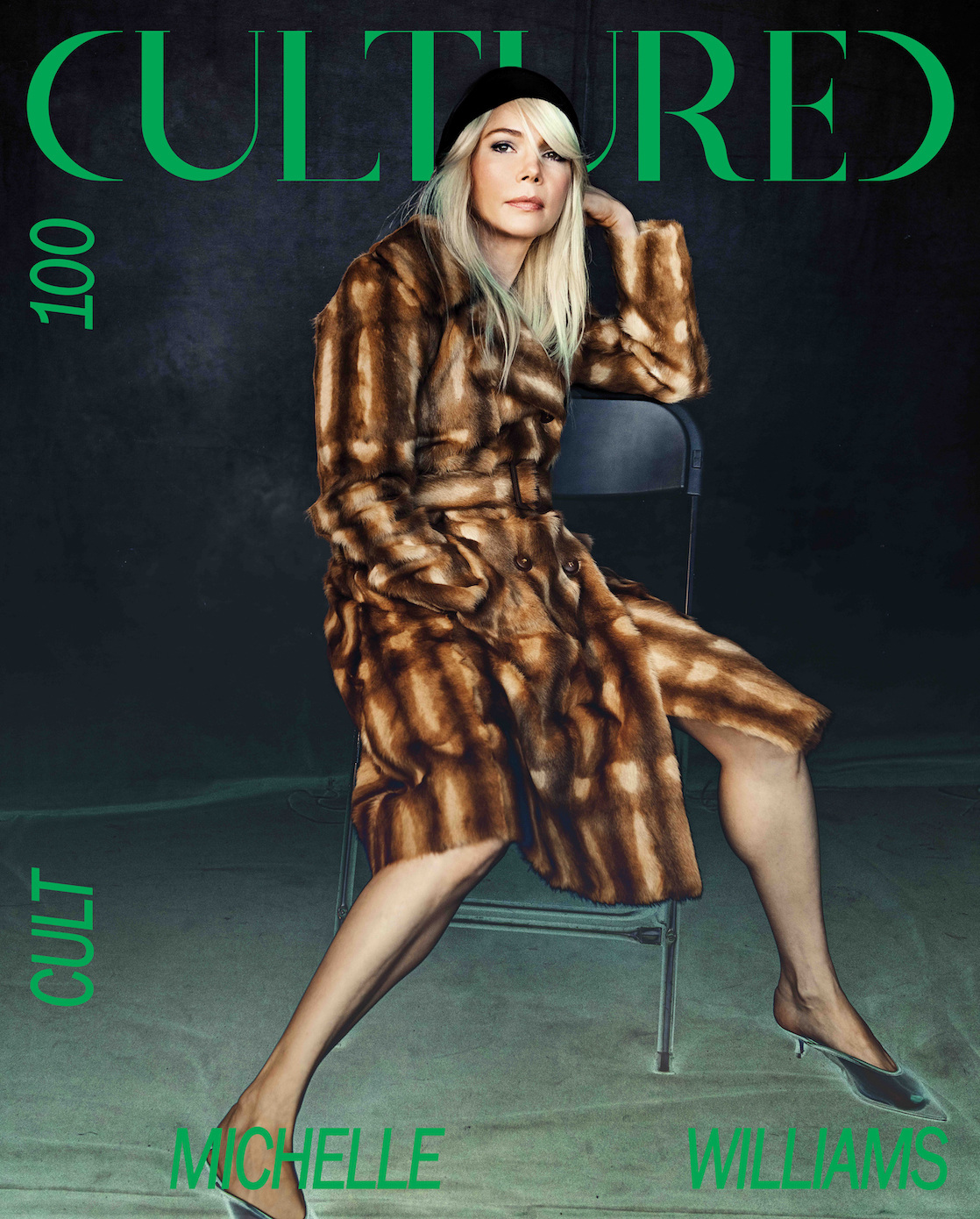

CULTURED’s second annual CULT100 issue spotlights 100 names across five generations who are shaping our culture in real time. Some members of the list are household names; others have been working behind the scenes to make possible the encounters that stop us in our tracks. They are all thinking big, sharing generously, and embodying courage. We hope their work makes you a little braver, too. Order your copy of the CULT100 issue here.

Michelle Williams’s face is mesmerizing to watch. It’s almost as if it were that of a newborn: reactive and curious, seeming to operate on its own timeline, stretching into a smile one second after you’d expect it to. The artistry of this face can make you forget that the rest of her body is doing a lot of the groundwork.

Remember her in Brokeback Mountain, confronting Heath Ledger’s tormented Ennis, her stiff, angry body braced against a kitchen sink? Or in My Week With Marilyn—for which she reworked her gait to better tap into the spirit of Monroe’s hips? For her Emmy-winning television role as Gwen Verdon in Fosse/Verdon, she played not only a dancer, but one learning a new style of movement over the span of 50 years.

That love of shape-shifting is what drew Williams to Dying for Sex, her second-ever limited series. In the dramedy, which she also produced, she plays Molly Kochan, a woman who receives a terminal diagnosis and leaves her husband, relying on her best friend Nikki (Jenny Slate) and her mother (Sissy Spacek) as her caretakers while seeking out the sexual experiences she’s spent her life yearning after. (The FX show is based on the podcast that the real Kochan recorded with her best friend, Nikki Boyer, before passing away in 2019.)

