Margaret Lee was in the midst of the most intense creative block of her life last year when she did something out of character. She opened up a self-help book: Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way.

The 1992 cult classic has been subjected to a fair amount of derision for its hokey, woo-woo approach to “creative recovery.” When, during the second week of the 12-week program, the book instructed Lee to hang a sign in her workspace calling on the “Great Creator” (“I will take care of the quantity, you take care of the quality,” it read), she felt her cynicism welling up like a sneeze. “You feel every part of your brain being like, No way, no way, no way," Lee remembers. “But I’d never had artist’s block like this before, and nothing else has worked.” So she kept going.

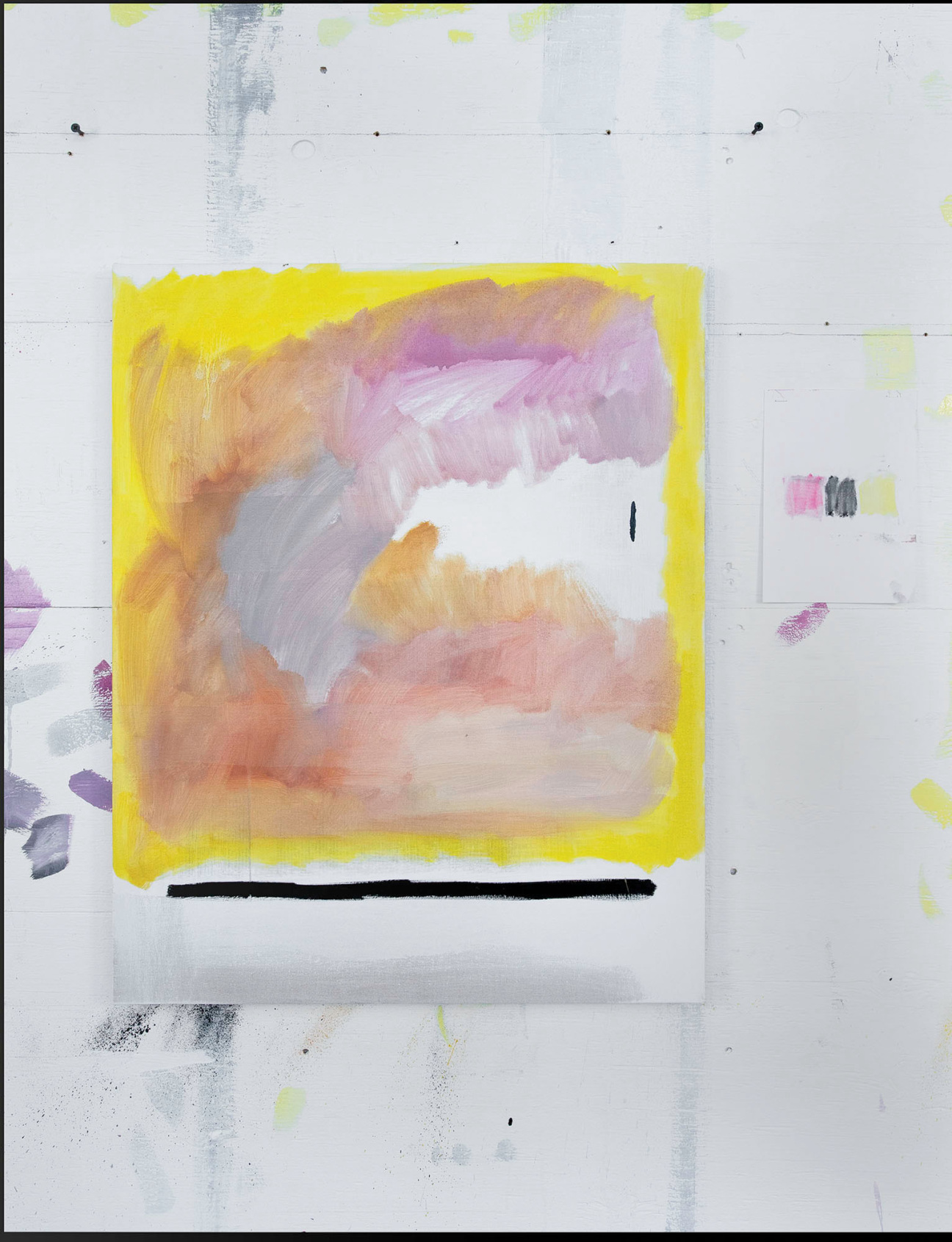

The fruits of her labor are on view in “Life Lines,” which opens on April 25 at Jack Hanley Gallery. The brushy abstract canvases bathed in sunny yellow represent a significant departure for the artist, who is best known for making hyperrealistic plaster-cast sculptures of produce (potatoes, watermelons, tangerines) that toy with our relationship to capitalism and desire.

Lee threw herself into painting during the pandemic, when supply-chain problems and shuttered foundries made it difficult to produce sculpture. The transition coincided with her deepening study of psychotherapy, which taught her to push back against her tendency to over-intellectualize feelings and experiences. “I thought therapy was you being very explicit about your problems, and having your therapist bear witness,” she says. “That was [also] what my sculpture was—building an argument.”

Reading psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud, Mária Török, and Nicolas Abraham—as well as The Artist’s Way—gave her permission to loosen her grip in both life and art. In her own therapy, she worked to cultivate a truer, almost pre-verbal version of herself. “Becoming inarticulate is an extremely scary thing,” Lee says. “It’s the most vulnerable I’ve ever been.”

As an artist, “becoming inarticulate” meant rejecting the silver and black hues she’d been working with previously, which she felt were too cool and detached, and embracing warmer, softer colors like mauve, blue, and yellow. It meant stripping the works of all sculptural elements with which she was previously associated. It meant preparing rigorously (through sketching, color theory, exercise, and writing) so that she could truly let go when she stepped in front of the canvas.

In recent years, Lee has been thinking about her early sculptures differently. Her father immigrated to New York from South Korea and worked as a greengrocer, but his business never got off the ground. Years later, Lee used fruits and vegetables as her entrée into the elite art world. “When I was making those watermelon and potato sculptures, collectors would tell me funny stories, like, ‘My housekeeper put it in the fridge!’” Lee says. “I used the very thing my father attempted to enter the American middle class with, to gain access to these spaces.”

In contrast to her confident sculptures and installations, the paintings in “Life Lines” embrace uncertainty. They aren’t striving for anything in particular and they don’t need your approval. Lee has always been a multitasker: She continues to work as an assistant to Cindy Sherman and volunteers in her Chinatown neighborhood (although she no longer works at 47 Canal, the gallery she co-founded).

Now, she’s allowing her art to be about the process of making and the process of processing. “What’s flowing is a very anxious, shaky line, which I’m kind of excited for,” Lee says. “I’ll make more paintings. It’s a practice. Each one is not so special.”

"Life Lines" will be on view from April 25 through May 25, 2024 at Jack Hanley Gallery in New York.