The characters that fill Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee find ecstasy in stirring their bodies before the Lord. Breathe in, scream out. Hands shake, torsos thrash. The film, released in December, reimagines the “true legend” of the deified leader of the Shakers (played by Amanda Seyfried)—a radical religious sect whose rapturous dancing earned them their name in the 18th century. The community is famously celibate: Today, it counts just three members.

Fastvold shot the film mere moments after she wrapped her work on The Brutalist with director Brady Corbet, her husband and writing partner. The duo wrote the two projects back-to-back. They then flew to Hungary with their crew and shot The Brutalist with Corbet at the helm, before quickly reorienting the team to film The Testament of Ann Lee with Fastvold in position. “You’re a little nervous,” Fastvold, who turns 45 in March, recalls of the whiplash-inducing process. “Because we might not be able to pull it off.” But, of course, they did: The Brutalist earned three Academy Awards (including one for actor Adrien Brody) and seven additional nominations, while Ann Lee was up for the Golden Lion and a Golden Globe, among other nods.

After cutting her teeth acting in her native Norway and the U.S. (both Fastvold and Corbet were child actors), Fastvold flexed her muscles as a director with two intimate features: 2014’s The Sleepwalker and 2020’s The World to Come. In contrast, Ann Lee bursts with both movement and flair as characters flit across the screen, periodically arranging themselves into painterly compositions. On the heels of what may well be the most pivotal two years of their careers, Fastvold and Corbet sat down for a conversation that spins almost as wildly as the Shakers themselves, covering everything from spiders to soap operas.

Mona Fastvold: How are we going to do this? We have no time to actually catch up. I don’t know how we’re going to keep this conversation on track.

Brady Corbet: Can you tell everyone how you first became interested in the Shakers?

Fastvold: We were both always interested in the design aspect. I was looking for a hymn for The World to Come, and I had this idea that [the characters] would be singing this song while doing the laundry. I came across “Pretty Mother’s Home,” and discovered it was written by a freed slave [and member of the community for 51 years], Patsy Roberts Williamson. That led me down the rabbit hole of the Shakers.

Corbet: Describe your earliest relationship to faith, religion, and spirituality.

Fastvold: I wasn’t raised religious at all. My parents are not religious. Kind of spiritual. There was some astrology, tarot cards, stuff like that.

Corbet: Is that spiritual or mystical? They’re mystical atheists, which makes perfect sense.

Fastvold: Totally. My grandmother would take me to church sometimes when I was little. Beyond that, I didn’t have much of a relationship with religion, though it always fascinated me. I would seek it out. I would go to my best friend’s Catholic Mass voluntarily because I loved the choir and the incense and the feeling of that room. It was so beautiful. I remember going to synagogue for the first time and having a really interesting conversation with the rabbi there. I was always seeking it out, but I could never join.

In the film, the only religious aspect that I could connect to myself was a devotion to work, or to art, or to the work one does as an artist. It’s mysterious at times to me. Why devote yourself so completely to something that doesn’t necessarily serve a concrete purpose?

Corbet: Part of the reason I thought that you were so uniquely poised to make this movie is because of your background in dance. Can you speak about your time in Denmark?

Fastvold: I was a child actor in Norway and worked in television. I was also a dancer for many years. I went on to study at a school in Møn outside of Copenhagen [Folkehøgskolen Møn]. We had an assignment where we were supposed to make examples of boundary-pushing performance art that was particularly popular in the ’60s and ’70s. Nudity and painting in pig’s blood, things like that. I chose my immense fear of spiders as the center of that assignment.

There was a boy at school who loved spiders, captured them all day. I got him involved, I invited the whole town in, and I bought them beers. I asked them to cheer me on, to yell at me, “Do it, do it, touch them, open up the jars.” I placed all the spiders in my hair and my body. After that, I was cured—exposure therapy. I thought about that when I was thinking about Ann Lee. Those moments—where they’re confessing their sins with everyone gathered around them, cheering them on, letting them scream and shout and shake—how cathartic, how powerful that experience must be.

Corbet: You were only in Denmark for a year?

Fastvold: Yes. Then I went back to Norway to do a year on a soap opera.

Corbet: Would you like to elaborate on your year acting in a soap opera?

Fastvold: No, but it paid for a lot of my time here in New York, so it was good.

Corbet: I worked on a lot of trash, but I never did a soap opera.

Fastvold: You’ve done a sitcom, though, haven’t you?