“I loved making something that was so about a body,” Williams told me earlier this spring. She was snacking on falafel from a takeout container, wearing a butter-yellow pullover sweater with her Twiggy-esque hair swept up under a crisp, white Yankees hat, eyes aimed out a window of the Brooklyn brownstone she shares with her husband, the Broadway director Thomas Kail, and her children. “A body is a host to so many experiences. But we carry so much shame about them.”

Williams was pregnant when she first read the Dying for Sex script. “I was taken with it in a way that happens very rarely for me,” she recalls. “But I was also scared of what it was going to lead me towards.” Reading any pilot script is already an exercise in the erotic—the thrill of committing wholeheartedly to something without knowing where it might lead—but most roles don’t call for multiple onscreen orgasms, let alone chemotherapy. (Unlike Anora, the Dying for Sex set did have an intimacy coordinator, and she taught Williams a few things. For example: “To give a convincing onscreen blow job, you suck your own thumb. It gives the proper, uh, tension,” she tells me. “Before that note, I looked like I was bobbing for apples.”)

Plus, Williams had a pregnancy to contend with. “[The other producers and I] talked about, like, ‘Could we do this with CGI?’” she remembers. “It seemed pretty ridiculous, trying to negotiate sex scenes with a six-month stomach.” Ultimately, the timing worked out: After Williams gave birth, she tracked the project down again. Filming began in the spring of last year.

Three decades into her career, people forget that Williams got her start on Baywatch and took off with Dawson’s Creek when she was 16. At that time, she was living alone in Burbank, having legally emancipated herself from her parents, ordering two pizzas a day for breakfast and dinner. She was playing a world-weary teen onscreen and a self-sufficient adult off of it—neither was her natural state. “I felt that if I had stopped and admitted that I didn’t know what I was doing then I would be really lost,” she told GQ in 2012. “The best thing to do was to just keep forging and to act like you were okay.”

When she wasn’t on set for Dawson’s, Williams was working hard to figure out what a natural state might look like—diving into independent projects that played against her doe-eyed teen-soap type, like the late-’90s teen satire Dick or Wim Wenders’s post-9/11 drama Land of Plenty. It was 2005’s Brokeback that laid bare her capacity to embody grief, bringing to life characters whose losses and desires infect them like a virus—a role she also unwittingly played in early-aughts tabloids, which hounded her after the death of her ex-partner, Ledger, in 2008.

Eventually, she harnessed these abilities, and the rest of her filmography is a record of her capacity to communicate years of accumulated suffering, longing, and connection well beyond the camera’s lens—Blue Valentine, Manchester by the Sea (both of which earned her Academy Award nods), and four awards-laden microbudget features by Kelly Reichardt. (She did a couple superhero films like many of her peers, but that’s easy to forget.)

Dying for Sex checks what have now become some quintessential Williams boxes—a character with a terminal illness is practically the physical epitome of aching, after all—but the series is also more responsive to cultural discourse than much of her indie or period drama fare. It’s peppered with cameos from comedians like Robby Hoffman and SNL’s Marcello Hernandez; it takes place in Brooklyn, where the apartments are beautiful and the clothes jewel-toned and hip (down to every last member of the hospital’s cancer recovery support group).

Perhaps most topical of all is the show’s belief in the transformative power of sexual liberation. Yet unlike some buzzy midlife crisis, grab-for-freedom escapades, Dying for Sex is still about dependence, relationships, and their many symptoms—just the ones that exist outside of marriage. “What’s so great about best friendship is that this person has witnessed it all; they’re holding exactly what you’re holding,” Williams reminds me. “There’s no explaining. You can just sit with it, and then go deeper and aid each other’s healing process.”

Perhaps this is what makes Williams an actor’s actor, the kind that tunnels past the bounds of a script, beyond the confines of a character and into their unspoken communion, their companions, their mortality, and their own body. After all, she seems to do the same in her own life. “The test of true friendship is the ability, desire, and willingness to tell the truth, as you see it, about the other person—because we are our own blind spots,” muses Williams, who has been known to bring her best friends to award shows instead of her partners. “When I told my friends, ‘I’m thinking about doing this show about a woman who gets a terminal diagnosis, leaves her husband, and turns to her best friend and says, “I want to die with you,” they were like, ‘Go. Please make that.’”

THE CULT100 QUESTIONNAIRE

What keeps you up at night?

My children.

What’s one book, work of art film that got you through an important moment in your life?

Can I say Faerie Tale Theatre?

Who do you call the most?

My husband.

If you could attribute your success to a single quality of yours, what would it be?

Maybe, possibly, my childhood in Montana.

Hair by Chris McMillan

Makeup by Angela Levin

Nails by Elle Gerstein for Essie

Production by Dionne Cochrane

Photography Assistance and Set Coordination by Jojo Roy

Photography Assistance by Kyle Thompson and Max D’Amico

Styling Assistance by Natalie Gilhool, Bonnie Robbins, and Chloe Jenkins

Production Assistance by Brittany Thompson and Thalia Saint-Lôt

Location: Pier 59 Studio

in your life?

in your life?