In case you haven’t heard: Mary Boone is back.

The renowned gallerist, who shuttered her eponymous gallery in 2019, has returned to the New York art scene as a collaborator on “Uptown/Downtown” at Lévy Gorvy Dayan. On view through Dec. 13, the show deftly tells the story of the city’s art world of the 1980s through works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Richard Prince, and Cindy Sherman, among others. The scene, Boone says, represented a time of “optimism”: an atmospheric sense of possibility that allowed someone like her, a young woman who did not come from money or a notable family, to establish a successful gallery and keep that gallery running for 42 years. (She closed the business in 2019, after being sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison for tax evasion.)

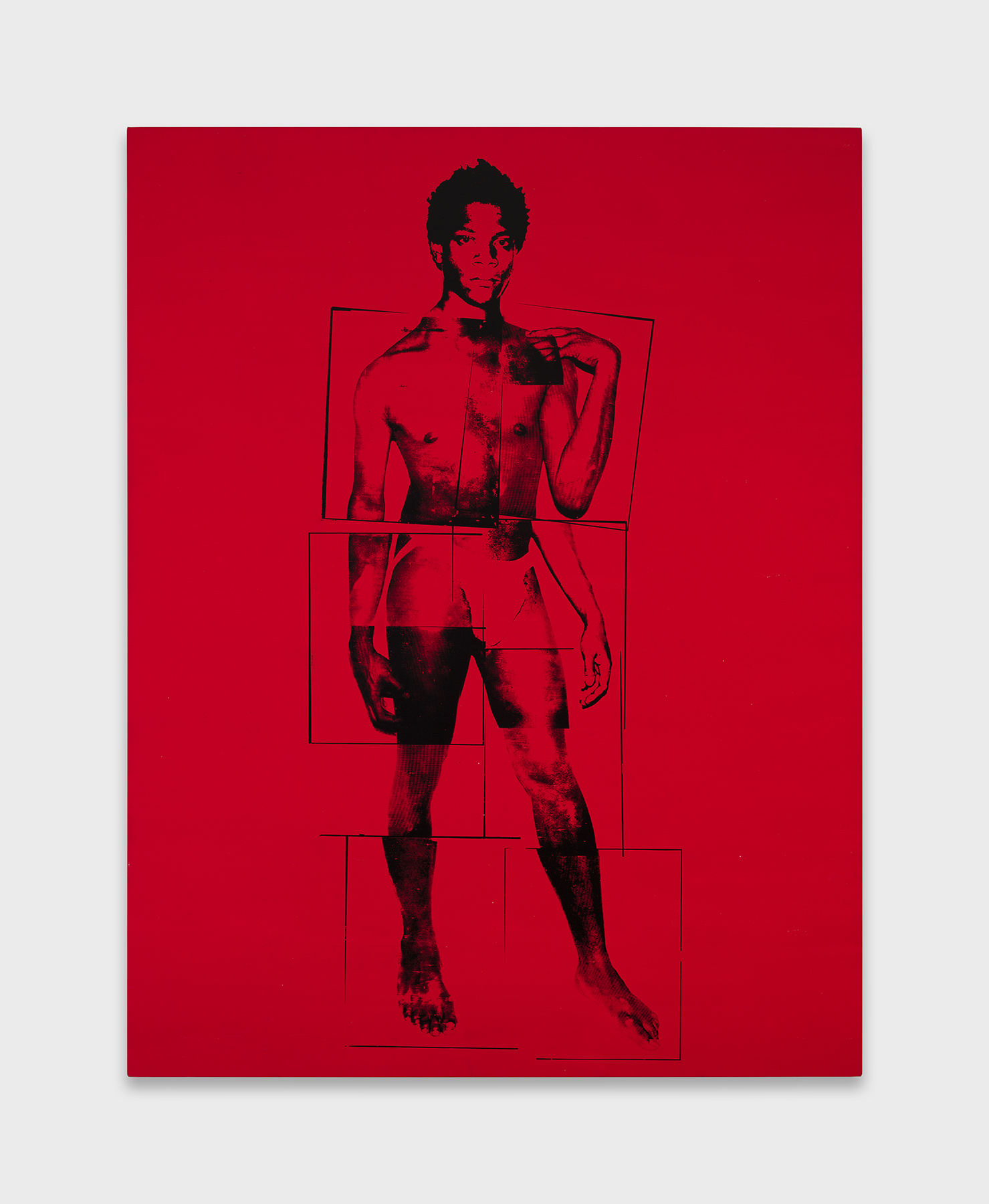

On a recent Monday afternoon, I sat down with Boone for a conversation about her comeback. Visitors bustled in and out, snapping pictures, posing in front of a punching bag by Basquiat that bears Boone’s name, and climbing the gallery’s curved staircase beneath Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (What Me Worry?), 1987.

“Uptown/Downtown” is one of the best shows I’ve seen in a long time—not only because of the quality of the storytelling, but also because of the conversation it’s been generating among the collector class. A new generation is getting a chance to see works that may have been in storage for decades.

And Boone is as dynamic as ever. As you’ll notice, we finish each other’s sentences throughout the conversation, getting carried away in our analysis of the art world then and now, both women who can’t help but be obsessed with this unwieldy, often disappointing, but never boring world that we occupy.

Other galleries, I’m sure, approached you to do something like this before. What made this time different?

They were more convincing.

I’m sure the people would love to know how.

It seemed like a natural fit. They were younger than me, but not that much younger. They had lived through the ’80s, even though they weren’t maybe immersed in it. At least Brett [Gorvy, one of the gallery’s three principals], I think did. I love the space [Lévy Gorvy Dayan]. And they are really hard workers, so it just seemed like a more natural fit.

Why do you think the art of the ’80s is being re-contextualized now?

A lot of people are excavating the ’80s because they’re realizing that there was a lot that happened there for us to examine.

