If the Winter Olympic torchbearers are any indication, 2026 is the year of male yearning—specifically queer male yearning. Smutty, shirtless men are all over our screens and our bookshelves from Heated Rivalry to season four of Bridgerton and the kinky gay biker film Pillion. It’s been a long time coming. In 2023, Circana BookScan, which tracks book sales across the country, found that LGBT fiction purchases were at an all-time high, over 6.1 million books moved within the year, and there was a 173 percent surge since pre-pandemic levels. Whether they’re facing off on the ice or clinging to each other on motorcycles, the pattern is clear: We can’t get enough stories about wanting—especially when that wanting is delayed, misread, and, well, sexy.

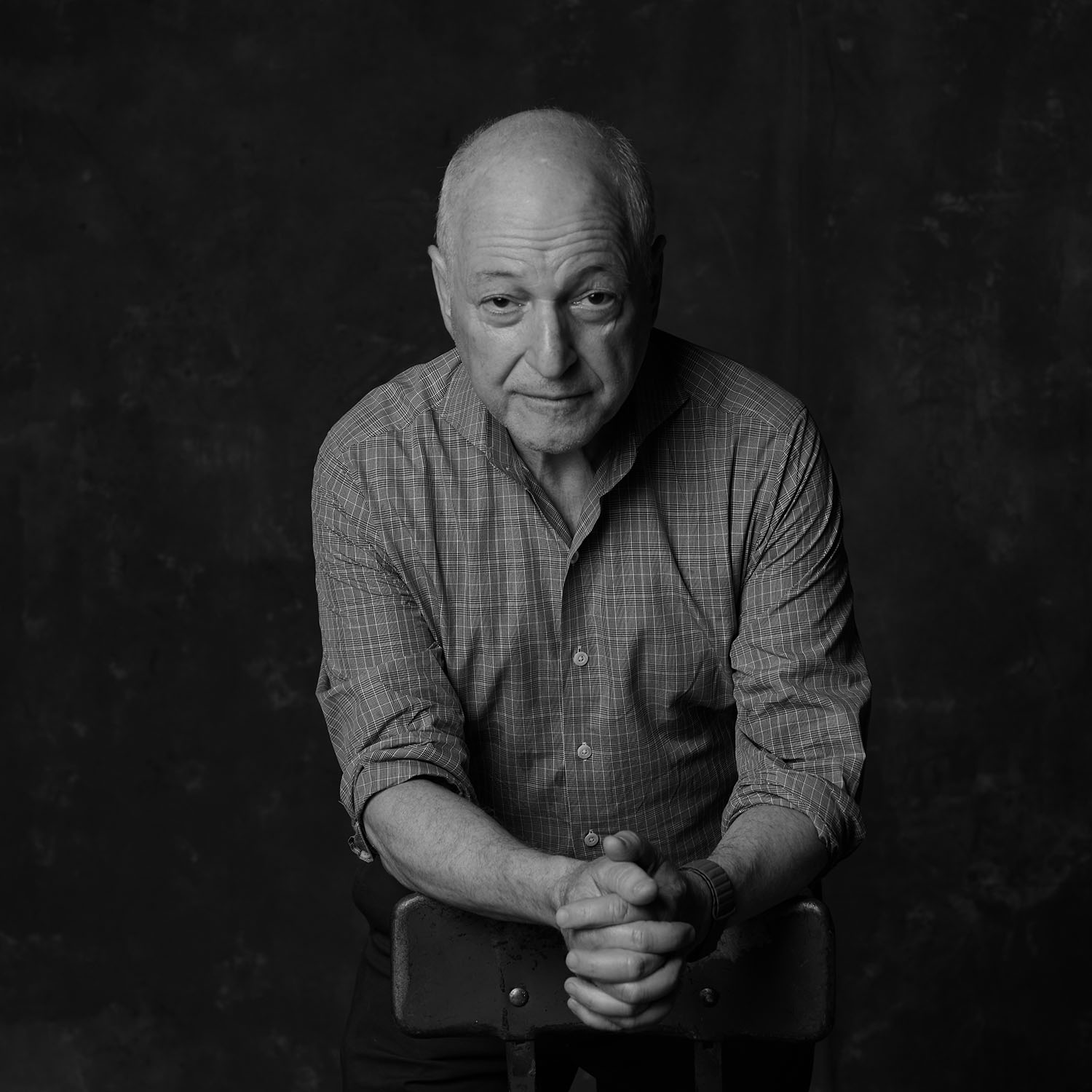

With MLM romance taking over, it feels appropriate to turn to the writers who paved the way—and to André Aciman, whose work has long defined the modern queer romance canon. The author of Call Me by Your Name and last year’s Room on the Sea understands hesitation and desire—and their power—both personally and in literature. Who better to get queer love story book recommendations from than Aciman himself? The writer and professor of comparative literature at CUNY’s graduate center shares the classic novels he keeps coming back to, his favorite teacher/student romance, and why Wuthering Heights will always be famous.

