A man is hung twofold in the first scenes of Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights. The criminal dangles from a scaffold for the entertainment of a jeering crowd, but he’s also hung in the colloquial sense—his post-mortem erection on full display. Swinging lifelessly from the Yorkshire gallows, the hanged man’s hard-on forecasts the equal parts arousing and grotesque Emily Brontë adaptation ahead. The message of Fennell’s latest cinematic release is clear enough: sex and death this way comes.

Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, published in 1847, sits firmly in the category I like to call “Literature People Have Opinions About.” Most of us encountered the novel too young, studied it too closely, or quietly built parts of our personality around misunderstanding Heathcliff. Longing is a powerful developmental force, and his brusque, tortured unattainability functioned as a sort of gateway fixation: the object upon which generations of us have projected our romantic masochism, the embodiment of the “I could fix him” mentality (Brontë wrote the novel in her late 20s) that eats years of our youth before we learn to date someone who likes us back.

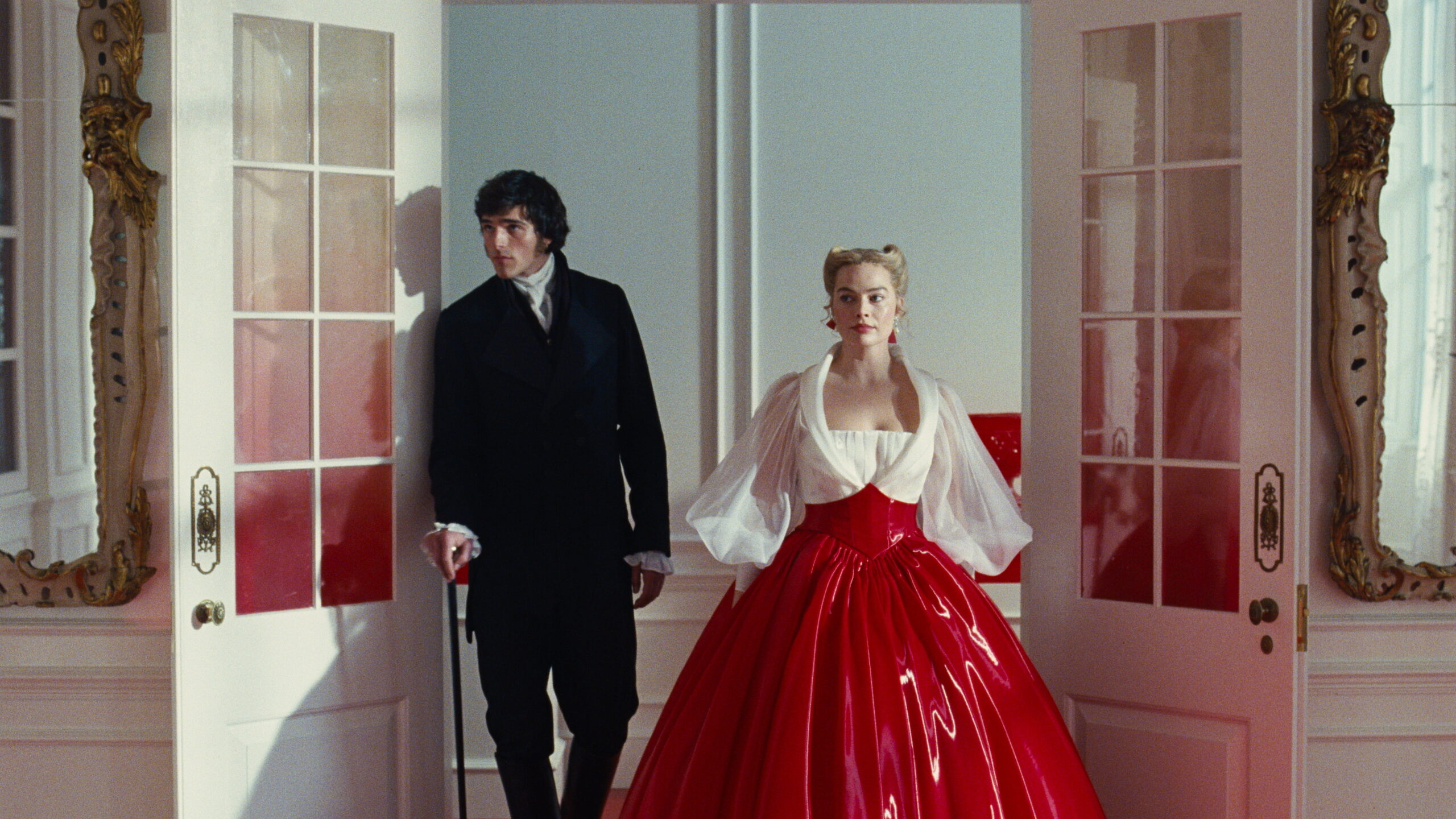

The film’s first act—the mud-spattered foreplay, if you will—is inarguably horny. Not in a lurid way, but in that heightened register where everyone looks gritty and half-starved. Out on the windy moors, Margot Robbie’s precocious Catherine and Jacob Elordi’s strapping (very strapping) Heathcliff stare into the middle-distance, emotional ruin hovering politely in the background. Their burgeoning sexualities manifest first through voyeurism—Cathy and Peep-cliff secretly look on as two farmhands use horse reins in a little bondage tryst. While she (understandably) fancies her hot surrogate brother—side-burns and all—Catherine is torn between crazy, stupid (though not technically incestuous) love and the pleasant alternative of Edgar Linton, a more conventional suitor from the neighboring moor. At numerous points, the tension becomes too much to bear: early on, Heathcliff catches Catherine, awash in hormones, masturbating against a rock, which I don’t remember from the book.