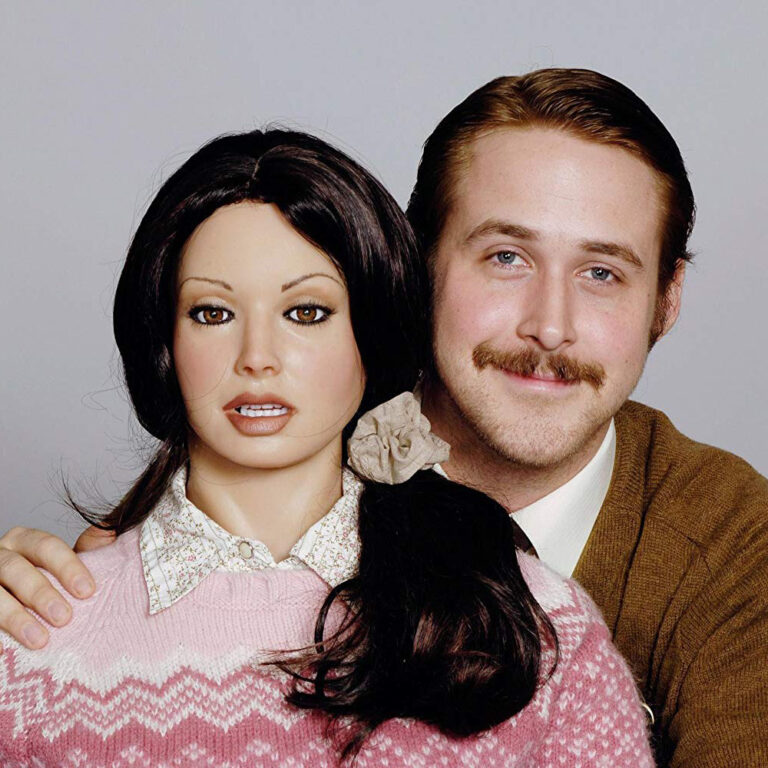

Corbet: Yes, but I was 7. I don’t really remember. [Laughs] Regarding Amanda [Seyfried], you’ve known her for longer than you’ve known me, actually.

Fastvold: Yes, we go way back. When we were directing her on [the Apple TV series The Crowded Room in 2023], we just realized how versatile she is as a performer and how much dramatic depth she has. A lot of people see Amanda and immediately think of Mean Girls, Jennifer’s Body, or Mamma Mia! It was you who said that we should just send her this script. We wrote her like, “How are you with accents?” She was like, “I’m great.”

Corbet: [Laughs] Sounds like Amanda.

Fastvold: Later, she was like, “I’m terrified of this Mancunian accent, but I’ll do it.”

Corbet: It’s a really challenging accent. Could you talk about how the rest of the cast came together? I wasn’t very involved with that process. I’m trying to think of things that I don’t already know the answers to.

Fastvold: We invited Christopher Abbott and Hailey Benton Gates over for dinner and asked them to read the whole script out loud to us. Because we had so many bits and pieces that were musical and movement-based, it was really important to hear it out loud. Lewis [Pullman’s] character [William, Ann Lee’s brother] was the hardest. I think it was a scary role. It’s always scary to do all that amount of movement and dance if that’s not your background. He had this beautiful balance of feeling really confident and very pathetic and insecure at the same time. There was this duality in him that I just loved, and I thought was so right for the role of William. He’s the drummer in his band, Atta Boy. He hadn’t sung before, but he was definitely musical.

Corbet: His mother was a dancer.

Fastvold: She started working with him right away. They started practicing together. Our choreographer, Celia Rowlson-Hall, and I met almost two decades ago on Gossip Girl.

Corbet: I like that you just tried to slide that in. It was in what year?

Fastvold: A really fucking long time ago. We were featured extras—as models. That’s how long ago it was. We became friends immediately because of our love of modern dance and music, and started collaborating. When I first had the idea of working on this film, I told Celia about it. I could see her choreography in the film. She comes from a background of faith. I knew that she would have a way into doing movement that could really portray deep faith, but in a respectful way—that she could find a really truthful way to access that movement of worship and ecstasy.

Do you want to talk about our writing process?

Corbet: Sure, you can start asking me questions.

Fastvold: People usually ask us this—if we know who is going to direct the film when we’re writing it—and we always do. The project always originated with one of us, and that’s the person who’s directing it. Knowing that I’m writing for your voice and imagining how you’re going to shoot it is helpful. Same when you’re writing with me. It usually starts with many long conversations. I remember Celia said recently, “You talked to me about this project a decade ago.” That’s usually how long it takes to find the path in.

Corbet: Mostly, we talk about a project for a few years, and then when we finally sit down, we execute it—historically—pretty quickly. Are you just going to interview me for the rest of the time?

Fastvold: It’s much more fun for me. Do I direct differently from you, do you think?

Corbet: Yes, but I don’t think that I could distill it into any one detail. I don’t get how people co-direct projects because your mind’s eye, the decision to shoot over the right shoulder or the left shoulder—

Fastvold: It’s just all intuitive.

Corbet: Absolutely. That continuity of vision is the most important aspect of the job. It’s not that I think any one person is better-suited to call all the shots; it’s just that if all 150 collaborators were calling the shots, then they’d pull the whole thing apart.

Fastvold: [Going from your film to mine], it was such an intense period because we wrote The Brutalist, then we wrote The Testament of Ann Lee. We were getting through Covid, jumping into the production of The Brutalist, which was a beast. Then immediately, while in post-production, jumping into full gear on Ann Lee. There was really no break. I remember Daniel [Blumberg, the composer] had one day off before finishing the score on The Brutalist, and then starting with Ann Lee. I don’t think I had time to metabolize or to absorb any of the things that we learned.

Corbet: It was one long production.

Fastvold: Both films were shot in Hungary. There was a lot of crew there who just stayed. We had the trust of everybody. There were a lot of situations in The Brutalist where I think some of the crew were like, “You’re not going to be able to pull this off.” Really challenging days, just packed with so much text and then complicated, long sequences shot with tons of extras. We figured it out. Everyone had just watched us do that.

So I came into my film with a wonderful sense of confidence, which is important when you have days on your schedule that, even just on paper, seem impossible. The only way to make the film is by having those days—you just do the best you can with them. It’s a muscle. The more you get to be on set, the more confident you feel when you’re working.

Hair by Sydney Valentine

Makeup by Yasuko Shapiro

Production by Leah Oliveria

Styling Assistance by Kat Cook

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Tessa Thompson Took Two Years Out of the Spotlight. This Winter, She’s Back With a Vengeance.

On the Ground at Art Basel Qatar: 84 Booths, a Sprinkle of Sales, and One Place to Drink

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?