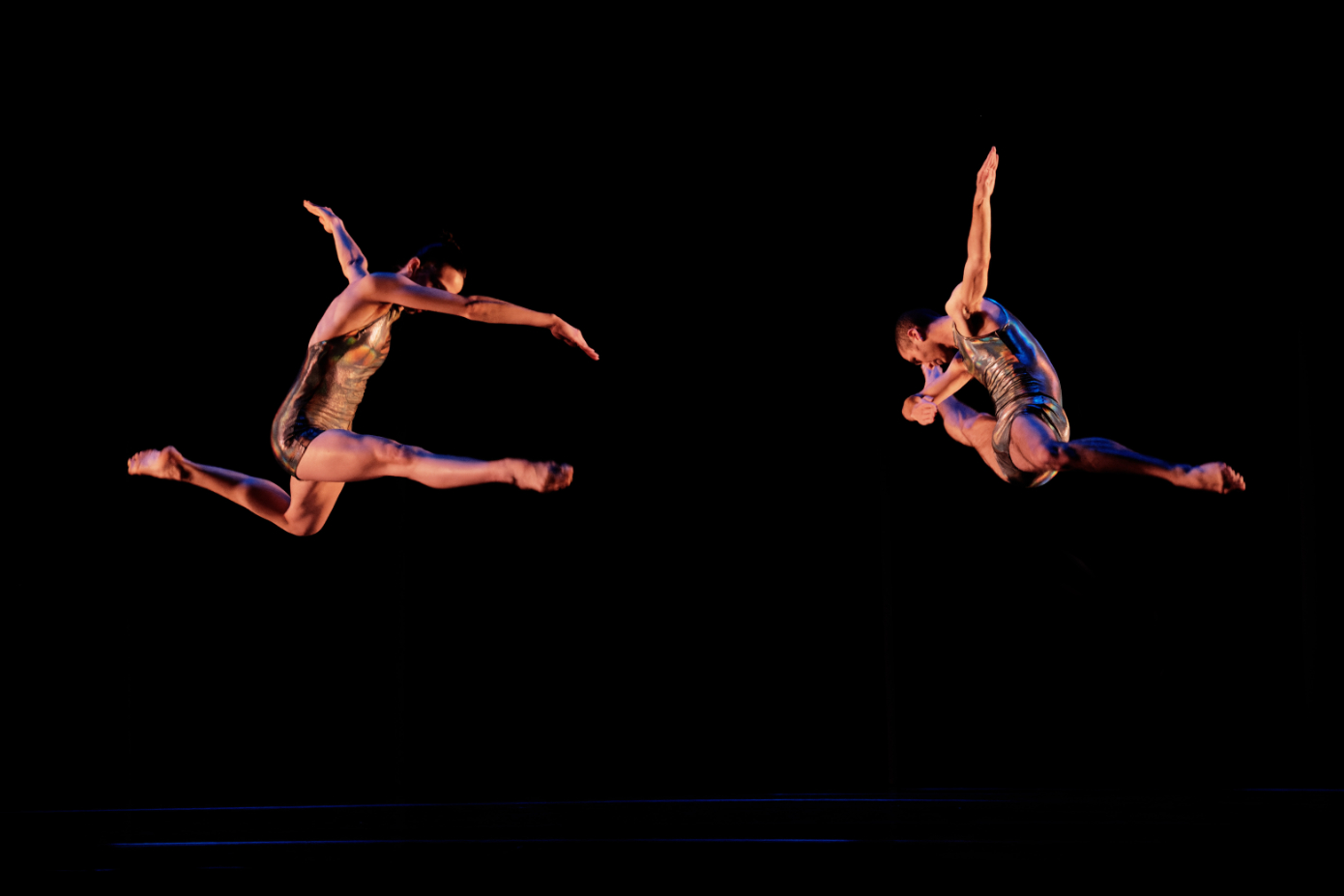

Reflections: A Triptych, commissioned by the jewelry house from leading choreographer Benjamin Millepied and similarly inspired by precious stones, follows in these storied footsteps. The trio of works, set to scores by Philip Glass and David Lang and punctuated by visuals from artists Liam Gillick and Barbara Kruger, is at the center of Van Cleef & Arpels’s second New York edition of Dance Reflections. (Reflections will be performed in its entirety in New York for the first time on the occasion.) Running through March 21, the festival brings 15 other dances—both canonical and ultra-contemporary—to the city, as well as over 20 workshops for professionals and enthusiasts alike.

