The first time I heard of the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles and her Manifesto for Maintenance Art, I was cooking dinner with a baby on my hip and yelling to my two stepkids in the living room for help setting the table. A friend stopped by to grab some keys, and I apologized for my chaotic demeanor. “Have you read the Maintenance Art Manifesto?” he asked. Then he texted me a link to Ukeles’s document, written in 1969. In it, she declared: “I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I ‘do’ Art. Now, I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art. My working will be the work.” I thought, Sign me up.

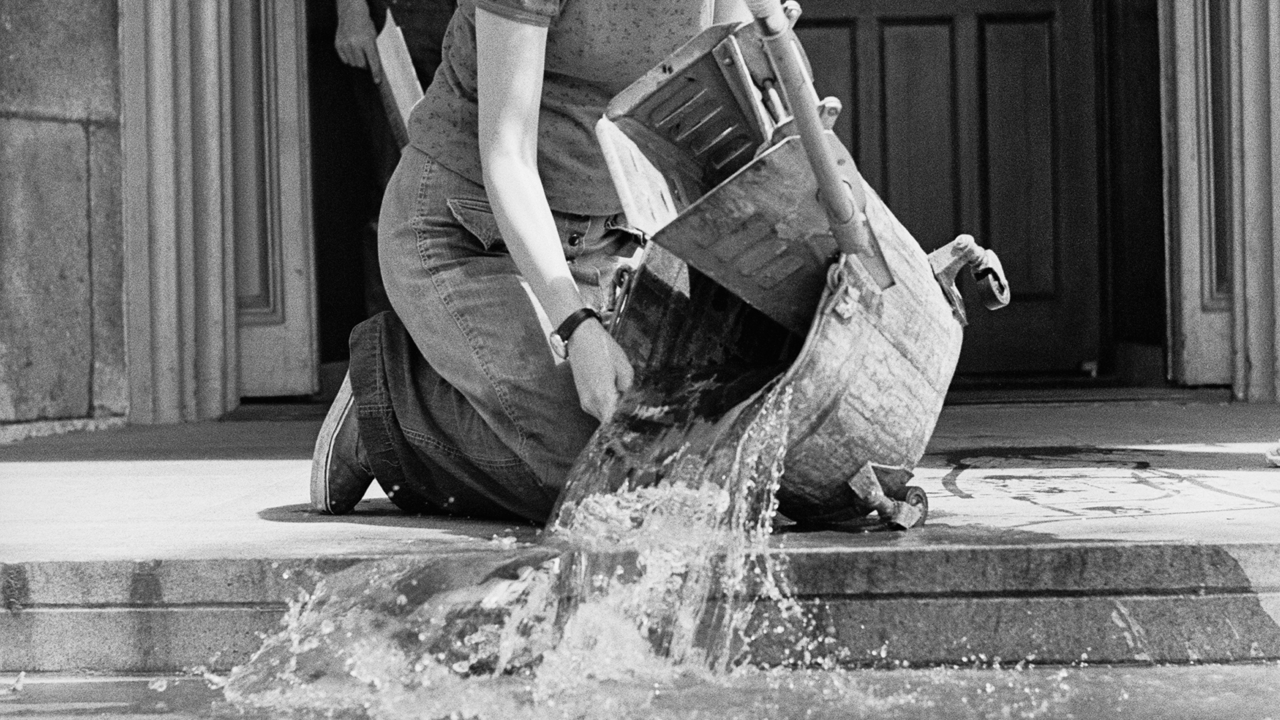

I’m not the first to be inspired by Ukeles’s Manifesto for Maintenance Art, today a foundational text in many contemporary art and feminist circles. But what’s more remarkable than the punk bravado of its vision is the way Ukeles put it into practice. Since 1977, she has been the official, unsalaried artist-in-residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation, a role she created for herself when the city, on the brink of bankruptcy, was slashing the department’s funding. For one of her most famous projects, Touch Sanitation, begun in 1979, she thanked and shook hands with all 8,500 of the city’s sanitation workers. Today, she continues to shape plans for Freshkills Park, scheduled to open on Staten Island in 2036 where there was formerly a landfill—once Ukeles’s stomping grounds.

In 2016, the Queens Museum in New York mounted a retrospective of Ukeles’s prolific career (“Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art”), and it grabbed the attention of filmmaker Toby Perl Freilich. “She worked in so many different media, but the real raw material for her was the human connection,” says Freilich, who approached Ukeles and asked if she could film her. Initially wary of Freilich’s interest, Ukeles was impressed when the director offered to document the artist while she curated her archives for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. “I was very moved that she was interested in the nitty-gritty of an artist casting a long look at what should be saved,” says Ukeles, now 85.

Over time, with Ukeles’s cooperation, Freilich’s project expanded to include footage from the artist’s early life and work, as well as interviews with art historians, curators, and her family. The resulting portrait, Maintenance Artist, illuminates Ukeles’s iconoclastic influence on the definition of art itself. Ahead of its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, I spoke with Freilich, who lives in New York, and Ukeles, who now splits her time between Jerusalem and New York, about the film’s development, the ambiguous state of feminism, and the process of social change.

Rose Courteau: Toby, what drew you to Ukeles’s work?

Toby Perl Freilich: I’d always been sort of intrigued by conceptual art, because it’s an art form that many find inaccessible. I wanted to demystify a work of conceptual art. Mierle’s work is both complex and accessible. I thought, I get an hour and a half to basically explain an artist’s process.

