During his time as an MFA student, Titus Kaphar recalls skepticism he encountered about his subject matter: “Why are you painting this?” a Yale professor once asked him—“Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker already had this conversation.” Fifteen years later, the exchange reverberates in his vision for NXTHVN (“Next Haven”), the 40,000-square- foot arts incubator he’s created in New Haven’s largely Black and brown Dixwell neighborhood, walking distance yet worlds away from the University’s arched entryways. “That is verbatim what was presented to me,” he explains of his professor’s misconceptions and the hesitation it caused him at the time—another sign of how overwhelmingly white and insular the ivory tower still is. “My revolution is for freedom,” Kaphar says. “When it comes to Black and brown artists, that means the freedom to tell the story that you want to tell and to make the work you feel compelled to make.”

A former ice cream factory transformed by Yale School of Architecture dean Deborah Berke into a modern landmark, NXTHVN’s light-filled industrial studio space rivals any I’ve visited on either coast (a lifesaver for the class of 2020 fellows during lockdown, as they, unlike so many artists, were able to access the building and continue making art through the pandemic). Kaphar’s vision for its curatorial and artist fellows program is a testament to his younger self, who he wishes he could encourage to, “in the most clichéd way, follow your heart.” But his experiences did provide a curriculum for surviving the art world as an artist of color. “NXTHVN is an opportunity for me to go back in time to when I was having conversations with faculty,” he says. “I’m able not only to see these young artists’ work from a formal perspective, but to get into the weeds of its social, political and emotional impact as well.” Core to NXTHVN’s mission, fellows are paired with area high school students—a paid apprenticeship, endowed in part by Kaphar’s gallery, Gagosian—who get to work side-by-side with an artist or curator and learn from their practice. “Creativity is an essential asset,” says Kaphar. “In order to be successful, you have to be able to imagine something you don’t see. That’s the power we want to impart to the young people with us.”

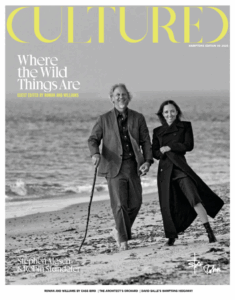

Yet to appreciate NXTHVN, you have to get to know New Haven. I grew up a mile away, but had never been to Dixwell before I visited the building, a construction site, on assignment in 2017. “The way New Haven is laid out, a mile is another city,” he says as we enter the glass atrium and street gallery, which has just reopened to the public (in late July) post-COVID shutdown; Tavares Strachan’s neon yellow You Belong Here glows on the brick wall, visible from the sidewalk. Executive director Nico Wheadon and I meet to tour NXTHVN’s inaugural exhibition, “Countermythologies,” which mines archival memory and oral history. Organized by the previous year’s curatorial fellows, artists include Firelei Baez, Bethany Collins and Jarrett Key. September programming showcases “Pleading Freedom,” a collaboration between Kaphar and poet-memoirist Reginald Dwayne Betts, and Kaphar’s TIME magazine cover painting, Analogous Colors, displayed for the first time in the flesh.

“When we started, people told me, you should build NXTHVN downtown or over there,” Kaphar says. “After several conversations like this, I began to realize what people were saying is that communities like ours wouldn’t appreciate ‘high architecture.’” On my initial trip, when NXTHVN still seemed more ambition than reality, we drove to visit his oil painting Shadows of Liberty (2016), a reimagined portrait of George Washington, in Yale’s permanent collection. “To say that the Yale University Art Gallery is only a mile-and-a-half from here is not to understand this city,” he explains. “To say there’s a place in your neighborhood, around the corner from you, where you have a job, showing international-quality art, that means something. I’m not talking about gentrification, the way it always ends up happening. I’m talking about bringing lasting value for this neighborhood.”

At the same time, Kaphar emphasizes how essential it is for Black and brown artists to generate a broad range of work. “I’m not fighting for folks only to make representational work about social issues in this country,” he told me, after I visited with each fellow in his or her studio. “God, that would be awful. We need artists of color to make minimalist squares that stand as modernist totems as well. We need to make all of it.”

NXTHVN’s 2020 fellows are artists and curators poised to make an impact on their fields. We will be keeping an eye on their creative journeys this year and in the future.

in your life?

in your life?