Cady Noland

Gagosian Gallery | 555 West 24th Street, New York

Through October 18

Steven Parrino

Gagosian Gallery | 555 West 24th Street, New York

Through October 18

Is this Gagosian or Filene’s Basement? Less than a minute into the first room of the Cady Noland exhibition at the megagallery’s 24th Street location—only just peering through to the second room and after laughing out loud—I text my colleague Johanna Fateman two lines: “feels like a Cady Noland blowout sale / EVERYTHING MUST GO.”

The buzz around the show broke through before I had a chance to see it. One critic-friend said bluntly: “It’s bad.” Maxwell Graham posted to IG: “What a Waste of a Legacy.” But, after spending sustained time with the show, I don’t think either of these takes get it right. Is it good? Wrong question. It’s a fascinating mess—and among the most interesting gallery exhibitions in New York right now. If it’s a little funny (it is), Noland is in on the joke.

The reclusive New York-based artist’s recognizable lexicon of objects is here: Budweiser cans, shotgun shells, a sheriff’s badge, barricades and A-frames, license plate covers, toy pistols, and whitewall tires. The objects of this no-ideas-but-in-things array appear on, among, or in, plastic bins, clear acrylic cubes, metal baskets, a mini fridge, filing cabinets, and metal pallets. Familiar images repeat too, most notably Patty Hearst holding a long gun as a member of the Symbionese Liberation Front and Lee Harvey Oswald, at the moment he was shot by Jack Ruby. But, here, these greatest hits are notably cropped or further fractured—conveying, I think, Noland’s self-awareness of making copies of copies and so on. One of the real achievements is the uncanny retrospective feeling the spread of works creates and then decreases with further scrutiny of the fragmentary spread.

What do we expect in 2025 from an artist whose subjects have long been American violence, conspiracy, cults, consumerism, punishment, and the carceral? Especially when showing here? Noland herself reportedly once quipped that “artists go to Gagosian to die.” Rather than a funeral, she appears to have staged something closer to an estate sale. It may be that this country has gotten far too conspiratorial, too violent, et cetera. Take, for one example, the rows of tubular metal-framed bunk beds in cells of chain link fencing as seen in press photos of “Alligator Alcatraz,” the South Florida Detention Facility. When I first saw the images, I thought immediately of a Cady Noland installation, or rather, that—through the X-ray of America that is her work—she had predicted it. Everything must go, indeed.

The show does gesture back to Noland’s debut solo exhibition at White Columns in 1988. Specifically via the posthumous presence of the work of Steven Parrino alongside Noland’s in one gallery. (For the White Columns show, Parrino had loaned from his collection Noland’s sculpture Action/Duty, 1986, a walker adorned with a police badge, holster, glove, and book.) The tight gallery hang may be a good introduction to Parrino’s punkish works on paper and handsome, larger, monochromatic, often pierced, torn, or distressed, paintings, but the combination doesn’t do Noland’s exhibition any favors, as it never achieves particularly dynamic or revelatory juxtapositions.

There are no notable new developments in her work here with the exception of the several “SALE” signs in black or red, which feature typographical illustrations of pointing hands. (These manicules originate in the drawn marginalia of medieval manuscripts, a precursor to underlining in which disembodied gestures seem to announce, I saw this and so might you.) They strike a clangorous old-timey note amongst Noland’s still-contemporary feeling assemblages.

The total effect is maximalist, humorous, and a little disconcerting. Noland’s usually tightly controlled arrangements give way here to sprawl, recalling last fall’s gallery trend toward mess. (Noland’s show is closer to Fischli and Weiss’s brilliant “Polyurethane Objects” than to Michael Krebber’s studio dump.) In the end, Noland toys with, rather than satisfies, expectations. A show that many registered as “bad” is instead a self-aware reflection, tracing a history of American culture from Reagan to Trump that parallels Noland’s own career, as if to say: This is still America, but dumber, persistently violent, ever more conspiratorial, and certainly for sale. Maybe Noland is giving us the show she thinks we—or Larry Gagosian—deserve.

The perfect counterpoint to Cady Noland at Gagosian, is the potently diminutive show, “IKEA,” in the second-floor apartment gallery CICCIO in Brooklyn Heights. It takes up many of the same themes (commercialism and industrial design, political violence and counter-cultural movements) while looking across to Europe from America. The exhibition restages an installation by Thomas Eggerer and Jochen Klein (1967-97), curated by Julie Ault, made for the windows of Printed Matter in 1996. This was when Printed Matter was in Soho, while the neighborhood was changing from an industrial district to the brand- and design-driven commercial center it is today (but before the content creators made it their plein air sound stage). I can’t imagine that the beloved artists’ bookstore was a better venue than CICCIO’s emptied out living room space, with adjacent tiny kitchen and old, eponymously on-brand kitchen cabinetry. The show consists of reproduced ads, quotes, film stills, wall drawings, and Ikea-branded pins (you can take one with you from the pile in the fireplace).

