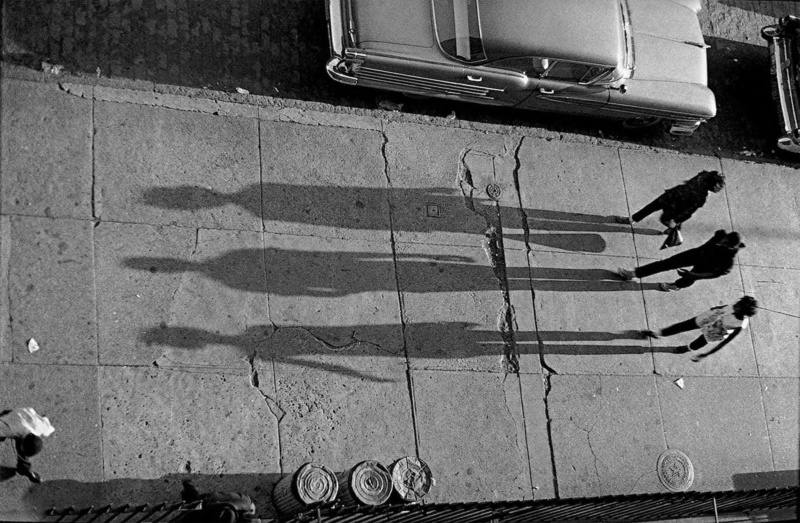

Adger Cowans has lived and made photographic history for more than 50 years, starting with his job as an assistant to Gordon Parks when he first arrived in New York in 1958. With a new book out and works on view in “Soul of Nation,” which heads to San Francisco’s de Young Museum this fall, the polymathic artist is among the forces who opened doors for the next generation, including Hank Willis Thomas, who is now leading the pack of today’s imagemakers. Willis Thomas took time out of preparing for “All Things Being Equal,” his solo show on view at the Portland Art Museum, to talk with Cowans about his life and work.

Hank Willis Thomas: I’ve always wondered how it felt as you were making your long and broad career. Did it feel like you were making history?

Adger Cowans: No, not in the beginning. There were no history books on photography in the ’50s, so photography wasn’t really considered an art. For me, the glory was being a photographer, like Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, guys like that. They were sort of my heroes. Of course, I really liked the prints of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. That was kind of the seed of what they called fine art.

HWT: Growing up in Ohio, how did you come into contact with Edward Weston?

AC: My teacher at Ohio University, Clarence H. White, was the son of Clarence H. White senior, who was an important photographer and knew Group f/64 with Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. I got to see actual prints by them because they were in his collection. When I came to New York in 1958 I worked with Gordon [Parks]. Nobody was talking about photography as art. Journalism was the route—to be a photojournalist—and Magnum was the big company for that. If you did anything else, they called it artsy-fartsy.

HWT: When did you start showing your work?

AC: I had my first one-man show at the Heliography Gallery in 1962. The Heliography Gallery included photographers like Paul Caponigro, Carl Chiarenza, Walter Chappell, Marie Cosindas, Scott Hyde and W. Eugene Smith. They were not commercial photographers; they were photographers who thought of photography as art. I related to that because at university, my teachers were concerned about your input in the photograph, as opposed to just taking a picture of something. So I had some foundation for a philosophy of personal expression.

HWT: That seems like an exciting time to be in New York, especially as a young creative person.

AC: We had big fights with the art guys, the painters, because they were saying that photography wasn’t art, it was craft. Photographers and painters and sculptors would get together and have these big discussions about whether photography was art or not. I think photography finally officially became art when Ansel Adams sold his picture Moonrise Over Hernandez for $1,500 and they put a photo of him on the cover of Time magazine. People thought it was crazy! Nobody had ever paid that much money for a photo.

HWT: I saw that photograph in someone’s house recently, an original print, and no one who was born in the past 25–30 years can really understand how incredible a feat it was to not only make that picture, but to make that print the way Ansel Adams did. Now there isn’t the same stigma around the idea of photography as craft as there was earlier, but now the craft is lost—especially the dark room because of digital photography. How do you feel about that, having done so much in silver and then seeing how this medium has changed so dramatically, from black and white to color to digital to now seeing most of our images on screens?

