According to the website for Telfar Clemens’s eponymous brand, “It’s not for you—it’s for everyone.” As an advertising slogan, this statement seems counterintuitive. In recent decades, many of the world’s most successful brands have elected to direct their slogans at a singular “you:” L’Oréal’s “Because You’re Worth It;” Gatorade’s “Is it In You?;” Verizon’s “Can You Hear Me Now?” In America in particular, consumption and individuality are two sides of same coin, to the extent that the 20th century was dubbed “the century of the self.”

We are now well into the second decade of the 21st century, and data mining and ultra-targeted online advertising have rendered both buying and selling even more segmented and individualized than we thought possible. But Telfar’s syntactical sub is meant to stand out. Last November, Clemens was awarded the 2017 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund Award. In this new era, fashion-conscious consumers want what Telfar is selling.

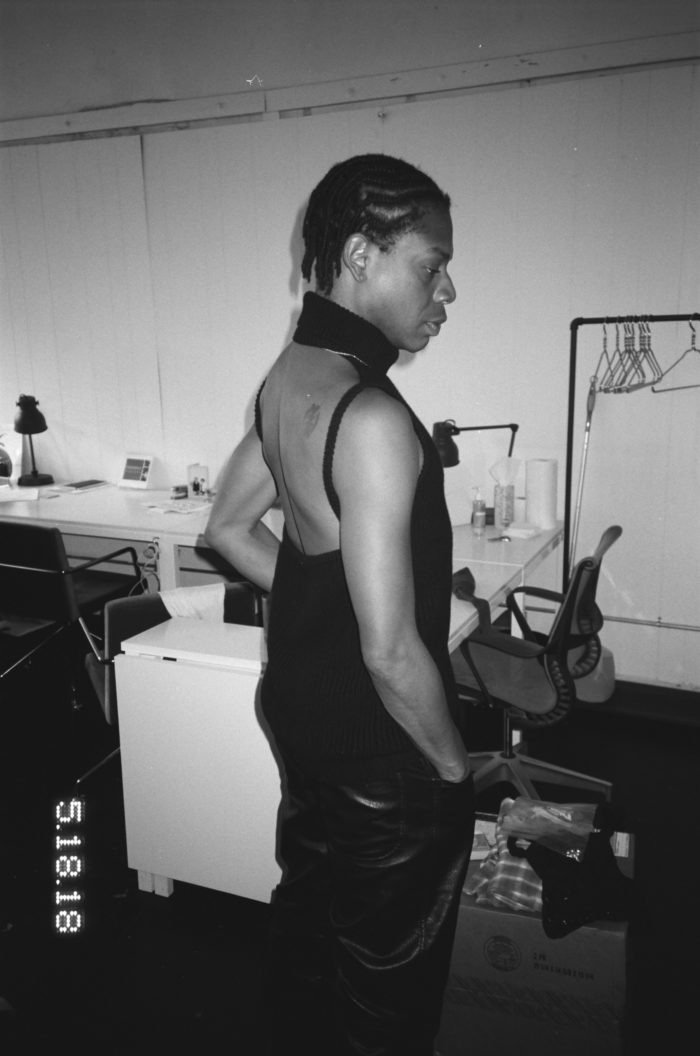

In a phone conversation a few weeks ago, I asked the Queens native what clothing meant to him growing up, and why he felt the need to start his own brand. His reply was straightforward: “How I dressed was the only choice I had.” There is a tendency in aesthetic discourse, especially within the academy, to relegate fashion to a lower level than Art. But as Clemens points out, deliberate choices about clothing can be a crucial means of self-expression, especially for those who find their identities otherwise overdetermined by social politics, economic realities and/or cultural assumptions. In fact, self-styling is perhaps the most ubiquitous art form—the only consistent aesthetic act in most people’s lives. Clemens often describes his work as “horizontal”— horizontal fashion, horizontal relationships. He aspires to “accept everything as it is, without categories.” He argues that style transcends barriers of exposure, access and ultimately of that most divisive mechanism of class separation: taste.