The festivities kick off this weekend with a one-two punch that bridges three decades of creation. The Lyon Opera Ballet will perform Merce Cunningham’s 1999 Biped, which he once compared to “switching channels on the TV,” and rising Greek auteur Christos Papadopoulos’s 2023 Mycelium at New York City Center. More Merce follows next week, when the Trisha Brown Dance Company and Merce Cunningham Trust stage the late legend’s 1977 Travelogue alongside Brown’s 1983 Set and Reset. Both dances pay homage to Robert Rauschenberg, whose centenary is being honored this year; watch out for the artist’s distinctive silkscreened costumes in Set and Reset and his sculptural composition of wooden chairs, white platforms, and bike wheels in Travelogue.

The global 21st century is also well represented at Dance Reflections. Soa Ratsifandrihana mingles popping, the Madison, and dances from her native Madagascar at New York Live Arts, where the Franco-Algerian choreographer Nacera Belaza also stages her hypnotic La Nuée, inspired by attending a powwow outside of Minneapolis. Belgian mainstay Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker rallies 13 performers at NYU Skirball in an ode to walking, while Alessandro Sciarroni excavates the polka chinata, a 20th-century Italian courtship ritual that literally brings men to their knees. The offerings are sweeping, yet the program somehow maintains the intimate feeling of a young Arpels visiting the ballet or slinking around to the stage door to meet a rising choreographer.

As the festival kicks off in earnest, we sat down with Sciarroni, Belaza, De Keersmaeker, and Serge Laurent, Van Cleef’s director of dance and culture, to speak about bringing these works to life.

How do you develop your choreographic “language,” and what dictates when a gesture, step, or pattern feels complete?

Nacera Belaza: I developed my choreographic language through a long process of stripping movement down, seeking to reach its essential core. I do not build by accumulating gestures, but by working through subtraction: I repeat, refine, and narrow the movement until it becomes necessary. A pattern feels complete to me not when it responds to an external form or an aesthetic intention, but when it asserts itself as an inner certainty. Repetition plays an essential role: It is not used to make the movement evolve, but to deepen it, to reveal its density and its sensorial charge.

For me, choreography is above all a form of listening: listening to the body, to silence, and to the infinitesimal shifts that occur. Movement is a material that can be sculpted endlessly; each performance is only a renewed attempt to reach a point of balance that remains fragile and unstable.

Alessandro Sciarroni: Although the idea for a work always arises from an individual intuition, the creative processes involve various people and figures: first and foremost, the performers, with whom, during the rehearsals, we search for something, even though we often have no idea what. The production usually culminates with its dramaturgical writing. Once the dramaturgy is finalized, defining its choreographic translation is a fairly rapid process.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker: Music was my first partner. I have made nearly 70 choreographies over 45 years, and I’ve worked with music from many different centuries. In the last decade, art has become increasingly important as a source of inspiration to develop my vocabulary and language, as well as literature. There is, of course, always a very close working relationship with the dancers. As there is not a codified language like there is in ballet, with its frameworks of time and space, I’ve developed [one] with the dancers, trying to establish something in which they can find themselves in their body. Sometimes it’s patterns, geometry, mathematical proportions, observations of animals, or social structures. But overall, music has been, until recently, my partner and first source to develop that language.

Dance Reflections places your work alongside a spectrum of histories and performances. Does presenting your piece in this context reshape the way you think about its relationship to others?

Belaza: Placing my work within the context of Dance Reflections does not alter the nature of the piece itself, but it does shift the way it may be perceived. My works are not constructed in direct dialogue with history or with other forms, but arise from an inner necessity. Yet presenting them alongside other gestures, other temporalities, and other choreographic writings creates a field of resonances that operates without intention. This context brings to light correspondences that I do not seek to produce, but which I welcome as perceptual phenomena, belonging more to the experience of the viewer than to any explicit desire for dialogue.

Presenting a piece within such a framework is a reminder that each work exists both autonomously and within a broader fabric of presences and memories. It does not redefine my relationship to other works, but it heightens our awareness of the ways in which a piece may be traversed by histories and resonances that extend beyond it.

Serge Laurent: I believe it is essential to emphasize that today’s art, and of course contemporary dance, is the result of a history and evolution of the arts that has never ceased. Bringing together works from the past with recent pieces reflects this history. Thus, following the thread of history is certainly a good way to approach contemporary art. Presenting emblematic works alongside very diverse contemporary pieces undoubtedly allows us to showcase the richness of creation. The festival is characterized not only by its programming, but also by its desire to tell the story of dance and to develop awareness of it.

From where within you does your work awaken? Personal experience, education, cultural influence—a combination?

Sciarroni: My work always starts with an intuition. It could be a book, a photo, a dance, or a pre-existing practice. The moment I ask myself if I could work on that object, it usually means a new project is being born.

Belaza: My work awakens from an inner place where lived experience, imagination, and the unconscious intertwine. It does not arise directly from a personal narrative, nor from transmitted knowledge or an identifiable cultural influence, even though these dimensions inevitably inhabit me. They operate in an underground way, like layers, without ever becoming explicit material. What initiates the work is above all an intimate necessity, an intuition—sometimes difficult to name—which I often grasp through my relationship with nature.