What book should someone read if they want to get to know you?

First of all, it is doubtful that they want to get to know me, but whatever. Let us say that there are many books that I have read. This is all I’ve done in my life, really—either read books or attempted to write them. And most of my life was spent trying to read them. I like novels that have to deal with hesitation. Not the characters who go and move and do things, but those who reflect and sometimes are impeded from doing anything because they’re reflecting too much.

That has been my credo—or, if you want, my inhibition. I am, by nature, a very shy, inhibited human being. So that makes me who I am. The author of a book like Call Me by Your Name is, in fact, a very inhibited, deferential, timid, hesitant human being who is reluctant to engage with anything because he’s going to change his mind the next day. And that has been my forte. That is my signature on everything.

If I had to pick one author who influenced me a great deal—and who represents many facets of my personality—it would be Marcel Proust. Everybody knows this because I’ve been talking about him ad infinitum, and enough is enough. I teach a course on him. Essentially everything he does is wrong, or he’s bungling, or he’s facing difficulties he never foresaw. And he loves his mommy—which is not exactly a strong point. I loved my mommy, but not as much as he did. But: hesitation, deference, a desire to put obstacles because you’re afraid of what action does—that is me. That is definitely me. And that’s why I created a character like Elio, because he is exactly like me. A character like Oliver is the exact opposite of who I am.

Do you think that tension between opposites is at the heart of romance for you?

Put it this way: the relationships I’ve had in my life, I don’t remember them. Those that I never had and wished I had—those are still with me 40, 50 years later. They continue to nag me because I haven’t done something I should have done decades ago, and I was never able to—or I was afraid to—whatever the reason. In essence, I am a person who goes after people. But those I have never been bold enough to go after remain forever on my list of things that I should have done. So I am both: the person who does things, and the person who hesitates and fears and deliberates far too much.

What’s a book you turn to when you’re looking for inspiration—both in your writing and in life?

I am a re-reader. There are books I’ve re-read many times. One is Wuthering Heights. Another is Crime and Punishment, which influenced me significantly. I thought human beings were one way: either you accomplish things and aim for things, or you bungle and do nothing. Then Dostoevsky proved to me—thank God I discovered him early; I was 14—that you are both: shy, spiteful, cruel, envious, and also extremely kind and deferential. At the same time, you hate people because you don’t want to like them. This confluence of contradictions—I said, “Oh my God, that’s me. I don’t have to be one way or the other. I can be everything.”

It’s interesting you bring up Wuthering Heights since it’s been adapted into a film—people are re-engaging with the text. I think right now there’s broader interest in romance, historic and contemporary.

With Wuthering Heights, every few years it seems there’s a new movie. Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, and Henry James: These are novels that keep coming back. These are stories that don’t disappear. I don’t approve of all the movies—some are trashy and misinterpret—but that’s fine. The fact is that we want them.

Was there a particularly formative book for your ideas about desire and sensuality?

Yes. I’ll give you an example of one that nobody reads because it disappeared: It’s called Olivia. I wrote a preface for it because I couldn’t stand that Penguin—who published it initially—made it disappear, so they reissued it. Olivia is a novel about the love between a woman and a girl. It’s extremely powerful. Of course, it aroused me in many ways—but it couldn’t arouse me because it wasn’t exactly sexual. Still, it got into me, and I never let it go. In fact, a lot of Call Me by Your Name is attributable to Olivia. The author was Dorothy Bussy—she wrote it under a pen name at first—but it’s a small, short novel that should have been very famous and never was.

What was it about that book that resonated with you?

It’s the fact that this girl wants to sleep with her teacher, and the teacher says, “This is wrong. I know what you want. I want it too. But we cannot do that.” That kind of language means it’s put on hold forever. And I love that. I used it—copied it, pilfered it—in Call Me by Your Name because I love the fact that somebody tells you, “This is wrong. We both want it, but we cannot.” The fact that it gets said—and understood—and cannot go through is an amazing moment in life.

That’s something it shares with Wuthering Heights: transgression. With a lot of queer literature, it’s often about repressed desire and yearning. When it comes to queer literature, what do you see as the through lines? What qualities unite that canon?

