Chase Hall’s practice is situated in a long tradition of autodidacts. Hall, who didn’t attend college, taught himself to paint ten years ago by sneaking into the facilities at Parsons while his partner was studying painting and sculpture there. Even now, his pictures retain a feeling that they were reverse engineered, perhaps improvised, out of necessity and sheer will. Hall’s kinship with the group of artists often and inappropriately dubbed “outsiders”—among them William Hawkins, Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial and Purvis Young—goes beyond that they were all self-trained; Hall also engages deeply with their towering contributions to the history of figuration, situating their stylistic inventions as a jumping off point from which his own paintings explode into being. Unlike many figurative painters, Hall—perhaps because of his robust photography practice—is actually able to realize the task of portraiture, in that his pictures seem to communicate the emotional innards of the people they depict.

In the past year of heartbreaking historical rupture, some of these pictures have proved unfortunately vatic; Black Birderers Association (2020) and Running From Yesterday’s Acquittal (2019) uncannily presage Central Park birder Christian Cooper’s racist encounter with Amy Cooper and the brutal lynching of 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging on a public road in Glynn County, Georgia—a phenomenon whose supernatural bizarreness gestures at how deep and long these histories of violence run, and how the trauma they produce is passed between generations.

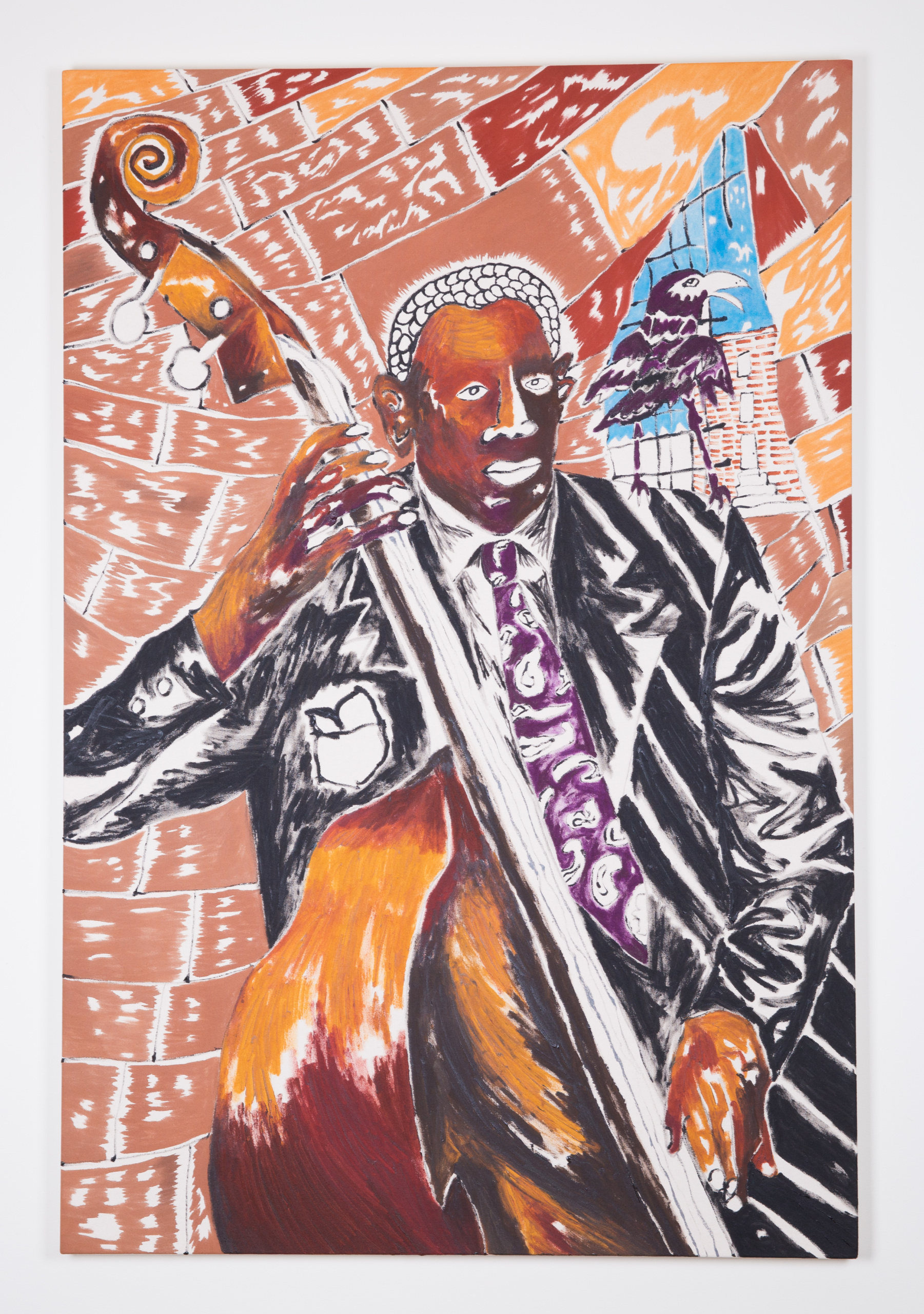

In Hall’s flourishing visual world, images of fisherman, divers, horse jockeys and jazz men are structured against stretches of stark, raw cotton canvas, a strategy he uses to engage with the crop’s foundational role in the history of race. In his sculptures, cotton appears in other forms; in Fishing with Dad (2018), two cast cement figures, one smaller than the other, sit on a stack of blue police barricades, devotionally clutching dried sprigs of the plant, the white clots of fiber dangling like lures on outstretched fishing poles. When we speak, the artist, who otherwise lives in New York, has just begun a residency at Mass MoCA, where he plans to create work for his upcoming exhibition at CLEARING gallery in Brooklyn this spring.

in your life?

in your life?