Thinking about the ‘80s and the market boom during that time, it’s kind of a similar market boom that we had in the early 2020s.

I don’t know that it was a market boom as much as it just looked very different by comparison. We came out of a depression. Being here in the ’70s was very… I mean, the city was poverty-stricken.

Yeah, SoHo was not the safest place to live.

No place was. There was a lot of crime. And what you saw was a new optimism. That’s what made the ’80s so exciting.

And then do you think that that optimism spurred the decisions you made and the shows that you did?

The optimism allowed someone like me to have a gallery. I was a woman. I didn’t come from money. There was really no nepotism. I didn’t have a family in the art world. In the ’80s, it was possible to do things like that.

As a woman in the art world that definitely has ins, I think there’s still an element of that being super incredible when a woman gets [there] on her own.

Because women are expected to act like men if they want to be successful. And it was learning that that didn’t have to be the case.

I was talking to a friend the other day, and I said, “If I could see one show on the East Coast, I would see this show. If I could see one show on the West Coast, I would see Derek Fordjour’s show at [David] Kordansky.” It’s because when I look at this show, it might be a reflection on the past, but it actually is an invigoration of what the art world can look like, and how successful it can be, and how…

Possible everything is. We’re in a time or a mindset that’s very negative, I think. And this tries to go against that. Brett likes to say, “This is a love letter to New York…”

There are all these young artists that are in conversation with each other now that are maybe being overlooked because everyone’s trying to find the one next star. But if you look at this show, it’s a collective [of young artists] that influenced each other.

To me, every artist in this show is a star.

I’d be curious to hear your perspective on the gallery landscape now because there is such a conversation of “the Lower East Side galleries are this, and the Chelsea galleries are this, and the Uptown galleries are this.”

It’s not really about location. What really needs to happen more is communication. Artists need to have a place to hang out, where they can cohabitate. That’s the biggest thing that’s missing from the art world. The AbEx [Abstract Expressionist Movement] had the Cedar [Tavern], and we had Max’s Kansas City. And then later came the Odeon. Computers took away even more of the interaction between artists.

