For this special issue of The Critics’ Table, Jarrett Earnest follows the boom clap of his heart, writing not about visual art, strictly speaking. Instead, he takes us to the final night of Charli XCX’s 2025 Barclays Center concert and then to the movies, where—with self-indicting savvy—the pop star’s fake/real tour documentary brings Brat summer to its long-awaited, triumphant end.

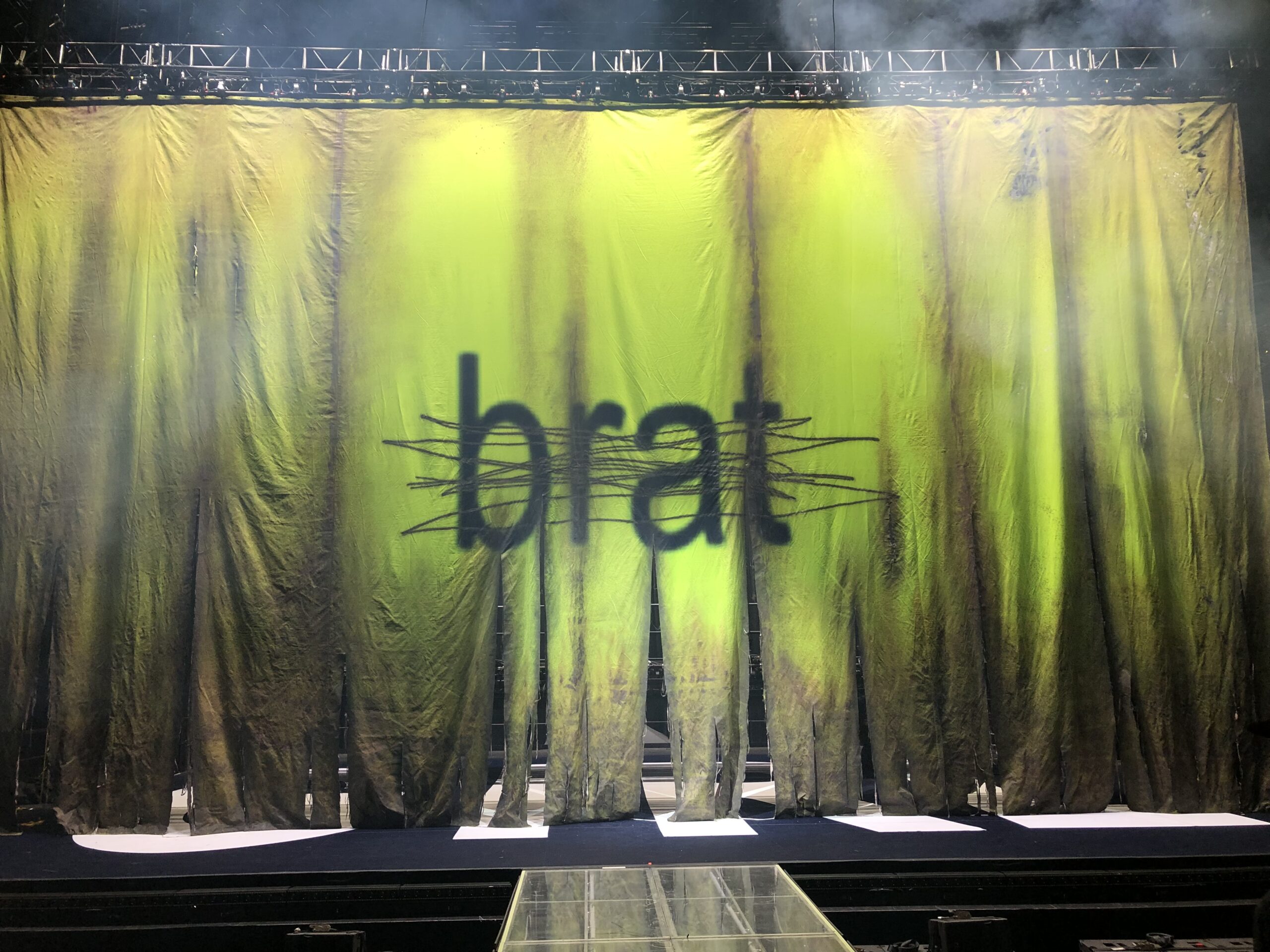

Last year, one of my friends got a job painting the huge curtain for Charli XCX’s stage show, the “brat”-emblazoned backdrop that prolonged 2024’s “Brat summer” into the fall, then winter, then spring. My friend’s job was to cross out the four-letter word, applying faux dirt and graffiti to the banner, adding the appearance of wear and tear before each show, gradually transforming the pristine, digital-green expanse into an enormous, tattered rag. The pop star’s conceit was that the phenomenon was getting worn out—for her, if not for her fans. As a gesture by an artist at the height of success, this seemed both incredibly savvy and like the very essence of cool: Charli freeing herself to move on and do something else, all the while still giving the people what they wanted.

When the U.S. leg of the tour culminated in four sold-out nights at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, my friend invited me to the final show. It seemed like it would be fun, even if I didn’t particularly care about the concert. After a few frozen margaritas and a half-tab of acid, I found myself in the center of the vast crowd. When the lights finally went down and Charli’s track began to play, there was my friend’s defaced “brat”—the scenic anchor for a stark performance concept. The stripped-down spectacle’s other visual elements included constant strobing lights, a glowing battle rope hanging from the ceiling that Charli would wiggle like a noodly lightning bolt, lots of fog, and—for the concert’s climax—a column of rain. Charli strutted from one side of the nearly empty stage to another, posing, stalked by camera people; she walked under the stage, the audience watching her, always, via live video feeds on Jumbotrons.

My friend said his favorite part, night after night, was turning away from the stage and just looking out into the audience, seeing how fucking psyched the crowd was, the energy of thousands of people (at Barclays, around 17,000) singing along with every word. The other thing he’d see was a sea of glowing rectangles, virtually everyone filming, their phones raised high to capture Charli’s tiny, distant figure on stage, as well as big-screen close-ups of her.