Courteau: Mierle, the footage of you going through your archives is a relatable scene for many people, whether or not they consider themselves artists. What was happening during that time?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles: It was very emotional. I make public art, and public art has a lot of paper. You have to go to a lot of meetings, you have to explain yourself, and apply for this grant and that grant. My role at the Sanitation Department of New York was given in a weird circumstance. I was official but unsalaried. I didn’t have a contract saying, “This is your office.” I was moved several times from one building to another. [At one point, the department] gave me three large rooms that became a big office with storage, and I was there for quite a few years. Then there were changes of administration. I was told to consolidate my office from the three great big offices to one office on the 11th floor at 44 Beaver Street, which I still have.

I was wondering, Where’s all this stuff going to go? At the same time, some people came from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art and said they wanted to keep my papers. So, I began the saga of consolidation. Toby walked into this situation.

Freilich: This was August 2017, but I didn’t have any money. I talked with a friend of mine who said, “How about I give you $5,000?” I had a wonderful director of photography, Vanessa Carr, and I just filmed whatever I could for $5,000. Mierle had very well-organized video and audio materials sitting in a metal cabinet. She took another leap of faith and allowed me to select some that I could digitize. Raw material from the Touch Sanitation performance became the core of the digitized material.

Courteau: There are so many different angles to Mierle’s story. What did you find was the most compelling pitch when you were gathering funders?

Freilich: Raising money was torturous. I got a little here, a little there. The hook was that I wanted to make a film about an artist-in-residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation. The contradictory elements hooked people. Then I would rapidly switch to the manifesto and the notion that this work started as a sort of feminist cri de cœur. But it was much more than that.

A lot of women artists [in the 1960s and 1970s] were working on things like the objectification of the female body and were very central in their own performance work, stripping naked or whatever. It was very courageous and necessary, but what appeals to me about Mierle’s work is that she moved the needle from her own experience as the frustrated mother, housewife, and artist to consider that the world was full of people who took care of all of us, and that they weren’t the ones getting the glory. So the second pitch was: “Men create things and women keep the dust off the pure creation, and keeping the dust off could be an act of art.” That’s when people were reeled in, I think.

Courteau: Mierle, did you ever struggle as a woman while working in the Department of Sanitation?

Ukeles: I was treated very well. There’s a code of being polite in the department. The thing that made me pissed off was when someone would say, “People hate us. They think I’m their mother. They think I’m their maid.” They didn’t say, “Isn’t that terrible to think about mothers and maids like that?” There was disappointment when I heard that, but I found that disappointment in a whole bunch of other people, not a few sanitation workers who would be honest and tell me what was going on inside. Highly educated men would say things where I thought, Oh my God, that’s the same thing. They really think I’m in a different class.

Courteau: One question that emerges from Mierle’s work is the chicken-and-egg question of: What do we need to change first, our minds or our material conditions?

Ukeles: My mother was born in the Ukraine, and her father left when she was 2. She didn’t see him again until she was 12, when they rebuilt the family in Kansas City, Missouri. She married my father, who also came from an immigrant family. He was a rabbi, and his first job was in Denver, Colorado. They left their families and built a life for themselves in Colorado. My mother was 22 and said, “I can’t live in a city that doesn’t have a professional symphony orchestra.” So what did she do? She joined a group of almost all women from all over Denver, and they raised money to build a professional symphony orchestra. She worked on that with no pay whatsoever, for her entire life. What is the connection to your question? It’s about doing it. You really do have to have a dream that you’re ready to fight for.

Freilich: You don’t have to hit most people over the head with a sledgehammer. Sometimes you just have to make them aware. And you can only do this person by person. One of the nice things about making a film is it can travel.

Courteau: What do you each think about mainstream feminism currently? I realize that’s an impossibly big question.

Ukeles: I don’t know. A lot of women at this point in time are able to have big careers as artists and they’re being paid attention to. That’s a thing of joy. Whether that benefits many, many women is hard to tell. Politically, we have the Roe v Wade situation. Come on. The fact that some guy said to you when you had your baby on your hip, “Hey, there’s someone out there talking about this stuff,” that’s very moving to me.

Freilich: There’s a conscious effort being made, in the art world at least, to hear women’s voices. But I think there’s also a backlash in the wider culture. The forces that want to keep men dominant in all fields are very powerful, whether they’re conscious or unconscious. It cuts across race and ethnicity and everything.

Courteau: How do you each think about progress? Do you think it occurs slowly or in jumps and starts?

Ukeles: I come from the ’60s, when there was a lot of belief in progress, that we’re all going to get better. I am walking around these days feeling not so great. Greed is running wild.

Freilich: One thing Mierle said in an interview that didn’t make it into the film, was that she grew up in Colorado. You would look out the window and see the mountains and the sunsets, and it gave you a sense of possibility. That made an impression on me because I grew up in a very different home, where the idea was to be safe and not rock the boat. I grew up in Jackson Heights, Queens. My parents were Holocaust survivors [from Poland]. Their whole families had been killed. My father was a deeply caring person. He worked as a book binder in a factory, but he’d come home and help my mother take care of the kids. He would wash dishes. He was not the traditional Jewish man that way. And to me, the message from my father was, you have to be a mensch. He wasn’t a feminist. He was just a human being who cared about his beloved family.

Courteau: What is your hope that people will take away from this film?

Freilich: Film is a hearts-and-minds medium. People are moved in different ways, but it’s important that they be moved. Some people will just be moved and never do anything. And some people might be moved towards self-consciousness—about their trash or their maintenance workers, or whatever it is.

The film itself was an act of preservation. All of that analog video material was sitting in a metal filing cabinet in Mierle’s office. It would have just degraded over time and become lost. Performance work is ephemeral, and many of those artists from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s did record their performance works.

Ukeles: I would hope that people will come away from the film thinking that you can do big things that aren’t just general, but actually face each individual person who’s involved. You can listen to them, but you can also do something. We can change. We can build an orchestra. We can always build.

in your life?

in your life?