Also, the gentrification of New York. In Just Kids, Patti Smith was like, “We would go to the Odeon because Warhol was there, but at the time we could get a soda pop and just sit.” Nowadays, that doesn’t exist. Artists have been priced out of Manhattan. And I agree with you that the Internet has probably taken away a lot of that connectivity. But in this show, you’re not only bringing together artists but also the collectors who have really championed them, who are loaning these works. They’re in conversation with each other, too.

I remember Eli Broad used to love going to Jean-Michel [Basquiat]’s studio because he was fascinated by the fact that Jean-Michel was barefoot all the time. He says, “Imagine that. Can you imagine going to work and you’re barefoot?” There are a lot of connections between artists and collectors.

What I think is cool with this show is that the collectors get to come in here and be like, “Oh, you, too, appreciate this.” Even the few collectors that I know who have contributed to this show have called each other and been like, “Your work looks amazing in the show. It looks great next to mine.” A lot of the collectors that I know tend to keep their things private; half of the stuff is in storage. The fact that they have a stage again, and with all their peers, is really cool.

It’s nice having that reconnection.

Obviously, you’ve had a ton of life experiences, and I’m curious to know your perspective after re-experiencing the art world in its current state. What are your experiences of this generational shift, and how do you feel you were treated on your return back to this incredible, glorified show? And how do you feel the market operates differently now?

That’s about 20 questions.

I know. Let’s start with the first one.

I think that the thing that really changed New York was the pandemic. And in fact, 2020 to 2022 was probably the best [for] sales. Because people were staying at home and thinking about what they needed. A lot of galleries closed around that time, 2019 to 2024. But that’s been, I think, needed. Because there’s a… How can I explain this? There’s an organicity between how [long] things last. And usually we acknowledge it through decades. The ’60s, except for Jasper [Johns], all those artists are gone. The ’70s, a lot of those artists are gone. The ’80s, the artists are basically still here, but the thinking is different.

I’m curious about your perspective on the role of museums in all of this.

Well, museums have had funding cuts. They don’t have the access to be able to do big shows. You could never do a Jasper Johns painting show because the insurance alone is exorbitant.

They did a Jasper Johns at the Whitney [in 2021].

No, they’re prints. And that’s why they did the prints—because to do paintings, there’d be hundreds and hundreds…

Well, the Rothko show in Paris was crazy, but LVMH did that one.

That was funded by wealthy art supporters.

Which again begs the question of, do you feel like in the ’80s, it was as political?

I thought it was pretty real. It was egalitarian. The artists were not getting bought off by collectors. The thing I remember when I was doing the [Roy] Lichtenstein show, it was in May of 1991, and Leo [Castelli, who represented Lichtenstein] let me do the mirror paintings because he didn’t really like them. And I was hanging the show with Roy, and Roy said, “The only thing that I feel worried about with your generation is that they didn’t get a long enough time to develop.”

It’s true.

“My generation, you had to teach until you were 40. And these artists are making headlines in their 20s and 30s.” Well, now it’s like these people aren’t even out of school.

It’s actually swapped a little bit. It’s very hard to be an important artist at 20 now, and I think it’s hard for the collector to navigate which direction to go in.

I think it’s because they’re looking for the wrong things. They’re not looking for what they love.

Or they just don’t even know where to start. I don’t think there’s enough education to be like, “Hey, go to the museum. See what the museum is bringing into its collection at the $10,000 range. See what is fitting in the zeitgeist of what might be shown in five years from now.” I got lucky because I grew up with art, and I grew up with a trained eye, and I know the history of art. And I know where inspiration from Warhol comes from to the artists now. People say derivatives are bad but I look for some sort of through line because there’s so much content out there that I need to know that the person I’m investing in at this young age has legs. This show, why it’s so great, is because it has a storyline.

And it’s not just your kind of clichéd read on what happened. I think starting with Warhol as being the beginning of the ’80s, that was true. Andy really influenced these artists. And they influenced him, because he wasn’t really taken in by his own generation.

What you did here is really special. I hope that the public sees the possibilities and sees how this could easily come back together again with a whole different set of artists if people start taking the throughlines more seriously.

in your life?

in your life?