It’s a condition endemic to the arena show. For everyone there, not to mention everyone seeing clips online, the performance is for the screens. In this sense, the Brat tour’s austere art direction, which did nothing to distract from the raw effects of this hyper-mediation, seemed practical as well as critical, commenting on the relationship between the fans and the screen, the image and the person, and perhaps the artist to herself. Continuous, pervasive live filming seemed to grant ever greater access to Charli, while simultaneously erecting a barrier, a protection, in the same way her oversize dark glasses seemed to be a shield, holding the fantasies of intimacy and connection at bay, deferring the parasocial promise of such performances. You couldn’t help but feel she was totally isolated up there.

At the end of the roughly 80-minute show, the screens flashed a sequence of text, a message from Charli: “I’ve been thinking a lot about / brat summer / and whether it’s / FINALLY / over????? / and I thought it was… / BUT ACTUALLY…”

It turns out that Brat would linger on, as long as people kept paying for it. Which is to say there was something deeply ambivalent, even conflicted, about the entire production. It seemed edged with an unavoidable cynicism, I thought, this drive to push insane commercial success to even greater returns, to wearily try to make “Brat summer” last forever.

Suitably then, The Moment, director Aiden Zamiri’s debut feature—“a movie about Brat and Charli and a tour but none of it happened but maybe some of it did,” per its tagline—arrives in the dead of winter. “Based on an original idea by Charli XCX,” who stars as a fictional version of herself, it’s a mockumentary about the making of a concert film of an alternate-reality version of the Brat tour. Plausible stand-ins for her real-life creative team and record label reps are played by actors, pushing her non-stop to agree to “collaborations” with influencer-types, to paid posts for hotels in Ibiza, and to a Brat-green credit card aimed at ensnaring “a young queer market.” The result is a combination of the Spice Girls’ tongue-in-cheek Spice World, 1997, and Lisa Kudrow’s proto-reality TV masterpiece The Comeback, 2005-2014, trading the former’s high camp and the latter’s deep cringe for a deadpan satire all its own.