AC: For me, it’s always about the image, no matter what you’re using. Whether you’re using film, digital, print-making, it’s all about the emotion in the photograph or painting or whatever. Capturing those feelings that come through you—if you’re honest and true, it translates so that other people can feel them. It’s not so much the technique as how much emotion you get into it. I think digital is great. I’m able to take old negatives and really make them come alive. I’m for all of it, I’m not against any of it.

HWT: When you arrived in New York, there was the Beat movement happening in the Village, jazz was in its golden age and the Civil Rights movement was starting to catch a lot of national attention. Was that all when you were—

AC: I was in the middle of all of it, but for me, it was always about moving the art forward more than it was about racial consciousness, though I was one of the founding members of Kamoinge and I was also in AfriCOBRA and we really stressed the possibility of arts for our people and showing them in a positive light. I was concerned most about the art. I got out of advertising and photojournalism in 1968 and I went to Brazil. And when I came back from Brazil, everything changed in how I approached my work.

HWT: What was happening in Brazil?

AC: Well, nothing! [Laughter.] I just wanted to get away from advertising. I had a studio and an agent and everything, but I was tired of doing ads for toothpaste, or the army, Con Edison, all those kinds of things. The commercial world was unapologetically white; there were only a couple of black guys working on that level back then. HWT: You don’t hear so many stories of African- American artists who were like, I’m tired of doing these big jobs so I decided to go to Brazil. You hear of artists going to Europe, Paris—but you went to Brazil. What was that like? That was also a great moment in music and culture in Brazil. AC: It was fantastic. It opened up a whole thing for me because of the Afro-Brazilian thing. I lived in Bahia. I had originally gone there to do a job for Esquire, and the guy who was my contact said he was only going to give me part of the money because he wasn’t going back to America. After I was there for a while and saw how beautiful Brazil was, I decided I wasn’t going back to the States either! HWT: So you were on your own journey then? AC: Yeah, I got there and after I met all of these different people, I felt comfortable and ended up staying almost a year. I wasn’t ready to come back but I had to. I had my work, business and everything. I came back to New York, and for two or three weeks I was just depressed!

HWT: What made it so special for you?

AC: I just felt all the different colors of the different people—the Indian with the African and the African with the Italian and the Brazilian—it was just a beautiful culture. I felt a blend of love among the people. I was living on Afonso Celso Street, which is a black part of Bahia, and there wasn’t all that racial tension. It was there, but it wasn’t as overt as it is now. I felt at home. I met Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, all of those guys. They were young kids at that time and they came to our house because we were American— me and my friend Roz Allen—and they wanted to know about America and what was going on with the Black Arts Movement. At first they thought I was Stokely Carmichael. I ended up going on television and talking about what was going on in America, but I was trying to escape all of that stuff; I didn’t want to be bothered. I did go down south after Medgar Evers was killed. The NY Herald Tribune had a grant for artists, so I got a grant to go down there and photograph what was going on, but I wasn’t so much concerned about trying to document. I was more about the things that were happening internally with me.

HWT: I’m fascinated by the breadth of your work—there’s your political work and commercial work, like photographs of people like Mick Jagger, Jane Fonda, Katharine Hepburn. Was there anything you did not want to do? Very few people have such a broad legacy.

AC: I didn’t want to work commercially, and I didn’t want to work for assistants and worked with a lot of the important photographers in New York at the time, including Lillian Bassman, Gordon Parks and others. Gordon said to me: you don’t want to work at Life magazine because you already have a point of view and a style, and if you work at Life magazine, they’ll kill that. I also went to Ebony magazine and met Moneta Sleet Jr. He was a really nice guy and he said, you don’t want to work at Ebony. I said, I need a job! And he said, you have your own style already; if you work at Ebony they’ll kill you like a work horse, ‘shoot this, shoot that.’ That kind of took me out of the magazine business.

HWT: And that’s why your book is called Personal Vision.

AC: It’s called that because it’s my vision, what I feel and think about images and photography, painting, the whole thing. I realized that was really the way I was trained, even though I was in school with journalists like Paul Fusco and James Coralis. We were in class together at Ohio University where we had a class of about 10,000 students and out of all of those students there were only 22 black students, so we all knew what we were doing and kind of hung out together because Ohio was still racist at that time. We couldn’t get haircuts in the town, so we started cutting each other’s hair, and there were places we couldn’t go because we were black. We started integrating places and being very revolutionary, and they called the National Guard at one point because we started real trouble by sticking in the barber shop and not moving and going into places where we would have to go around back to be served—so we would go around back and get our beer or whatever and then we’d go in the front door and sit down. Of course, they went crazy and called the police. All of this wasn’t necessarily making the news, but we were really angry about the way things were going. It had nothing to do with taking pictures, nothing to do with art, just the fact that we were black students. A lot of these kids that I went to school with came from good black families. They didn’t grow up in the hood; these were the kids whose parents were educated, whose parents were doctors and lawyers. It wasn’t about being ashamed of being black—we were proud to be black. This was before the Black Arts Movement. I had a black family with a lot of love—Thanksgiving, Christmas, there was 20 people at the table, aunts, uncles, cousins, everybody. I experienced a lot of love growing up, so I knew who I was.

HWT: Did you know that you were part of a historical moment? That you were living through and making history? All the names that you were interacting with and the things that you were doing are things people read about now.

AC: No, I didn’t think about it that way. Not until much later. I was probably 50 years old before I realized that the things I had done and the things I had lived through were a part of history. I was just concerned about being a photographer. I didn’t care about the other stuff. I didn’t want to take any time away from the work I wanted to do. I loved taking pictures from the time I was 15 years old. I never thought of it as a job, or an art, or anything. It was just something that I really loved to do.

HWT: What would you say to a younger version of yourself—if you were able to say to yourself at 18 years old that you’d be an internationally renowned artist who traveled the world and shot films and ad campaigns.

AC: When I was 18, I wouldn’t have believed that I would have the career that I’ve had. I’ve been working on my website now and my agent is putting things together and she called me and said, “Jesus Christ, you lived two lifetimes already!” I’ve never really thought about it, which is to a fault in some degree, because there’s a lot of stuff I didn’t write down. For me, it was about living my life, not a life that was prescribed to me by the government or whatever. I thought my life was important because the connections I had with my spirit let me know that I had something to do.

HWT: You were part of Kamoinge and AfriCOBRA, which are very community-oriented movements. It took 40 or 50 years for people to catch up to what you guys were imagining then. Photography wasn’t even seen as an art form when you were starting— much less was there a space to be a black artist photographer. You have an ability to see beyond what the world thinks you can and should be, and that’s part of what you talk about in terms of being on this spiritual quest of self-expansion and exploration, but you’ve also stayed rooted to the African- American community, and the international African diaspora community as well.

AC: I look at it like this: I was born black and then I became an artist. A black man living, born and raised in America, and that’s enough. I don’t have to say that I’m doing pictures of black people, or that I’m socially involved—I’m a black man. Whatever is going on, I’m involved. I can’t not be involved. I don’t have to make a point of it. I’m proud, I’m black, I grew up that way. I don’t have to go on talking about it and screaming about it. With Kamoinge, I didn’t want to use that name, because it was a label. I like the name we first had, which was Camera 35. I liked that name because it dealt with photography, and that’s what I wanted to stay with, so I fought everybody. [Laughter.] Ray Francis and I ware the only ones who went against it.

HWT: I knew all of you through my mother [Deborah Willis] and her work at the Schomburg Center. The only photographers I knew growing up were the black photographers: Moneta Sleet Jr., Gordon Parks, James Van Der Zee, you and Roy DeCarava. When I went to college, I learned about W. Eugene Smith, and maybe I knew a little bit about Ansel Adams beforehand. I actually had an almost reverse education about photographic history. I really feel privileged to be able to witness the broadening awareness of our society, of the work that people have been doing for more than half a century, and I’m really grateful because I don’t think my mother would have had the audacity to do a lot of the work she did if it weren’t for you all. So many of us are in the legacy of Gordon Parks, just by him going places he wasn’t supposed to and refusing to be marginalized.