It’s not limited to queer literature. Most of us are inhibited. We can be free: We take all kinds of drugs and drinks, whatever—and that frees us for a while. But in essence, we are repressed human beings.

With gay literature, it tends to have two ways to go: one, somebody gets killed—which is awful. Or two, they decide to live together and become domestic. I like to say: I don’t like to write about people who, on Sunday afternoons, do the laundry and fold the sheets. I don’t want to go there. I would much rather stay with “let’s have sex.” I’m much more interested in: What did he mean when he said this? Did I mistake it? There’s always innuendo, and I love innuendo. That’s my forte.

What can reading—romantic literature, specifically—do for us when we’re working out these feelings?

It does two things. It teaches you what other people have done—and you might want to do it. It outlines possibilities. And it also allows you to investigate what it is that you want, what you understand, what you thought you understood. Many of the people who loved Call Me by Your Name did not love it because it reflected exactly what they experienced. They loved it because it reflected what they wanted—what they hoped they might encounter in life.

You live it, you borrow their lust and their love, and at the same time it’s safe. It’s nice to feel that something given to you on paper or on screen is something you want in your own life. Are you going to find it in real life? That’s another question.

Are there any underrated novelists you wish more people read?

There are many great novels. For example, a book like Oblomov [by Ivan Goncharov]. Nobody reads it unless you’re a Russian major, or you’re wide-ranging and want to explore. It’s about a character who is timid and lazy, and it goes on for hundreds of pages. He’s constantly wrong about everything, yet you feel sorry for him. I’ve read it three times, and three times I’ve cried. It’s the saddest book I’ve ever read. You tell yourself, “This time I’m not going to cry.” But you still cry.

And many British actors who retire—they tend to write very well. Dirk Bogarde, for example, wrote beautiful novels. Alec Guinness—beautiful writing. And Alan Hollinghurst is a fantastic writer.

Who deserves a biography or a novel about them that doesn’t have one?

A figure like Louis Armstrong. He led a complicated, rich life. You’re amazed at the number of things he could say—the scattered thoughts you think couldn’t go into a book, but they do. People assume he’s limited to trumpet-playing. He’s not. That’s what I look for.

To round out these interviews, we usually ask for four or five book recommendations—anything that reflects you, your sensibilities, and your taste.

I went and did a list of all the books I’ve read in the past three years. One: Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, who wrote The Leopard, is probably the greatest writer of Italian literature in the 20th century. There’s no question. I love his work. I also love Elsa Morante. I’m not a big fan of Elena Ferrante.

Can I ask why?

It’s not profound enough. I read two novels and the first volume of the tetralogy—that was enough. I get the idea. It’s not for me. A book I had never read because it seemed too big: Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. It is a fantastic work of art. A piece of genius. And another in the same company: Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. Another book I discovered is Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet. Somebody forced me to read it. I spent a whole month reading it. I said to myself: “Thank God I lived long enough to have read this book.”

But, my favorite book of all is The Peloponnesian War. It shows you how stupid mankind can be—and how people die in war when they shouldn’t. You’re taught a lesson. And another book I love: Robert Caro’s The Power Broker. When I’m biking—which I do in Central Park all the time—I listen to books. It’s fantastic.

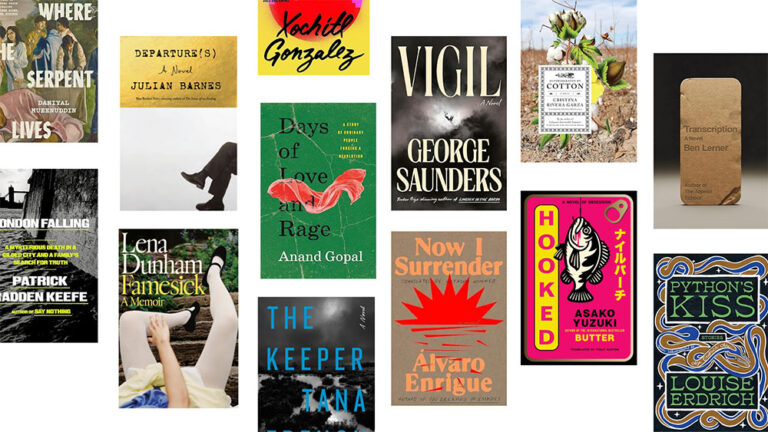

Andre Aciman’s Required Reading

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, 1847 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1866 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- Olivia by Dorothy Bussy, 1949 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- Oblomov by Ivan Goncharov, 1859 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, 1958 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa, 1982 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, late 5th century BC (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

- The Power Broker by Robert Caro, 1974 (Amazon, Barnes & Noble)

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?