With A Space for Being, a new exhibition at Spazio Maiocchi for Salone del Mobile Milano (April 9-April 14), Google Design explores how aesthetic experience directly affects your brain. You already know how your body responds to particular design elements—the way a chair’s texture feels on your skin; how space or clutter, by turns, can comfort you; the right color, in the right light, can energize or soothe. A Space for Being was made in collaboration with Google, Muuto, Reddymade Architecture and Design Studio, and the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University. Together, they’re examining what neuroaesthetics—the study of how the brain responds to art—says about the effect of art and design on our physical health and mental wellbeing.

Each room in the multitudinous installation at Spazio Maiocchi has a different design theme, with its own colors, textures, sounds, and scents; there's also a specially commissioned work from Dutch artist Claudy Jongstra, in collaboration with Suchi Reddy, Reddymade Architecture and Design Studio Founder and Principal. Envisioned by Reddy, Google Vice President for Hardware Design, UX, and Research Ivy Ross, Muuto Design Director Christian Grosen, and Susan Magsamen, the Executive Director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University, A Space for Being explores how a particularly designed space can be neurologically livable and affective: calming, happiness-inducing.

Guests are given a custom-made wearable band and sent off to traverse and experience three rooms, sitting on the furniture, breathing in their scents. Meanwhile, the band measures their physical response, such as their heart rate and skin temperature. As the experience comes to an end, visitors receive a personalized analysis elucidating which room made them feel calm and at ease. Ahead of the show, Ross, Reddy, Grosen, Magsamen, and Jongstra spoke with us about what neuroaesthetics can reveal about art, design, and even medicine going forward.

Monica Uszerowicz: Why is the effect of aesthetics on the body important? Staring at a screen for too long is objectively awful for the body, but looking at a painting isn't.

Ivy Ross: They are important, as aesthetics can impact the body both positively or negatively. This is worth understanding because we have control over some of our surroundings. By understanding the impact of aesthetics, we can make smarter and/or better choices about the things we surround ourselves with, keeping a goal of positively impacting how we feel. Viewing a painting, depending on the content of the painting, whether on a screen or on a wall, can stimulate the brain in a wide range of emotional meaningful ways.

Is this more largely related to Google’s efforts to explore the human experience?

Ivy Ross: Given Google Design Studio’s conscious focus on design feeling, this exhibit is our way of helping to make the impact of design more visible.

Each guest receives a personalized readout, highlighting the room in which their “biology shows them to be most comfortable.” I’m curious about how comfort is defined. Is it indicated by the brain’s pleasure centers?

Ivy Ross: During the exhibition, we expose guests to three different environments where unique sensory stimuli enters the brain and is processed through the pathways of the senses—it’s here where the brains perceptual systems begin to be activated. A lot of things happen in the brain as we introduce olfactory, tactile, visual and spatial information. While there is reward activation that definitely happens, we are not tracking the brain’s pleasure or reward centers during this exhibition.

Here we are capturing basic biological information including variable heart rate, heart rate and breathing rate through a PPG sensor We are also capturing skin conductivity using an EDA sensor (electrodermal activity) and skin temperature using a different sensor. Our algorithms analyze these simple markers to suggest what the guest is feeling and where they are most biologically calm. For example, if a guest has lower breathing and heart rate and elevated variable heart rate along with reduced skin temperature in a specific room, we would suggest they are most calm in this environment.

Thinking about the neurological response to aesthetic experience is quite a prompt. How do design and the brain interact?

Christian Grosen: The neurological response is immediate, and that’s also what we believe makes it interesting; it’s your immediate, unfiltered response to the space that you’re in and the elements around you. If you’re in a space for a longer time, you begin to reflect and your reaction and perception might change as time goes on. It’s interesting how your body instinctively reacts to its surroundings without you being directly conscious about it.

What sorts of colors, textures, and scents are in the exhibition?

We have designed three unique spaces, each with different designs, colors, textures, scents and sounds. The spaces have been designed to echo the given sentiment and aesthetics of each room while triggering various reactions. But at the end, how the biology of a person will respond to the given surroundings is subjective to them. At Muuto, we’ve always worked from a strong belief that the elements around us—be it furniture, sounds, light, colors or forms—have an impact on how we feel.

Neuroaesthetics is a proof of that, and shows how environments can influence our biology, thus emphasizing the importance of thoughtful design.

What did you daydream about when preparing for this exhibition, and what was important for you to highlight?