Brontë—who was raised on the rugged Yorkshire moors herself, and whose own brother’s destructive, opium-fueled decline is believed to have provided the template for Heathcliff’s behavior—understood that physical wounds heal, but psychological scars linger. Fennell’s rock wank, by contrast, carries us far beyond the heaving subtext and creeping heartache of the source material and toward something a good deal spicier than the whey-and-water gruel on Catherine’s dinner table. The true depravity of Brontë’s novel lies outside the sexual: It’s about people choosing misery with terrifying conviction, love metastasizing into vengeance, pride calcifying into lifelong torment. But subtlety has never been Fennell’s chosen instrument—moor-side masturbation feels less like an effort toward character development and more like her directorial signature. You have to ask yourself: Is it an Emerald Fennell project if someone isn’t being sexually weird when they think nobody’s looking?

Of course, adaptions are slippery suckers. Stay too close to the source, and you’re accused of complacency; stray too far, and people tweet “sacrilege.” Purists are never satisfied because satisfaction isn’t really the point: A vigilant safeguarding of the text is. But for a film to feel current, or even a tiny bit dangerous, it has to account for all the soft and hard porn we consume, the violence that floods our feeds every day, the rapid-fire micro-takes that substitute for genuine discourse. In all that she does, Fennell caters to these new predilections—consider the sensory assault (the grave shagging and cum slurping) of Saltburn, the extreme violence and millennial pastels of Promising Young Woman, the satin-gloved chaos and gleeful collapse of good taste that permeates her oeuvre.

Wuthering Heights’s casting, though engaging, is objectively unhinged. Watching two dialect-coached Aussies speed across Yorkshire on horseback generates a low, continuous hum of cognitive dissonance. It’s hard to suspend disbelief when Fennell’s raison d’être is to push the limit of your beliefs, to conjure moments incongruous with your expectations. All the same, to play Heathcliff (or Frankenstein’s monster, as Elordi did recently, for that matter) requires a pressurized perspective, a sense of having marinated emotionally over decades. Elordi’s Heathcliff feels more recently assembled: He delivers the iconic “be with me always, take any form, drive me mad” line with unpretentious gusto, but a deeper, life-ruining obsession feels slightly beyond his reach.

Robbie, for her part, is wonderful as Catherine—naïve and occasionally feral, her dresses billowing around her like the cellophane on a fruit basket. But even through heart-attack red costuming, the Barbie doll and Wolf of Wall Street vixens still seep out. You occasionally wonder if Robbie has wandered out of a particularly windswept couture campaign and onto Fennell’s set. In a different adaptation—one calibrated to the seriousness of the source text—our leads might have disappeared more fully into their roles. Fennell repeatedly plucks us off-moor, reminding us that, if Barbie and Elvis had existed in the same universe, they wouldn’t have wasted as much time as Catherine and Heathcliff in getting down to it.

Ultimately, I’m not convinced a film so eager to amuse modern bouches can possibly eviscerate us in the same way as the novel that birthed it. Where Fennell’s other films mined orifices and our capacity for bewildered disbelief—cavorting naked through manor houses, slurping adolescent bathwater—to achieve their maximalist sensibility, with Wuthering Heights, the director settles for scandal-lite in a heritage font. Having exhumed Brontë’s version, Fennell’s take seems to be what if all this repression were extremely cinematic? and embracing style above all else. Enthusiasts of the novel’s emotional disemboweling may not appreciate Fennell’s fantastically fun take on their somber, sacred text, but that doesn’t change the fact that sales of Brontë’s original spiked by 132 percent after the film’s first trailer was released last September, or that Fennell has nevertheless produced a slick, imminently watchable and highly entertaining rollick—even if it trips over itself now and then as it tries to make sure it’s being fun enough.

More of our favorite stories from CULTURED

Tessa Thompson Took Two Years Out of the Spotlight. This Winter, She’s Back With a Vengeance.

On the Ground at Art Basel Qatar: 84 Booths, a Sprinkle of Sales, and One Place to Drink

How to Nail Your Wellness Routine, According to American Ballet Theater Dancers

‘As Close to Art as Pop Gets’: Jarrett Earnest on Charli XCX, ‘The Moment,’ and Our Culture of Hyper-Exposure

10 of New York’s Best-Dressed Residents Offer the Ultimate Guide to Shopping Vintage in the City

Sign up for our newsletter here to get these stories direct to your inbox.

in your life?

in your life?