AC: All of that is true. And Deb’s history book was huge—nothing like that existed before. Nothing. You had a really good grounding before you went to college. You already had it going on before you found out about all of these other guys.

HWT: You’ve always had this signature smooth look—the scarf and the hat. [Laughter.] Is that intentional?

AC: It’s energy. You ever meet somebody for the first time and you shake their hand and they give you that limp hand and you go, ugh, and just don’t get a good vibe? And then you meet somebody else, and it’s a great vibe, and you get along right away? That’s the energy that’s coming from that first person and coming from you, and it’s invisible to the naked eye, but it’s a very real energy. One of the things that kept me in photography was the fact that I could take a picture and show it to somebody and they would talk about whether they liked it or whether they didn’t, and to me, what they said about the work was a window into who they were. If I went to a top magazine to show my work, and usually they were white people, whatever they said about my work, I listened because it told me who they were.

HWT: At 83 years old, you seem as passionate about making images and doing work as—

AC: Oh, yes! Look, I had Romare Bearden, I had Jacob Lawrence, I had Norman Lewis, I had all these guys around me. All these guys worked right up until the end. They did not slack off. These were my heroes. When I came to New York, I met these guys and they were the people to know, to be friendly with, to find out about. They were carrying on something, but hardly anyone was paying attention. I had a show at the Kenkeleba House Gallery, and it was great. I felt so good to be there. I felt that I had arrived. I didn’t care about what uptown was doing! I was with the guys who I felt were the most powerful artists on the planet.

HWT: Are these the things you talk about in your new book?

AC: Yeah, I tell stories. How I grew up and when I came to New York, the different people I met, what I did, my experience living as a photographer, as an artist. You can read it in one sitting! I’m getting good comments from people, regular folks, they love it.

HWT: I’m grateful to get this opportunity to talk to you. It’s given me a chance to see things I hadn’t seen and known before.

AC: Cool, because I appreciate what you’re doing, man. Question Bridge was a great concept! And the other stuff you are doing is great too—the Nike series with the branding and the body and the basketball and the chain—all of that is great.

HWT: It means a lot to me to hear you know about this stuff.

AC: It deals with society to a certain degree, but it’s your vision. That’s what I think a lot of these young photographers are missing— they have to deal with their own vision. I call a lot of the younger photographers today visual entertainers.

HWT: I know what you mean. Thinking about what you’ve experienced since 1958 when you came to New York, do you have any advice for someone who is arriving in the same city now with their camera and their hopes and dreams the same way you did?

AC: Listen to your inner voice or to your spirit or whatever you want to call it. That’s where you’ll find your originality—you won’t find it looking outside, you’ll find it looking inside. It’s good to look at other people’s work to see how things are done or how really good photographs have meaning and last through the ages, but until you get in touch with that spiritual part of yourself, nothing will happen. We need each person to express what is going on with them, and it has to come from inside. To thine own self, be true, and that can be very hard, because if you stand still in one place, you’ll get the good, bad, depression, no money, a lot of money— you’re going to get everything that people are moving around doing, even if you’re standing in one place. So get out there, get into life. You have to understand living and dying to be an artist and you have to live through the pain and the joy. To be an artist you have to be able to express emotion. You use the good and bad experiences in life. Great art lives beyond its time because it has emotion, and emotion goes beyond life and death. Work has to have life in it. Expression is what will keep you going. Don’t let anything stop you from what it is that you want to do, your dream. Dreams become realities. They may not come right away, and if they did you’d probably abuse them.

HWT: You wouldn’t appreciate it.

AC: Yes! You wouldn’t appreciate it. You have to make that experience in life. But if you’re passionate about it, and you love it, then you’re halfway there already.