Education, cultural references, and lived experiences shape this inner terrain, but they do not dictate the gesture. They are present in negative space, like a diffuse memory that nourishes listening and availability. For me, dance originates in this space of tension between what has shaped me and the unknown toward which I aspire. It is a place where the intimate detaches itself from the anecdotal to reach a more essential, almost impersonal form, capable of resonating beyond individual history.

What context would you like audiences to be aware of as they take in your performance for the first time?

Sciarroni: I always prefer that spectators come to the theater unprepared. When I compose, I always address an imaginary spectator who happens to be passing by chance by the studio where we are rehearsing.

Belaza: What matters above all is the availability of the gaze and of listening, more than knowledge of a framework or an intention. If there is a context to be shared, it relates more to the temporality of the work: an invitation to slow down and to become available. The piece asks to be moved through without immediately searching for meaning, allowing the body to perceive before the intellect. I would like the viewer to know that dance is not conceived here as a narration or a demonstration, but as a field of intensities and imagination. It is a space to be inhabited rather than interpreted, where each person can experience a deep letting go.

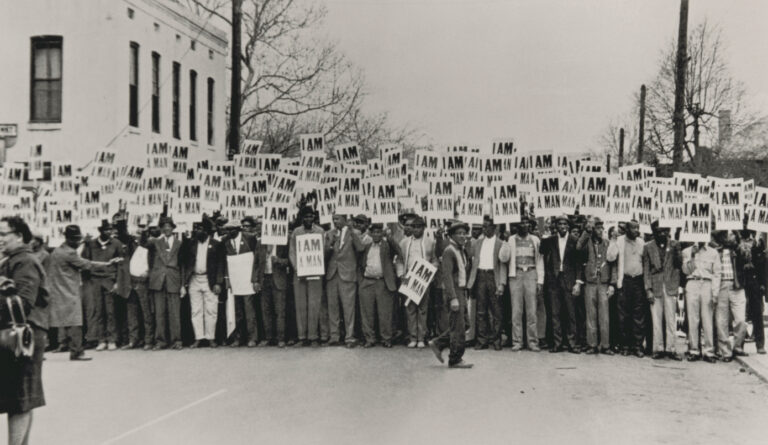

De Keersmaeker: It’s nice, actually—Dance Reflections—because it has something about mirrors. Reflecting is about the image, or the way we see ourselves. What’s happening in the world right now raises a lot of questions. It raises questions about what hope there is for the future. There is extreme violence on many levels. I can only have the modest hope that there can be some kind of healing aspect created, by introducing this liminal space.

The festival spans museums, opera houses, and newly activated spaces like the New York Center for Creativity & Dance. How does the site shape the way choreography is read?

Laurent: When presenting a work, the choice of venue is essential. The identity of the place, its history, its artistic line, its audience can, of course, determine the choice of works presented. The diversity of venues we collaborate with in New York allows for formats and choreographic approaches that are very varied. Artists appropriate and reinvent the space. Some works need to be viewed in a theater, while others establish a close relationship with the audience or are integrated into the architecture, such as at the Guggenheim, for example. These different ways of presenting dance are also what make it rich and beautiful. The festival is a platform for discovering dance, but it is also a place for transmission and education. That is why this year we chose to organize workshops at the New York Center for Creativity & Dance for everyone. A way to present dance differently to each person, in practicing it.

What is the most impactful takeaway you hope both seasoned viewers and newcomers walk away with?

Sciarroni: I am not particularly interested in what a spectator takes home with them after the show. However, it is very important that the fruition of the work is an experience for the viewer. This happens when, as spectators, we recognize something of ourselves in what we are observing. Especially when what we are watching initially seems to bear no resemblance to us at all.

Belaza: I often say that I do not create for the eye, but for a deeper memory, a more unconscious place. Indeed, the small amount that the viewer thinks they perceive during the performance is in reality only a tiny fraction of what truly permeates them. What remains of a piece is often mysterious—a fleeting image, a feeling, a disturbance—that lingers and resonates long after, for a very long time. In fact, I believe that the strength of a work is measured by the traces it leaves in our lives.

De Keersmaeker: Dance is what it is. It stands for itself. I’m very happy that we can come back to NYU Skirball and to New York. I’ve always had a very strong link to this city because I studied there, and made my very first pieces there. Especially in these turbulent times, let’s aim for the best.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Julie Delpy Knows She Might Be More Famous If She Were Willing to Compromise. She’s Not.

Our Critics Have Your February Guide to Art on the Upper East Side

Move Over, Hysterical Realism: Debut Novelist Madeline Cash Is Inventing a New Microgenre

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?