The 1996 artists’ statement notes that the first Ikea store in West Germany in 1974 coincided with a spike in German left-wing “terrorism” by the Red Army Faction. And the show weaves, with a minimal number of strands, a series of connections between seemingly conflicting ideologies. A quote across the cabinets in the kitchen from the founder of Ikea, Ingvar Kamprad, states: “Is it possible to equate a social ambition with a commercial business idea?” In other words, he seems to ask, how can the functional avant-garde designs of the likes of Aalvar Aalto (photos of his iconic chairs appear here too) be combined with emerging hippy subcultures to revolutionize the home, and sell accessible, well-designed consumer products? But the show goes farther, asking us to look deeper: Kamprad was associated with Swedish Nazi and fascist movements in his youth, before he sought the glossy mainstream by selling furniture and creating a lifestyle brand that borrowed from left counterculture.

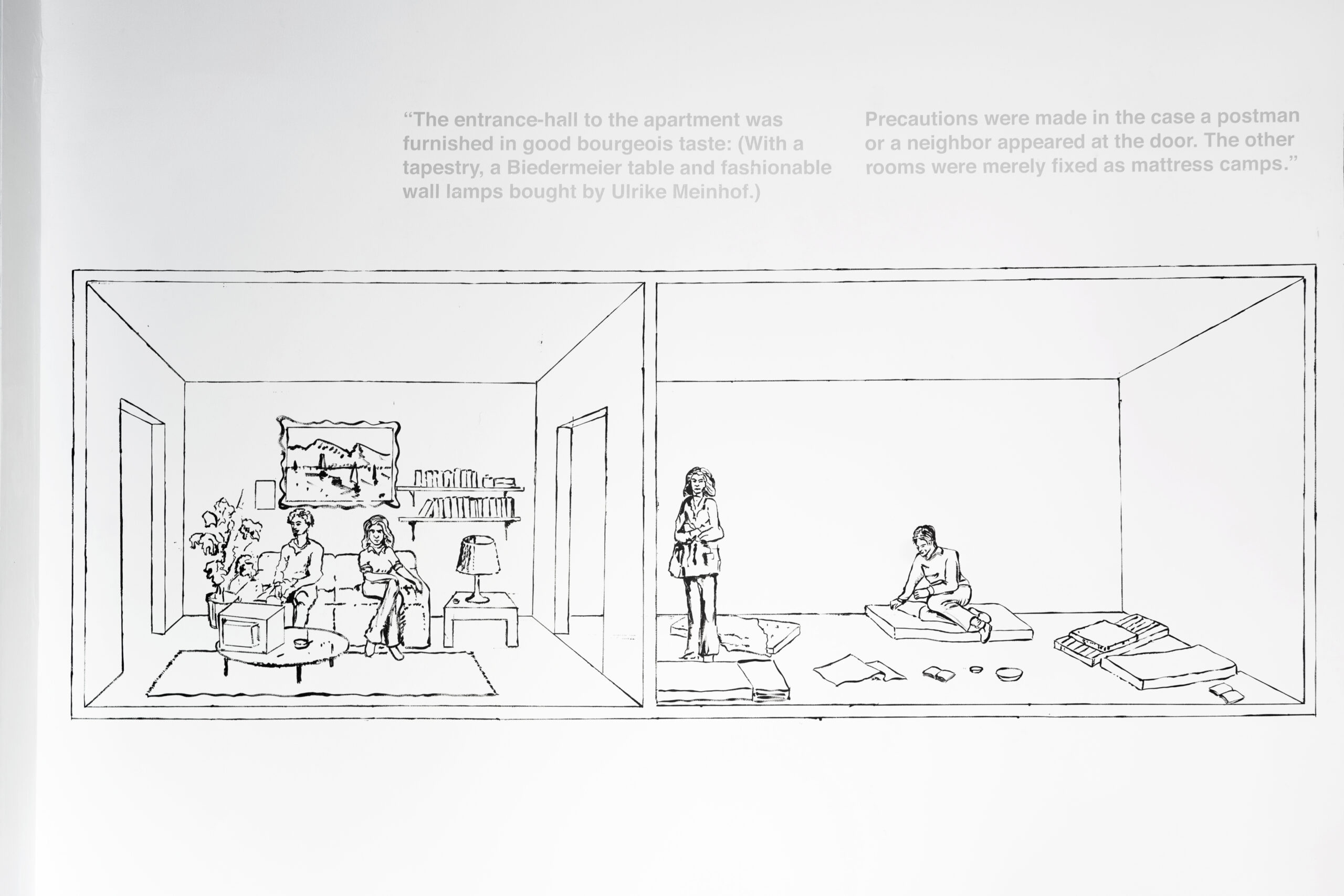

The space of the domestic interior is given another view in a mural drawing showing two rooms: a front room furnished in “good bourgeois taste,” so as not to raise the suspicion of a visiting postal worker, with a deeper room sparsely furnished with mattresses, where a cell of revolutionaries could plan their next action while sleeping collectively.

With so little, this tiny exhibition does as much or more than that expanse of excess at Gagosian, across the East River, in that newer, gleaming commercial district—Chelsea. It got me thinking about how often, in New York, the dynamic of an exhibition is partly defined by how the work fills and transforms real estate. A big art palace can awkwardly hold too much, while a small gallery can layer history across two continents and tell a complex tale in poetic concision. One is farcical. The other is like magic.

[INSERT_AD]

in your life?

in your life?