In The Moment, every person we see around the singer is on her payroll, with a vested interest in maintaining her non-stop schedule to some degree. She has no friends. Her longtime art director, Celeste (Hailey Benton Gates), attempts to make a concert very close to the one that actually happened but is undermined, thrown over for sleaze-ball filmmaker Johannes (Alexander Skarsgård) and a vision antithetical to her concept. When surveying Celeste’s proposed intensive strobe lights and large flashing signs, one reading “CUNT,” he advises that they consider family audiences. Celeste retorts, “She’s literally singing about cocaine.” Johannes asks, “literally or metaphorically?” (It should be noted that “CUNT” did not appear on the screens at Barclays Center, and the show was in fact family-friendly—literal or metaphorical blow notwithstanding.)

Charli, overwhelmed and unsure, basically defers creative responsibility, allowing the record execs and filmmaker to create the production they want, replete with a giant bedazzled cigarette and lighter on stage, high glam costumes, lots of smiling, no sunglasses. Almost no Brat songs appear in the movie except in shattered fragments; they’ve been replaced with an electronic score, undulant and discordant, by her longtime musical collaborator, producer A.G. Cook.

For the one song we do get, Charli is dressed in a short green glittering dress, like Kylie Minogue as the green fairy in Moulin Rouge, absurdly hoisted in a harness and wires high above the stage. The track “I might say something stupid” plays, her self-doubting pop lament (“I don’t feel like nothing special / I snag my tights out on the lawn chair / Guess I’m a mess and play the role…”). In a perfect feat of physical comedy, she’s totally still, her feet flat as though she’s standing on an invisible floor, while she calls down to her team, repeatedly, asking if she looks stupid. Hanging in a void, literally and metaphorically, she receives only obsequious assurance. There’s no one she can trust.

The smartest thing about this movie, the key to why it works, is that everyone is made to look bad. Each character is shallow, delusional, and self-serving. Charli herself is shown firing her longtime collaborator and capitulating in desperation to the demands of her career machinery. The Moment is very funny, but the humor is razor-edged, and it’s never totally clear which way it’s cutting. In a scene where the characters representing the film’s production team consider that a temporarily missing Charli might in fact be dead, they almost eagerly bring up Amy, 2015, the “powerful” cinéma verité documentary about Amy Winehouse, which won its director, Asif Kapadia, an Oscar among other accolades. For many around her, she might prove as profitable dead as alive.

Near the end, Charli leaves a long voice memo apologizing to Celeste, saying she knows the new version of the tour is artistically bankrupt, and yet she’s going on with it, joking, “You should come.” And for the finale, we get a sizzle reel for the concert film-within-the-film, a montage of Charli vamping with backup dancers, awkward faux-sexy chair-ography à la Eras Tour, the pumped melodrama of her spotlit and suspended midair. Brand logos flicker subliminally in lightning-fast edits, and product placements are peppered throughout. It’s like a rhinestoned, laughing inversion of every decision that the real-life Charli made. The effect is as searing and self-indicting as it is hilarious, showing the contrast between her actual tour, the one in the film, and the compromises they both entailed—different in degree but not in kind. In playing a fictional version herself, Charli dramatizes not only her own lose-lose predicament as a celebrity, but an essential aspect of contemporary life. It’s a depiction explicitly pitched against the pandering “authenticity” and “accessibility” of both social media and the behind-the-scenes concert-film genre.

That a celebrity of her status could get away with making something this slyly subversive and authentically fun is astonishing. This is as close to art as pop gets, its achievement greater precisely because Charli and The Moment wage their critique far from the siloed and symbolic realms of the art and literary worlds, on the largest stages of culture and capital. And, most radically, they leave their own ambivalences intact, exposed. The Moment enacts an autopsy of “Brat summer” and its aftermath from the inside out, delivering on what that soiled curtain promised: “brat” scratched out, torn asunder—a conclusion. It is an artistic declaration of independence. And it makes undeniable what has perhaps been long apparent—that Charli, with her closeknit collaborators by her side, is the most intelligent and interesting pop star of our moment. May the long season of Brat finally end. May Charli XCX do exactly what she wants, forever.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Julie Delpy Knows She Might Be More Famous If She Were Willing to Compromise. She’s Not.

Our Critics Have Your February Guide to Art on the Upper East Side

Move Over, Hysterical Realism: Debut Novelist Madeline Cash Is Inventing a New Microgenre

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?