Clemens started making clothes at age 15 and debuted his company in 2005, when he was 18. He and his brand came of age together. The last decade and a half has seen the rise of social media and the ubiquity of e-commerce, as well as the ascendance of athleisure and streetwear as cornerstones of contemporary dress. The internet’s stochastic potentials have undermined the rituals of the fashion industry and destabilized the mechanisms through which it confers relevance and prestige. Clemens is a natural in this new climate, and he is in the business of dismantling; Telfar is often called a conceptual brand, in part because it is stuck in the oblique, mercurial limbo between art and fashion, and—to its credit and its benefit—has managed to evade these distinctions. “Fashion people considered my work art. Art people considered it fashion.” The muddying of social, personal and industry categories has long been crucial to Telfar’s initiatives.

In practice, this can be as simple as bringing people to places they may not usually go or using products to raise funds for social justice initiatives. Last November, Telfar opened a pop-up shop inside the Financial District location of discount department store Century 21 where Clemens shopped as a teenager. The corresponding capsule collection, TC21, was just one component of Next Century, a millennial- oriented boutique within the store that, instead of offering last season at a discount, boasts exclusive, collaborative merchandise released through drops.

Telfar’s offerings included a hoodie, T-shirt and beanie, each emblazoned with a screen-printed Century 21 logo overlaid with Telfar’s own embroidered logo. Shoppers in the Century 21 pop- up could also vote on Instagram for which tentative future products they would most like to see made, merging the roles of professional and in-store buyer by inviting anyone and everyone to weigh in.

Last fall, the brand debuted another capsule with fast-food chain White Castle, also a favorite of the designer. Telfar donated the proceeds from that collection to the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Fund, which helps to bail out minors being held on Rikers Island. This surprising partnership began with a cold call and also resulted in Telfar designing White Castle uniforms for the employees in more than 400 locations. While Telfar engages the cultural meaning and valence of these brands, he also (in this case literally) influences their identities.

Though unquestionably topical, not every aspect of Telfar’s style and positioning is new. In many ways, the brand seems to fit within the lexicon of athleisure that can be traced back at least to the early ’90s. This legacy is visible not just in the kinds of clothing pieces Telfar offers but also in conceptual strategies, like subverting corporate logos and tongue-in-cheek cross-industry partnerships. But an open dialogue with established trends is also part of the brand’s DNA. Telfar has always self-identified as unisex, for example, and in this regard Clemens anticipated, with startling foresight, a dramatic veer away from gendered clothing and from selling conventional notions of beauty. “I kept at what I was doing because I knew it could and would be big. And I don’t mind being copied. The more people copy me, the more customers will recognize and buy my stuff.”

Julie Gilhart—a veteran fashion consultant and former fashion director of Barneys New York, who also helped found the LVMH Prize for Emerging Talent— attested that though Telfar’s work speaks for itself, it is made even stronger by the community he has created. “In fashion, being inclusive and progressive have become trendy recently, but he has always stood by these values in his designs,” says Gilhart. “When he says his clothing is for everyone, he really means it.”

A curious thing about contemporary fashion is the way in which it has transformed the meaning of luxury. Quantifiable metrics of value have become harder and harder to pinpoint now that almost everything is mass-produced, including most “luxury” goods. Both the fashion and art industries fiddle with artificially finite quantities, limited release and inflated, brand-dependent pricing to engender a kind of luxury. A Supreme box logo hoodie, for example, has little to do with expensive materials or rigorous craftsmanship but is instead performative and conceptual. A logo hoodie from Telfar’s F/W 2018 collection is available for online pre-sale at $295.

But can a conceptual brand be conceptual art? The latter is often defined by its ability to masquerade as a variety of different mediums, including those not strictly considered art. Telfar’s particular success is not so much the result of Clemens’s savvy attention to market forces and cultural whimsy but rather of his distance from these things, and his willingness to play with the industry’s conventions, expectations and biases. In a direct-to- consumer world, without season, without gender, without designated arbiters of taste, the line between art objects and fashion pieces continues to blur as clothes shed many of the identifying features once used to demarcate garments and inject them with meaning.

“Telfar constantly shifts our expectations of what a fashion company could be,” says Wendy Yao, owner of LA’s Ooga Booga. “He thinks like an artist. His shows comment on the production and consumption of images, branding and identity, and question the hierarchies of where fashion belongs.”

I asked Clemens if there is anything about Telfar that he feels is misunderstood. He replied that misunderstanding Telfar would be impossible. He is unconcerned with establishing a particular or cohesive perception of the brand. There is no “right” Telfar that consumers might get “wrong.” After all, some of the most dynamic creative initiatives—in art or fashion or any other field— come from unforeseeable collisions of intention, reception and dispersion.