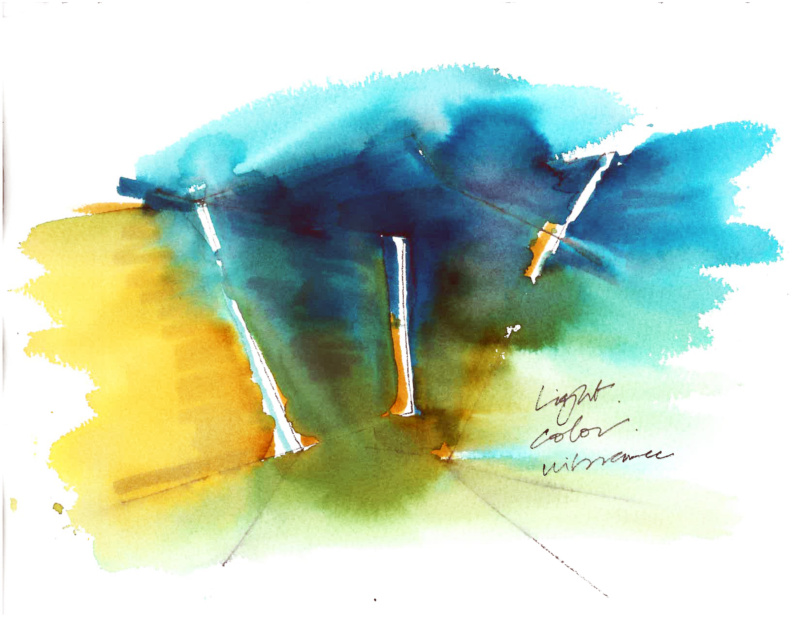

Suchi Reddy: The project presented the perfect format for the mantra I created to guide my practice: "Form follows feeling." Thinking about how our bodies and beings respond to space and design is a constant reverie for me, so daydreaming about these spaces was a fluid fit into my stream of consciousness. I began "feeling" shapes, light effects, textures, and colors that could evoke the characteristics we wanted to define spatially, then assembling them almost like a three dimensional collage, and testing my reaction to them.

The mood of each space was very important to me, so each space has a specific light quality that sets the tone first, and then I layered in texture and color. The music, scent, art and accessories also work to differentiate the feelings in each space, amplifying the visceral experience: in each room, there will be unique music by Trevor Oswalt of East Forest, scent by Mandy Aftel of Aftel Perfumes, art—the specially commissioned piece by Claudy Jongstra, and work by Sabine Marcelis—and accessories working to differentiate the feelings in each space, amplifying the visceral experience.

Claudy, in considering Suchi Reddy's mantra that "form follows feeling," how did you approach making work that considered the brain?

Claudy Jongstra: Our perception is not structured along separate senses, but senses that are cognitively triggered together. This means that if we see a material surface which we know from experience of touch to be soft and fuzzy, our haptic perception is also automatically triggered. When we see wool, we also feel wool, without having to touch it. This makes soft, fuzzy surfaces so attractive to our senses.

Susan, you’re the Executive Director of the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins. How has the field of therapeutic art expanded in recent years? Can you talk about how art is healing?

Susan Magsamen: The field of therapeutic art has expanded exponentially. Hospitals, community arts organizations, cultural arts programs, artists and architects are working separately and together to explore how the arts impact health, well-being and learning. There is significant integration between arts, technology, education, engineering and other domains—and universities, professional and community organizations and businesses are beginning to collaborate to address complex issues.

Basic neuroscience research, and more specifically research in neuroaesthetics—or how the brain changes on art—is producing new knowledge about the mechanics of the mind. From sensory, motor and reward systems to cognition and neuroplasticity, we now know more than ever about the brain’s responses to the arts. I believe we are just on the cusp of understanding the full potential of the arts to improve brain health. Our lab brings together an interdisciplinary group of researchers, practitioners and funders to figure out how to best apply this knowledge.

Our main goal is to accelerate the development and availability of arts-based solutions to improve our health, well-being and learning. Art and design have been used as healing tools since the beginning of humankind. Research is really just catching up and providing the why. This is important, because when we understand the underlying brain mechanisms, effective dosages and other important variables, we can create better ways to treat people and figure out the best path to make these treatments widely available. Imagine your doctor giving you a prescription for dance to ease depression or painting lessons to increase your focus and attention.

There are a few examples of how art is helping us heal today. Dance, music, singing and even playing guitar has shown to benefit people with Parkinson's disease in the areas of cognition, mobility and quality of life. Some urgent care, chemotherapy suites and surgical and recovery units are now using scent to reduce stress and nausea for patients and families. Art therapists and artists employ the visual arts, including mask-making, for people with Traumatic Brain Injury. This type of intervention allows patients to access the speech-language pathway in the Broca region of the brain that can be damaged by traumatic events including war, child abuse and sexual assault. By using visual arts and symbology, these patients can give voice to their experiences and emotions.

Art is mobile, inexpensive and most importantly joyful. These characteristics make it a valuable partner in health prevention and intervention. Architecture and design has been used to improve health and well-being outcomes, too. Many hospitals are employing color to help visitors find their way around more easily and reduce stress and anxiety amongst patients and families alike. In Baltimore, MD, Kennedy Krieger Institute is designing a patient room using personalized sensory stimuli to care for children with disorders of consciousness.

Biophilia, or the use of plants and greenery, is being incorporated into healthcare settings, including emergency and waiting rooms, to provide comfort and relaxation to visitors. Research shows exposure to plants reduces cortisol levels, the hormone responsible for stress. Schools are designing classrooms incorporating more natural light, movable furniture for small group and individual experiences and mood-enhancing color rooms to reduce student stress levels.

And, at work, human resource leaders are examining the research behind burnout and workplace fatigue that can result in mental health issues, and collaborating with architects and designers to develop a range of preventative solutions. These include adjustments to lighting, adding music and scent as options, providing easy access to nature and even creating "chill-out" spaces to take a break and renew.

A Space for Being is on view at Spazio Maiocchi for Salone del Mobile in Milan, Italy, April 9 through April 14, 2019.

A private panel discussion entitled Feeling Design: Neuroaesthetics and the Impact of Design on Our Biology will also be held at the venue with Phaidon’s Editor-at-Large and Town & Country Contributing Editor, Spencer Bailey, moderating the discussion. Participants include: