On any given day, if you enter the offices of Gehry Partners, you are likely to be greeted by Frank himself. He immediately escorts you to his wife for a friendly hello. Gentle and welcoming, Berta is a partner and backbone of the firm; she has handled the finances for 43 years. Meaghan Lloyd, Frank’s Chief of Staff and also a partner, is always by his side. Anyone who works with Frank knows you have to earn Berta’s and Meaghan’s respect first. As you glance into the open space, busy with architects and designers, you will probably find Frank’s son Sam at his desk. Frank will go on with enthusiasm about the models and designs—what Sam is working on; how he is incorporating his elder son and artist Alejandro’s illustrations and paintings into his latest projects. It’s intimate. It’s a family.

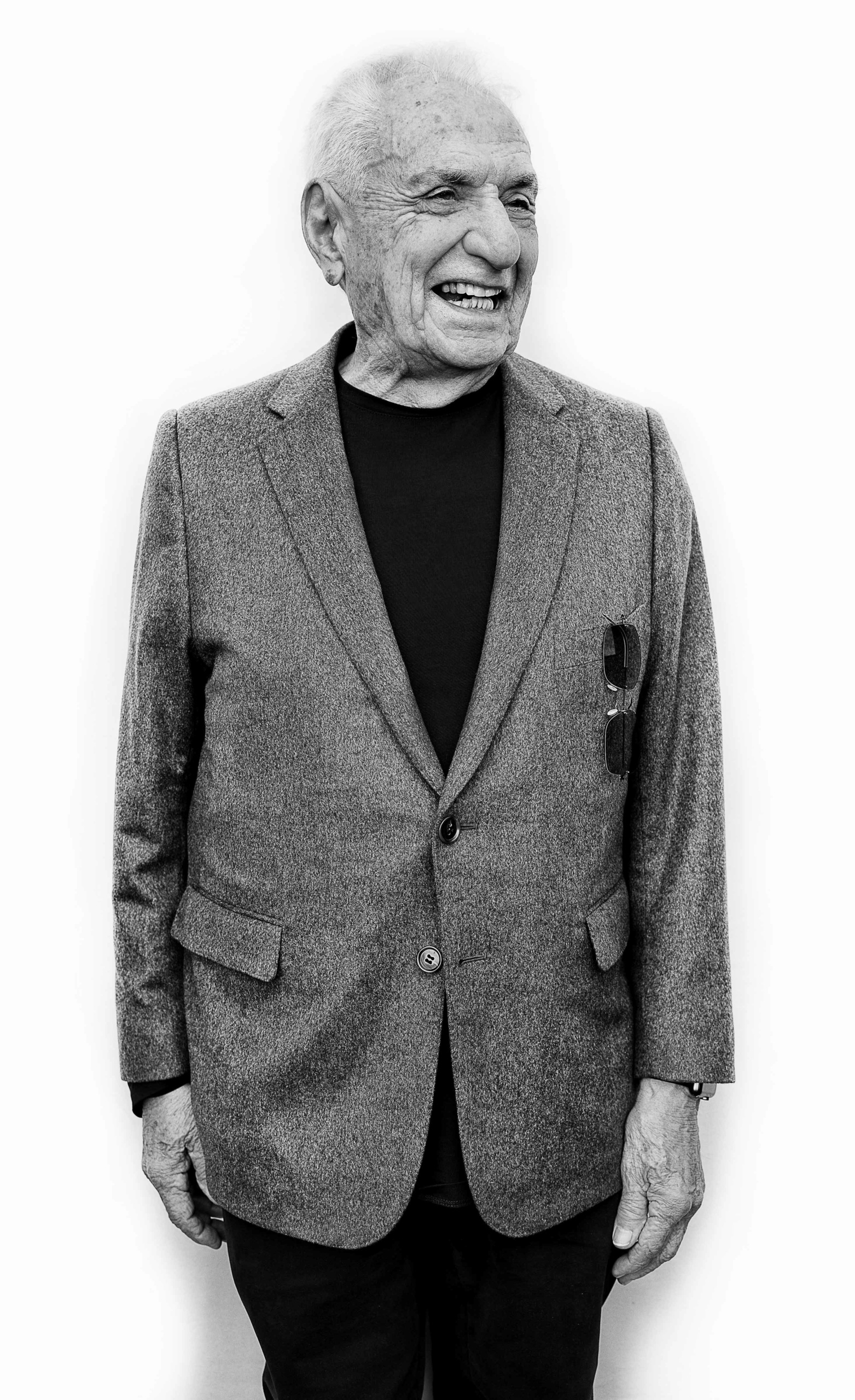

In the presence of this world-renowned architect, you cannot help but try to fully consume everything that makes him who he is: his family, his creative surroundings, his insatiable curiosity. Frank is always driving the conversation to more intellectual levels, deepening the relationship and making your time more meaningful. I often find myself simply observing and listening, forever a student of the class of Frank Gehry.

I first became aware of Frank’s work when I was studying fashion and design in college. I was drawn to his sculptural buildings of unexpected curves and in awe of his ability to break the boundaries of traditional architecture. I distinctly recall being mesmerized by Frank’s El Peix, the 52-meter-long golden fish he created on Barcelona’s seafront for the 1992 Olympic Games. Little did I know then that years later we would not only become friends, but co-conspirators in helping to make Los Angeles and the world a better place.

Frank is known for his many revolutionary global projects, including the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Museum of Pop Culture (formerly Experience Music Project) in Seattle and the Opus Hong Kong residential high-rise. His impact here, on his hometown, is just as striking. With the energy and wit of a recent college grad, he continues to transform the blueprint of LA with spectacularly innovative landmarks—from the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Binoculars Building to his Santa Monica residence and the much-anticipated mixed-use complex The Grand.

Frank’s boundless imagination and constant evolution are signatures of all of his designs and have inspired our recent professional partnership. As Global Creative Director of Wolfgang Puck Worldwide, I identify and choose the architects and designers that will best take our company into the future. My husband and business partner, Wolfgang, and I are honored to have Frank lead the team on our latest endeavor: reimagining the old Gladstones location on Pacific Coast Highway.

In addition to his commercial and residential work, Frank also makes a meaningful difference by donating his time and talents to socially-driven causes. Whether it’s his plan to revitalize the LA River and its surrounding areas or his involvement with Turnaround Arts: California, a nonprofit he cofounded with activist Malissa Shriver that brings arts education to the state’s highest-need schools, Frank understands that when you give a space new life, you give the entire community new life.

I witnessed Frank’s commitment to this philosophy firsthand when I approached him about a project involving the Children’s Institute Inc. (CII), which offers services and annual support to 26,000 children and families facing adversity and poverty. As a trustee of CII, I had a vision for an epicenter of the organization, which could only be brought to life by Frank: a campus based in Watts that would house counseling, childcare, parenting workshops, art classes and other programs all under one roof. I knew the influence and power of having a Gehry Partners-designed building in Watts would have the potential to transform the entire neighborhood. The conversation with Frank had barely begun before he said, “Yes.”

Along with his son and lead designer, Sam, Frank has dedicated himself fully and tirelessly to this project. Since the design unveiling, we are well on our way to raising the $25 million needed funds, and we plan to break ground at the corner of East 102nd Street and Success Avenue this January. Frank’s passion for and dedication to this pro bono endeavor—just as with all his philanthropic efforts—is equal to that which he puts into any of his multi-million and billion-dollar commercial projects.

Frank is a model of kindness and generosity. He is also a visionary. His designs tell a story of what is to come. I feel fortunate to see the future through his eyes—and to continue to learn from him.

Gelila Assefa Puck: Did you always want to be an architect?

Frank Gehry: I’d never thought of being an architect when I was a kid. I was interested in science, literature, jazz and classical music through high school. One of my cousins, whom I looked up to, was a chemical engineer, so I thought maybe I’d want to do that. Eventually I realized I had no place in that provision. Around the same time, my family was going through hard times, financially. We ended up in LA, and I became a truck driver, going to night school at LA City College.

GAP: So what led you to the career you have now?

FG: In college, I took a class in ceramics at USC night school and met an incredible teacher named Glen Lukens. It was his actions, introducing me to the field of architecture and getting me to enroll in a night class at USC, that got me to the place where I am now. I even think he paid for my tuition, which was way over my head. From then on, architecture was it. I got married. My wife worked, and I studied and worked on the side. Between us, we were able to handle some of the tuition, and in my last year, I got a scholarship.

GAP: Today, your style and buildings are admired worldwide. How do you personally describe your architectural aesthetic?

FG: I don’t really know how to describe my work except that it’s intuitive, and I trust my intuition. It’s about curiosity, searching and looking at the world around me. At the beginning of my career, LA was full of warehouses and industrial buildings. There was a kind of tough aesthetic. Artists like Rauschenberg, Don Judd and Bob Smithson were using materials from the industrial communities to make their work. All those people were supportive, so I took off in that direction.

GAP: What is your approach to design?

FG: Over the years, we have thought about how best to express architecture in our time, and it certainly was not the glass boxes of postwar called modernism, which seemed cold and spooky. There was a need for humanism, something to warm the hearts. Some of my brethren went back to historic references and created a world of postmodernism. I never felt it was negative, except that I wondered why we couldn’t find our own way to humanize architecture other than copying history.

GAP: Is that why you often use fragmentation in your buildings?

FG: I think making buildings all of one material is a bit imperialistic, in the way it has been done. Fracturing or breaking down the scale without resorting to decoration seemed like a reasonable direction to pursue.

GAP: Has your approach to design evolved?

FG: My process over the years has changed with the variety of opportunities that we’ve been given. The aesthetic for the house on 22nd Street was based on a very low budget of $50,000. It was personal, and it was the best I could do at that time. I loved the idea of talking to the existing house and making it part of the new architecture since I couldn’t afford to tear it down and rebuild it. With more public buildings—certainly museums—we were able to make gestures towards the context but also to create buildings that had feelings, form and inspiration and that functioned well. My feeling is public buildings have to have a point of view to establish a presence in the city. It’s not just decoration for decoration’s sake; it has a serious, public, emotional and financial impact on the communities when it’s done right.

GAP: Where do you find inspiration?

FG: Everywhere I look—in nature, in art, in my contemporaries. I listen to critics, clients, people in my office, my family. I find inspiration from the arts of the past, like the Renaissance, and from understanding that Bernini was discovering as he worked with his hands in clay, as did Michelangelo and many of the great artists of the world who ultimately became architects. The profession was thought of as a high art at that time. Post-World War II, architecture lost a lot of that luster and that position. Maybe our new generation is recapturing it, finally. One of the contemporary buildings that most inspired me is Ronchamp by Le Corbusier. Every time I go there, it makes me cry. It’s exquisite.

GAP: How has LA shaped you and your career?

FG: Los Angeles was foisted on me. I didn’t intend to come here. It was circumstance. Slowly, you start to understand and appreciate what’s around you and work with what you’ve got. As part of the working class, I enjoyed my life here, bringing up a family and being able to survive in the field I chose. The film business is so powerful a force in LA—it’s why everybody comes here and what everybody looks for, so it creates a cover for allowing creativity of a different kind to happen under the radar. It turned out to be a really positive thing for a lot of us because we were able to develop. I remember when the architectural critic Reyner Banham, who wrote Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, asked about a house I had done on Melrose. I said, “This is my first building. Please, don’t publish it. Don’t talk to me about it. I’m not ready for primetime; I’m just starting.” I put him off, and he wrote about it anyway. A couple years later, I met him and apologized for my insecurities, but I think it was the right thing for me. For buildings in their early stages, it’s nice to be under the radar without everybody commenting. Let’s just work at it, make it and get it done. If it’s worthy, you can talk about it later.

GAP: I am so grateful to you for the work we are doing with the Children’s Institute.

FG: Children’s Institute—how could one not become involved? It’s the heart of the city where the Watts riots took place. It’s a project trying to help children who have been left out due to circumstances and who are living in fear of their futures. The Children’s Institute counsels families and children in need and has been doing exemplary work. When you asked me to design their new facility in Watts, we just had to do it for them.

This story originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of LALA Magazine